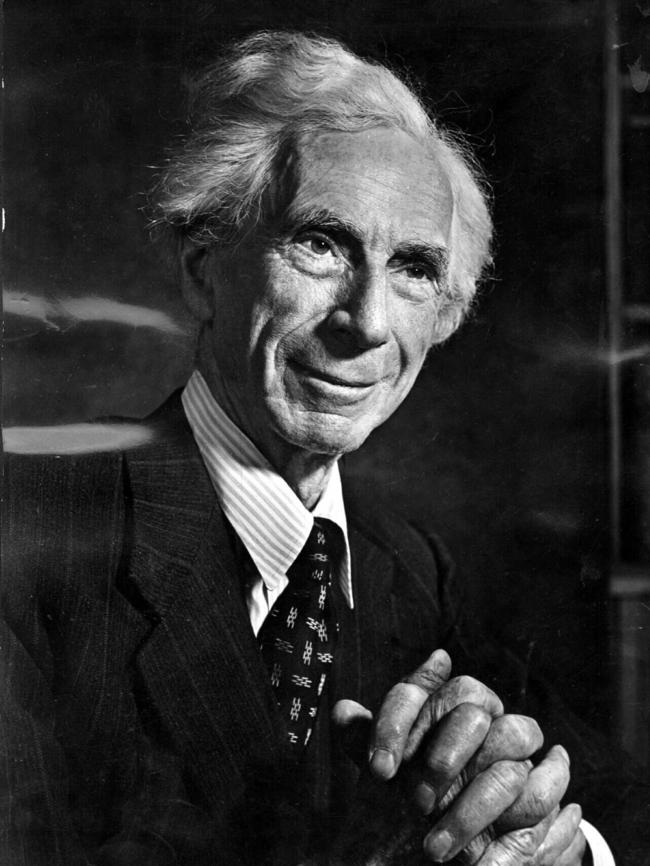

Bertrand Russell: the philosopher who foresaw our future

Bertrand Russell knew that keeping Australia for white men would eventually leave us vulnerable to Asia, and envisioned a safe refuge for Western civilisation in case Europe was destroyed. He was eerily prescient about climate and Russia, too.

When I was was asked to write about Bertrand Russell’s first and only visit to Australia, I shared my excitement (and trepidation) on Facebook, eliciting a flurry of posts from Aussie friends. Many reminisced about their grandparents excitedly attending the great man’s lectures or their parents shooshing their families to listen to him on the radio. However, my favourite, came from a younger journalist colleague: “Got time for a ramble tomorrow or will you be deep in Bertrand Russell? I’ve loved him since I got laid once by reading In Praise of Idleness in a Newtown pub as a teenager”. I recount these posts not just to share the laugh but because for me, they served to reinforce Russell’s continuing, vivid, indeed vivifying presence in so many lives, even half a century after his death.

I began my immersion into his first and only foray to the antipodes, contained in a doorstop volume, just as the world’s news media descended on Glasgow for the UN climate change conference. Russell’s initial observation about Australia, one of the drier nations on earth, struck an immediate chord: “A country of boundless possibilities”, he said with the caveat that a prosperous, fecund Australia would require “a college of highly skilled scientists of various sorts, meteorologists, agronomists, nuclear physicists and so on, to be engaged permanently in a theoretical investigation of what is necessary to increase the fertile area of Australia,”

“It may be said that all the troubles from which the world is suffering are due to the fact that politics lags behind science and technique” he added.

How potent (and poignant) to read his now 70-year-old words at a time when Australia, increasingly ravaged by catastrophic drought and bushfires, is still mired in debate about the anthropomorphic origins and science of climate change.

The invitation to deliver a series of lectures Down Under originated with Edward Clarence Dyason, a wealthy Australian mining engineer turned stockbroker instrumental in founding the Australian Institute of International Affairs (AIIA) in 1924. Dyason had lived abroad for many years but in 1949 launched and funded an annual lecture tour by an overseas scholar in a bid to foster a greater understanding of Australia’s position in the world and bridge what he saw as a dangerous gap between wider society and academia.

Russell was well into his eighth decade when he embarked on the air journey from London on June 19, 1950, with stops in seven cities before landing in Sydney three days later, on June 23. Reportedly exhausted, he still found the energy to conduct an impromptu press conference for the waiting press corps in Darwin before flying overnight to Sydney where, after just a couple of hours rest, he recorded a first talk for the ABC and a session with Movietone News. This first lecture was aired the following Sunday on the ABC’s then flagship Guest of Honour program and its subject matter – apart from the need for science to find ways to make artificial rain – is discomfiting today, focusing as it did on the problems of keeping Australia for white men and the dangers of potential invasions from Asian neighbours. Biological racism was abhorrent to Russell, and he was avowedly pro-intermarriage, but he didn’t question the White Australia policy throughout his tour, perhaps unaware of the bitter resentment it provoked among our neighbouring nations but most probably because it remained so much part of our culture at the time. However, the Canadian philosopher and Russell scholar, Nicholas Griffin, observed wryly that this address was unique among Russell’s Australian lectures in that it did not provoke the vociferous opposition of a clergyman.

Several newspapers chose to run lengthy scene-setting comment pieces before his arrival including The Sydney Morning Herald which published a remarkably informal interview with “the puckish old man with the halo of white hair, the comfortable pipe and face of a mischievous monk” who told the correspondent he’d always thought of Australians as “being rather like Americans … with more drive and self reliance than the English.” The correspondent responded, writing: “It seems we shall all need all our drive and self reliance if we are going to achieve what Lord Russell is going to urge us to do … with a background theme of ‘Ferment in Asia’, he is going to hammer on Australian anxieties and tell us they will probably come true unless Australia develops the north and populates to 50 million…”

It’s important to remember that this was a time when Australia was starting to distance itself from Britain, beginning the slow and inexorable path toward the formation of a new national identity. The White Australia policy remained in force but for the first time, we had opened our doors to large numbers of non-British migrants, including refugees from Eastern Europe. Nevertheless, while the population remained principally white, it was also a period of high domestic anxiety about the Cold War and our geographical position and proximity to Japan and emerging communist countries such as China. The Australian Citizenship Act had only been enshrined into law the year before Russell’s arrival while the federal government continued to try to foster closer economic, diplomatic, and cultural links with the United States.

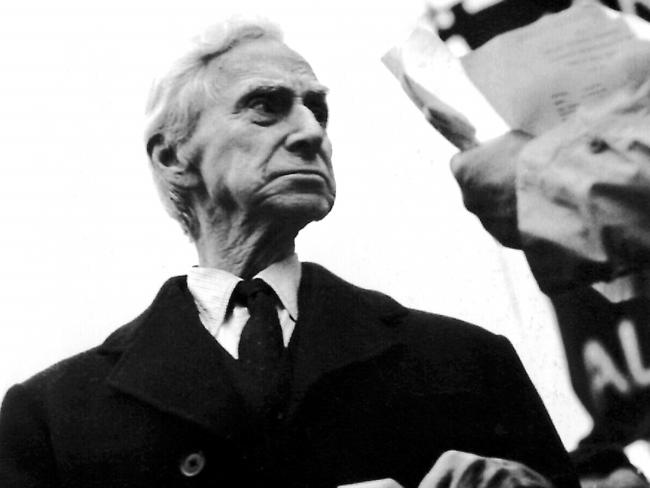

Russell selected six broad topics for his Dyason lectures, chief among them, his passionate and longstanding belief in the need for an overarching world government to stop the outbreak of another war. He warned about the perils of communism and Russian Imperialism, the importance of science and investment in technology for development and the need for youth to foster dynamic, fresh ideas in the new world.

In Sydney, the first lectures titled “Obstacles to World Government” were delivered to capacity audiences and were followed by another three on similar themes. “Ferment in Asia”, a private talk to AIIA members, exhorted the elimination of “what remains of British, French or Dutch Imperialism”. A similar discourse which condensed the three “Obstacles to World Government” lectures was delivered in Brisbane, Canberra, Adelaide and Perth, raising the odd eyebrow about subject repetition.

In Melbourne, however, Russell delivered an entirely different program and chose to focus his thoughts on “Living in the Atomic Age”, writing separate, wide-ranging forays exploring its effect on both individuals and institutions. Throughout though, Russell returned regularly to his theme that Australia’s future lay in investment in science and technology to transform the continent’s vast and parched interior into bountiful lands that could support construction of a new society. This ideal, seen through the lens of the British settler/pioneer who strived to tame and conquer nature via agriculture, failed to recognise the long, successful, and symbiotic relationship between Australia’s Indigenous peoples and the land. At the end of his tour however, Russell did speak pointedly and critically about public attitudes to Aboriginal people, observing that police and private citizens seemed “unwilling to grant [them] elementary rights of justice” although these comments were not widely reported by the media.

Russell had made a handful of modest demands before his arrival, including the need for two hours solitude each day, a preference for seeing the countryside and an abhorrence for functions prompting his hosts to try very hard to ensure official engagements didn’t swamp his time. (He also stated dryly that he had no desire to be hosted by governors). He was able to visit the spectacular eucalyptus forests and sandstone formations of the Blue Mountains outside Sydney, sailed the Harbour, spent a weekend in Central Australia, in Alice Springs, explored the magnificent McDonnell ranges and was struck by the red sands and rust-coloured mountains of Western Australia adding a visit to the gold mining town of Kalgoorlie. Australia wouldn’t figure large in his autobiography (and he was rather less flattering about our “dull” landscapes in letters to friends) although he was very impressed by the sheer ambition of the Snowy Mountains Hydroelectric Scheme.

The period leading into the Australian tour had seen a significant shift in Russell’s thinking, from conventional defences of western Cold War military strategies to becoming a “true antinuclear prophet and sage”. Troubled by overcrowding and ideological tension in Europe, he seemed to envisage Australia as a buoyant alternative, a place where English culture, indeed western civilisation more generally might be transplanted, fed by the dynamism of youth. Australian scholar, Jo-Ann Grant observed that this notion of a science-led pastoral utopia for Australia saw him imagine “a safe refuge for Western civilisation in case Europe was destroyed in a possible Third World War…” Ever anxious about the potential for unlimited global conflict, one can only imagine his feelings when North Korea invaded South Korea just two days into his two-month tour.

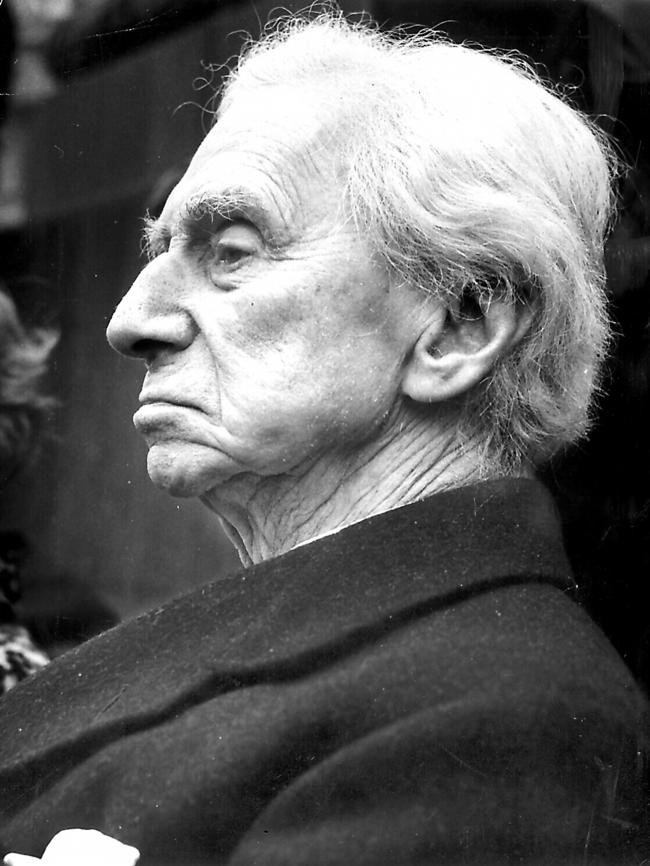

Russell’s sense of apprehension in the early 1950s was probably also heightened as his travels to Australia occurred during a period his biographer, Ronald Clark, described as fraught with “frequent physical upheaval and almost constant emotional strain”. He had recently moved house from the peace and seclusion of north Wales to Richmond in south west London, renovating to make space for his troubled son, John, daughter-in-law, Susan and their three, young daughters. He remained in the throes of an acrimonious break-up from his third wife, was involved in a relationship with a long-term love, Miriam Reichl and would then renew his acquaintance with and in due course, marry his fourth wife, Edith Finch. (Just two years later, his son and daughter-in-law announced they were leaving and left the three grandchildren to the care of their newly married, 80-plus year-old grandfather, a life chapter I found fascinating and entirely unimagined.) And yet the two years after his antipodean foray were his happiest in marriage, extraordinarily prolific and resulted in two books and an astonishing 65 articles and essays which would become the first two volumes of his autobiography.

Russell was treated more like a visiting foreign dignitary by our government than a thinker and private citizen, and the public also responded to him with great affection and acute interest. He appeared before capacity crowds and on a couple of occasions organisers were forced to use loudspeakers to broadcast his speech to overflow audiences outside. The AIIA kept records and more than 12,000 people heard him speak. Notes taken by a Victorian branch member on August 5 made me smile: “He holds his audiences amazingly – practically no coughing, which is most unusual in Melbourne”, although press reports show that he wasn’t received entirely uncritically either, managing to elicit the ire of both the Australian Communist Party for his “Living in the Atomic Age” speech and the Catholic Church for his support of birth control. (He also locked horns with the Archbishop of Melbourne, Daniel Mannix who wrongly suggested he’d been banned from the United States and was forced to issue a public apology.) He was deeply struck by the Australian instinctive suspicion of government, observing Aussies seemed “more impressed by activities which the government forbids than by those which makes it possible.” Few would disagree today.

As an expatriate (Italo) Australian, it seemed almost surreal to see how wider society was energised and excited by the arrival of a philosopher on tour. And it was a breath of fresh air to read just how hard Australia’s editors vied for Russell to write for them. In fact, many articles were proudly billed as “exclusives” despite similar pieces being published in other capital cities under different headlines. In one, headlined “I’d like to Be Born an Australian” for Adelaide and “If I were young and Australian” in Melbourne – Russell wrote mournfully of British and French culture being “infected with a certain weariness” and its “deadening and depressing” effect compared to the joys of Australia, her “hope, vigour and happiness”.

Still, he warned Australians have a “taste for uniformity and humdrum mediocrity” while men of creativity usually display something of the anarchic in their disposition, “men of whom their neighbours disapprove”.

“If a country is to produce truly great individuals, it must add to the four freedoms a fifth – the freedom to be eccentric.”

In 2022, I don’t think I’d be alone in wishing this were so.

The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell: Cold War Fears and Hopes 1950-52, edited by Andrew Bone, Routledge, London and New York, 2021); The Spokesman, Bertrand Russell 150, edited by Tony Simpson and Tom Unterrainer, Bertrand Russell Foundation, London 2022.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout