Blue Poles: the painting that changed Australia

The $1.4m purchase of Jackson Pollock’s masterpiece in 1973 blew the art world’s brain, blasted the reputation of the artist into a whole new stratosphere and sent a powerful message on the international telegraph.

Our cultural romanticists tend to celebrate the early 1980s as this nation’s Warholean 15 minutes of 20th-century fame, with Australia II, Paul Hogan, Olivia Newton-John and Men at Work simultaneously thrusting Australia into the international spotlight. But does Crocodile Dundee really stack up against Wake in Fright (which received a standing ovation at Cannes in 1971)? Did the America’s Cup (which we had to give back) leave anything as enduring as the sails of the Sydney Opera House, which dazzled the world when officially revealed in 1973?

Germaine Greer ignited a global gender civil war with The Female Eunuch in 1970, Evonne Goolagong beat Margaret Court in an all-Australian Wimbledon final in 1971, and Patrick White’s Eye of the Storm won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1973. Today, the embarrassing “G’day USA!” campaign of the early 80s, when compared to the cultural impact Australia had on the world a decade earlier, seems little more than a spectacular chunder of style over substance.

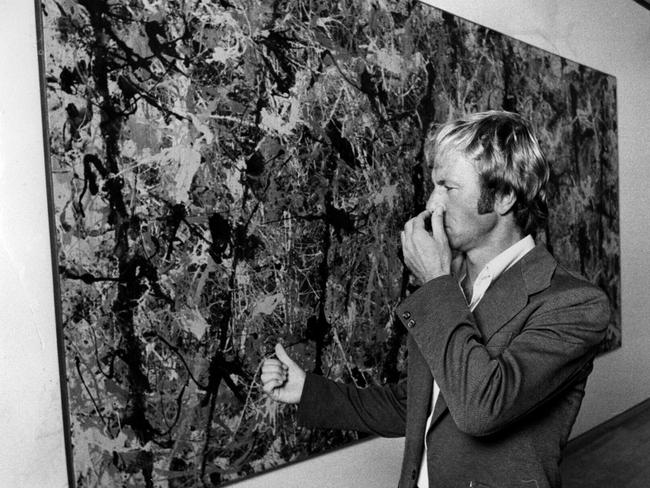

At the epicentre of our 70s boom stands Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles, purchased for the Australian National Gallery by the Whitlam government for a tear-jerking $1.4m in 1973. It was, at the time, a world-record investment in postwar American art, and the Australian media was so livid even those who were mere children at the time remember Blue Poles being something of a dirty word, along with the godless IRA and Jesus Christ Superstar (the cast and crew were all going to hell, apparently).

Today, the question as to whether the painting is any good dwells in the same vault of irrelevant mysteries as the ability of shag-pile carpet to withstand traffic and the depth and breadth of Abigail’s acting talent. The indisputable fact is that the purchase of the picture simultaneously blew the art world’s brain, blasted the reputation of the artist into a whole new stratosphere and sent a powerful message on the international telegraph: We Aussies mightn’t know much about art, but we know what we like and we know how to get it – in this case, a bit-of-the-old abstract expressionism signed by one who would soon be considered a grand master of American modern art.

Journalist Tom McIlroy couldn’t go wrong with such sexy material, so, despite being his first book, Blue Poles: Jackson Pollock, Gough Whitlam and the Painting That Changed a Nation is an engaging read and a fine testament to a moment in time that is scandalous and triumphant in equal measure. It is also just a trifle sad. There are those who suffered because of this deal, like the Hellers, the New York family who reluctantly let the painting go after decades of loving it, the empty space on the wall nothing compared to the hole in their hearts not even a big fat payday could repair.

The book begins with a dutiful biography of the artist which, while not particularly illuminating for serious students of art, does well to document the highs and lows of the car-crash alcoholic who lost his life at the wheel in 1956, knocking out the most knowable versions of himself on canvas. Though McIlroy fills 137 pages before the Australian story even begins to dawn – a decision that, at first, seems unnecessarily studious – it serves, in the end, as a reminder that great art is forged through love and pain before the chequebooks have even been flipped open.

History remembers Gough Whitlam as being the hero in the story of Australia’s relationship with Blue Poles, and it’s true we have Gough’s magnificent ego to thank for ultimately signing off on a deal others may have considered a bourgeois toss that would bring nothing but trouble at the ballot box. But, as McIlroy reveals, the hard work belonged to James Mollison, the newly-appointed curator of the ANG. Charged with the awesome task of filling the walls of a gallery whose construction was not even completed, Mollison sent “scouts around the world” for worthy potential acquisitions, one of which turned out to be a Jackson Pollock entitled Mural on Indian Red Ground, which was going for a comfortable half-million.

The acquisitions committee squabbled and erred, and Mollison lost out to another bidder (the painting was ultimately procured by the Shah of Iran).

Crazed by the near miss, Mollison became almost irresponsibly desperate for a Pollock, and the only one he could find in a private collection, and thus remotely purchasable, was Blue Poles.

It may be a surprise to some that Pollock was no household name in 1973 – just another in a clutch of American abstract expressionists, arguably less bankable than contemporaries like Willem de Kooning or Franz Kline. When New York curator William Rubin declared that “in decades to come, more people around the world would know the name Jackson Pollock than would know the name Richard Nixon”, he was laughed out of hand for what McIlroy diplomatically describes as “a bold prediction”, one that gambled Pollock might one day be up there with Warhol, Picasso and Salvador Dali.

Mollison commissioned some expert opinion, notably from Henry Geldzahler, curator at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, who declared Blue Poles “the most important postwar American painting still in private hands”. But the memo that sealed the deal was a masterstroke of reverse psychology penned by Brendon Kelson, secretary-manager at the ANG, who advised Whitlam that, whether he bought the painting or not, “the fact (Blue Poles) was offered to Australia will be recorded in the literature of the art of the mid-twentieth century”. There was no way in hell Gough was going to go down in history as an uncultured philistine rather than a Nostradamus of art, thus he forwarded the memo to his bureaucrats in consulate with a two-word addendum: “Buy it.”

The rest, as they say, is history, as they say. Recent evaluations of Blue Poles hover in the high heavens of $500m, but sucks to that – its importance to the cultural reputation of this nation cannot be measured in dollars. After Blue Poles, nobody in the world dared suggest Australia didn’t know a drip from a doodle.

We’ll never sell.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout