Blindness and Rage: Brian Castro’s Novel in Thirty-Four Cantos

Brian Castro has been a great innovator in Australian fiction for decades.

Brian Castro has been a great innovator in Australian fiction for decades. After winning the 1982 The Australian/Vogel’s Literary Award for his first novel, Birds of Passage, his originality took him down a path of semi-obscurity and penury studded with complex but brilliant novels such as his reimagining of Sigmund Freud’s wolf man in Double Wolf, or his intriguing take on the spy novel in Stepper.

His novels won prizes and a small but dedicated audience, but it was his 2003 fictional autobiography Shanghai Dancing, in which the protagonist, Antonio Castro, returns to Shanghai in a quest to understand his family heritage, that broke through to a wider readership.

Subsequent works include The Garden Book, set in the Dandenongs outside of Melbourne; Street to Street, a figuring of the tragic life of Sydney poet Christopher Brennan as well as a wry commentary on the absurdities of the humanities in the contemporary university; and The Bath Fugues, a three-part interrelated narrative, loosely structured around Bach’s Goldberg Variations.

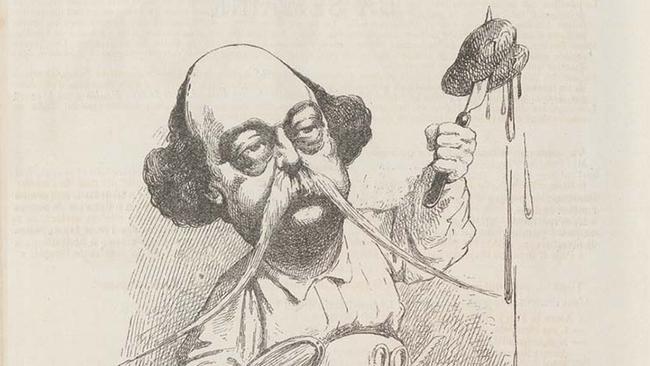

Castro’s work often features strong juxtapositions of subject, location, time and style. In Blindness and Rage: A Phantasmagoria: A Novel in Thirty-Four Cantos we are confronted with Lucien Graq, a retired town planner and failed epic poet domiciled in the Adelaide Hills who has been given 53 days to live.

The post-colon components of the title are instructive of what to expect. First, this is a verse novel. Second, it is a phantasmagoria, a work whose reference to reality is perpetually in doubt. It’s a tactic used by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

Graq is telling us a story but is it just a dream, the lucid dreaming of morphine-fuelled palliative care? It’s hard to know. Certainly the book possesses the in and out slipperiness of morphine days: floating transitions; the childish delights of chimed rhymes; silly puns; as well as the sudden terrors of what comes next, good reason perhaps to forestall the clarifying energy of narrative momentum.

The poem goes to Paris, first through Graq’s engagement with some of the more idiosyncratic players in modern French thought, such as pornographer cum philosopher Georges Batailles and Raymond Queneau, Oulipean, mathematician and author of the wonderful Exercises in Style. Castro uses Graq as a vehicle for the exploration of literary fetish. Paris has long served as the venue for the fixation with utterly literary lives. In Paris, or in his fantasy of Paris, Graq joins an exclusive all-male literary society, Le Club des Fugitifs, which promises to publish posthumously the work of its members on the proviso they abide by a fixed date of death. The closeness of actual death incites an intense longing, probably also phantasmagorical, for his neighbour, pianist Catherine Bourgeois, who is “as beautiful as anyone misted / in the annals of great romantic love”.

Castro’s verse is erudite and playful, full of irresolution and contradiction. But it’s also somewhat uneven and at times lacks poetic muscle. In fact the strongest part of the book is when Castro reverts to prose in Canto XXVII, in the form of Graq’s love letter to Catherine. Instantly there’s a heightened sense of rhythm and sinew that the verse too often lacks. Poetry is more than a matter of chopping up sentences into lines. His verse does have its pleasures, however. There are riddles, for instance:

The Raymond playing solitaire / was overhearing words from everywhere. / “We once had an applicant, / Louis Ferdinand,” he interjected, / whom we rejected as to keen/on proving a mathematical basis / for prejudice. He was a doctor, / had visited Africa, / employed a jungle of prose / and thought himself a big-game hunter, / joining a safari eager to foreclose / on religion and race; / his mother a humble maker of lace/who kept the family alive / in a tenement, turning a trade / from a hive of thick resentment. / Loco, la como, his motive behind the hide / of his writing desk was soon caught /out in his train of thought, revealing / a skilled shunter on the question of genocide.

This is a potted biography of Louis-Ferdinand Celine, author of the brilliant Journey to the End of the Night, who sided with the Nazis and their anti-Semitism in World War II and was declared a national disgrace.

In keeping with the influence of the Oulipeans and others, Castro also has filled his verse with puzzles, most notably a kind of word search where instead of whole words being found in a sea of letters, literary titles are dropped decontextualised into the poem. His playfulness extends to the pleasures of cheesy rhymes. In Canto IX, for instance: “Lucien Graq did not post his letter. / He thought it better / to be curled up in his doona / wishing he had taken up the offer / of a residency in Varuna.” It’s a verse choice that seems more apposite to the Adelaide Hills and its potential for bush poetry than for a voyage into French modernism’s literary avant-garde. But then this is a typically Castro ploy, mischievous and destabilising.

Still the lines quite often feel in need of tightening and there are reaches for rhymes that needn’t be reached for. The consequence is entropy. While the avoidance of momentum is a function of Graq’s attitude to his predicament, verse novels are difficult things and some narrative tension is usually necessary. While there is much to admire here in the microcosm, the whole doesn’t quite maintain the interest that the frequent sparks of brilliance deserve.

Ed Wright is a writer, poet and critic.

Blindness and Rage: A Phantasmagoria: A Novel in Thirty-Four Cantos

By Brian Castro

Giramondo. 224pp, $26.95