Blood, barbs and the Bard: love and leadership lessons from Shakespeare

Here’s one of the surprising possibilities that slithers out of an engrossing new book, Death By Shakespeare: Juliet’s fake death, the coma-like one before her dagger-inflicted real one, might have been caused by a blue-ringed octopus.

Here’s one of the surprising possibilities that slithers out of Kathryn Harkup’s engrossing new book, Death By Shakespeare: Juliet’s fake death, the coma-like one before her dagger-inflicted real one, might have been caused by a blue-ringed octopus.

As the Bard does not say what potion is in the vial Juliet drinks from, Harkup, a chemist by training who had a hit with her first book, A is for Arsenic: The Poisons of Agatha Christie, lists sedatives that would render the young lover “stiff and stark and cold”.

She considers the roots of the mandragora plant, which Shakespeare refers to in Othello and Anthony and Cleopatra, but leans to tetrodotoxin, a toxin that can be accumulated and used as a defence mechanism by creatures such as the blue-ringed octopus.

Now there’s little chance William Shakespeare ever saw the lethal cephalopod that is notorious in Australian waters, but then there’s little chance he ever visited Denmark, home of Prince Hamlet, either.

We’re told he was a good student at the grammar school in Stratford-upon-Avon. As an adult he built on this education and remained open to new ideas. Is there a chance he heard stories, perhaps from traders, about exotic animals that stored this poison, which also include the puffer fish?

Harkup thinks it’s possible.

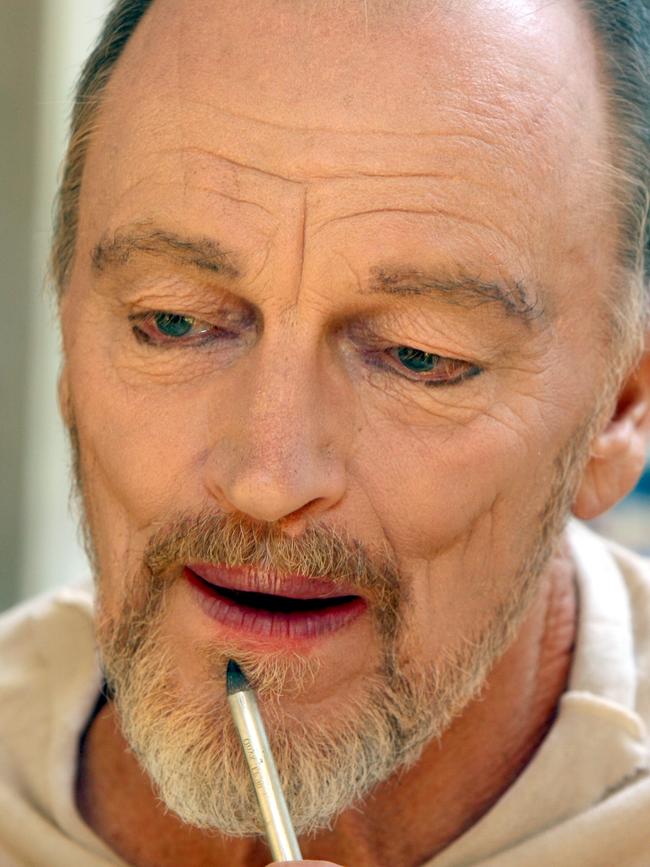

So, I’m sure, does John Bell, founder of the Bell Shakespeare Company and one of Australia’s leading interpreters of the great Elizabethan writer, who would have turned 457 last week.

“He was tremendously curious and a great researcher,’’ Bell writes in Some Achieve Greatness. “He was as fascinated by the newest science, technology and exploration and he was by history, classic art and literature.”

Bell’s book, centred on what Shakespeare can teach us about leadership, reads as though the author, who is now 80, is writing about his best friend, a bloke he has known all his life, and in a sense that is true.

“Some people say, ‘We don’t know much about Shakespeare’. On the contrary, I think we know pretty much everything about him: everything he saw, heard, thought, felt and loved.”

Just when it feels like Bell is going to reveal the size of Bill’s codpiece, he pulls back a little. “ … of course the man was an actor, a fabulist; and it’s very hard to determine when it’s Shakespeare talking and when it’s one of his characters, because they are so intimately knitted together.”

Even so, he believes the lessons on leadership — for better (Henry V, although he did kill all the French prisoners) and worse (King Lear, the epitome of arrogance who Bell did so well on stage, Richard III, Macbeth, Coriolanus, Julius Caesar and so on) — “serve us well right to the present day”.

Bell writes with candour about his own decades running a place full of actors — “ … you can be democratic only to a point” — and with humour overall, aided and abetted by cartoons from Cathy Wilcox. There’s one illustration of a woman behind a desk, inspired by Richard III, that recalls the recent shenanigans at Australia Post: “My kingdom for a Maserati.”

Bell finishes each chapter with a series of dot points on leadership, often drawn from Shakespeare’s characters. With Caesar, for example, one of the lessons is that no matter how wise and powerful one might be it’s good to listen to advice. Beware the ides of march and all that. The advice drawn from Macbeth’s blood-spattered rise and fall makes me laugh. Don’t butcher your monarch in your own house (that one’s from me). This one’s from Bell: when three weird witches draw up a blueprint for your future, read the fine print! Macduff was not of woman born, Birnam Wood did come to Dunsinane.

Overlooking that sort of fine detail is enough to make you lose your head. Speaking of which, decapitations are prominent in the excellent 12-page appendix to Harkup’s book that lists all the deaths in Shakespeare’s plays. And this is the demise of named characters only, not the loss of the thousands of nameless soldiers at the battles of Agincourt (Henry V) or Bosworth Field (Richard III) and in other military scrapes and skirmishes.

Topping the body count is Titus Andronicus, “the most bloody of all the plays in the Shakespeare canon”. I like attention to detail here: Chiron and Demterius receive two columns. Column one: “Throat cut”; column two: “Then baked into a pie.’’

Why so macabre?

Of all of Shakespeare’s plays just one, The Merry Wives of Windsor, is free of death, though even there it is alluded to. And it’s not just the beheadings, hangings, hackings, piercings, burnings, poisonings, drownings and bear attacks (Antigonus in The Winter’s Tale), but also the disembowelments, eye gougings and removal of tongues and other body bits.

As the English author points out, her 16th and 17th-century compatriots were on nodding terms with the Grim Reaper. The average age in Tudor England was 38. Public executions were common, and free. Ditto floggings and dismemberment. Severed heads were displayed on spikes for anyone who missed the live show.

“In terms of spectacle, theatrical performances had to give value for money,” Harkup writes. “Shakespeare scattered violence, blood and gore liberally throughout his plays.” He was far from alone and, in the author’s opinion, when compared with John Webster (The Duchess of Malfi) and George Peele (who co-wrote Titus Andronicus), he was “quite restrained”.

Restraint on the page was the author’s choice, but restraint on the Renaissance stage was dictated by the limitations of the special effects. No CGI back then. Hence battle scenes and executions tend to happen off stage. As something had to happen on stage, this led to long pre-execution speeches. The Duke of Buckingham has 58 lines between condemnation for treason and decapitation in Henry VIII. As the author notes, those in the cheap seats at the time may have complained that the Duke left them “standing in the rain for half an hour while slowly talking through a lifetime of crime”.

Blood was easy enough to do, sourced from animals, but unconvincing severed heads would be spotted by the audience because “the real thing was visible on spikes not far from the theatre”.

And even blood could be tricky. In Julius Caesar, for example, Marcus Brutus, having left stage after helping kill his friend for the good of Rome, has just 43 lines (spoken by Marc Anthony) to clean the blood off himself before he has to return.

There is an insightful chapter on suicide, which is committed by more than a dozen characters including Ophelia in Hamlet, Cleopatra (one of the snakebites of the book’s subtitle), Romeo and Juliet.

“The portrayal of suicidal characters in the plays and poems is not only deep in understanding but also surprisingly modern in attitude,’’ Harkup writes. “Shakespeare went a considerable way to show a more compassionate view towards those that contemplate and bring about their own death than might be expected from the time in which he was writing.”

John Bell thinks Shakespeare was emotionally ahead of his time, too, especially in his nuanced and bold portrayal of women (who, when he was writing, were not permitted to act on the stage).

In a chapter titled Integrity and Humanity, Bell admits “it’s not easy, scanning a list of Shakespeare’s male protagonists, to find a man of unimpeachable integrity”. He thinks Brutus comes closest.

He argues the real integrity, though, lies with the female characters: Desmedona in Othello, Portia in The Merchant of Venice (though there’s an amusing aside where he remembers asking two judges for their opinions on her behaviour), Hermione and Paulina in The Winter’s Tale and the one I suspect is his favourite, the disowned youngest daughter Cordelia in King Lear, who he compares with Abraham Lincoln and Nelson Mandela.

Let’s finish with the king killer Macbeth, who Bell sees as particularly relevant today. “I guess the kind of ambition that drives Macbeth is neither strange nor unfamiliar to us,’’ he writes.

“Australian politics over at least the last decade has given us a continuous soap opera of contenders bullying or grafting their way to the party leadership, while in the corporate or financial world you’re not going to get far without a good strong dose of killer instinct.”

Yet when there is a crisis on the horizon, the common but mistaken response of our leaders is to “hunker down and pretend it’s not happening”. That, Bell argues, is not leadership.

“True leadership, as Shakespeare demonstrates again and again, is a quality that entices us to be better and braver that we ever thought we could be, and to create a world that is better than we could have imagined.”

Stephen Romei is a writer and critic.

Some Achieve Greatness: Lessons on Leadership from Shakespeare and one of His Greatest Admirers

Illustrations by Cathy Wilcox

Pantera Press, 270pp, $29.99

Death by Shakespeare: Snakebites, Stabbings and Broken Hearts

Bloomsbury, 368pp, $28 (HB)