Bionic ear surgeon Bill Gibson celebrated in new biography

Thousands of people in Australia can now hear thanks to their bionic ear, and that is largely due to Bill Gibson.

It says much that surgery to implant the bionic ear is no longer considered newsworthy. Thousands of people in Australia are walking around with one, and that is largely due to Bill Gibson, known widely as “the Prof” by many of those he has helped to achieve a normal life.

He is not widely known outside medical circles, and this book is meant to remedy that. Gibson readily co-operated with Tina Allen, an experienced medical scientist and writer, but he sometimes seems a bit bemused about the project. He simply is not the celebrity type. He is the type who goes fishing with mates and dresses up as Santa Claus for children’s parties.

Although he seems very Australian, he was in fact born in Britain. He comes from a family of doctors and there was never much doubt that he would become one. He studied in Britain, where he gained his qualifications, and was drawn to audiology because of the breakthroughs taking place in the field. In particular, Graeme Clark and his team in Melbourne were examining ways of using new technology to help deaf people, focusing on the cochlea, the part of the ear that passes sounds to the brain.

There was already a primitive version of the bionic ear available but it provided only a dot-dash sort of sound. Developing this into a multi-channel device that could convert sounds into electronic impulses that the brain could “hear” was a huge step forward. Gibson came to Australia in 1983 to follow it up, seeing the opportunity to knit his surgical expertise to the device.

Allen is adept at explaining the technology and how it evolved from its shaky beginnings, growing from rough experiments to a commercial model. In 1984 Gibson implanted the device in two women who had lost their hearing, with good results. Further refinements of the device followed and the surgical procedure became more routine.

There were, inevitably, failures as the medical teams learned more about distinguishing between patients who were suitable for implants and those who were not but there was a sense of solid progress. The device became compact and Gibson developed a way to implant it using a small incision rather than a large C shaped one.

The first generation of recipients were people who had lost their hearing in adulthood. This meant they understood the concept of speech and of spoken communication. Gibson formed the view that while restoring hearing to adults was important the focus should be on young people, even children, who had been deaf from birth and so had never learned to speak. By the age of seven or so the speech organs had effectively atrophied.

Gibson eventually chose a four-year-old girl for an implant, which involved convincing medical regulators that the process was ethical and practical. It worked, and the little girl learned to both understand and use speech. Gibson was able to leverage the success to push the age threshold downwards, to children under the age of two.

Along the way he helped establish CICADA — Cochlear Implant Club and Advisory Association — a group than enables implant recipients to meet regularly, providing support to each other and feedback to doctors. (This biography was commissioned by CICADA.)

As the success rate improved it became easier to obtain funding for specialist facilities and post-op therapy. But there was one group that criticised and attacked Gibson, as well as others in the bionic ear circle. The Signing Deaf group took the view that congenital deafness should not be seen as a disease to be “cured”. Instead, the focus should be on teaching deaf children about signing, which should itself be seen as a valid alternative language. Allen notes this idea is difficult to understand but she acknowledges that it is deeply held by some.

Gibson, for his part, listened to the view and was sympathetic to the idea of removing any trace of social stigma from deafness. But he looked more to the real-world picture, which was largely of people delighted to be able to participate fully in the world.

Eventually, Gibson notched up more than 2000 implant operations.

As he nudged 70 he began to move out of the surgical side, but at 73 he still assists and consults. He thinks of retirement, apparently, as dropping down a gear rather than switching off the engine.

This is a fascinating story but, as biographies go, there is not much in the way of narrative tension. Even Gibson’s brush with cancer receives only a few paragraphs. Basically, Gibson has lived a good life filled with good works. Nearly everyone who has had anything to do with him has only warm words to say. Judging from the photos included in the book, he and his wife of many years remain deeply bonded.

So if you want to read about personal sturm und drang or this month’s celebuwreck, then this book is not for you. But if you want to find out about how the world was made a better place, then it is a good place to go.

Derek Parker is a writer and critic.

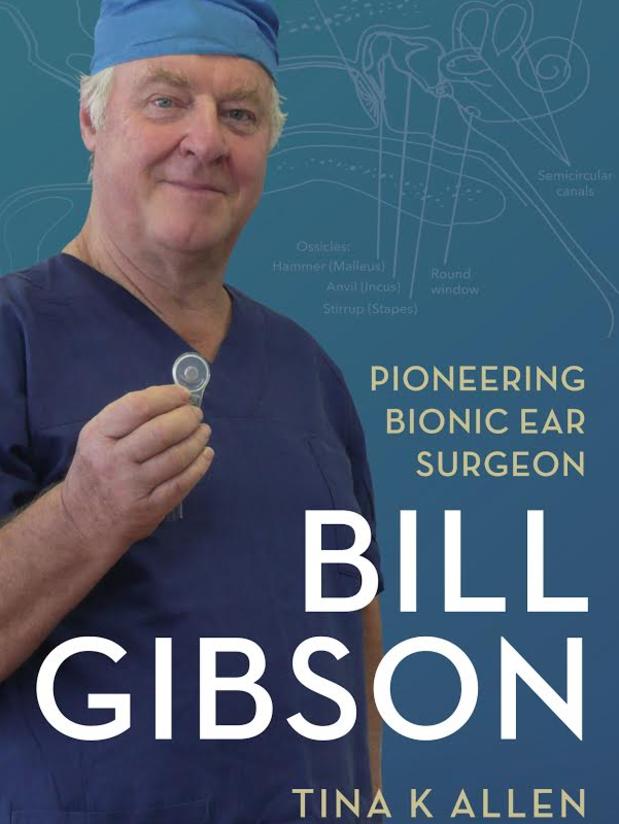

Bill Gibson: Pioneering Bionic Ear Surgeon

By Tina Allen

NewSouth, 302pp, $35

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout