Beck Hansen looks to a new horizon

BECK’S individual musical style has been forged in a tough furnace.

AS his resume demonstrates, Beck Hansen has a healthy disregard for convention. He likes to mess with its head. Here is an artist whose last collection of songs, 2012’s Song Reader, came only in the form of sheet music; who in 2009 assembled a rotating cast of fellow performers to record in a day versions of classic albums including The Velvet Underground & Nico, Songs of Leonard Cohen and (in 2010) INXS’s Kick. This is the songwriter who in the early 1990s shook up primitive blues with a cocktail of pop, folk and hip-hop, who mimicked the 90s slacker subculture into a delicious few minutes of angsty singalong with the song Loser and who, since the albums Mellow Gold (1994) and Odelay (1996) set him on the path of stardom, has recast himself as sensitive singer-songwriter, avant-garde funk-master and melodic pop craftsman more than once on the same album.

Today the 43-year-old Los Angeles muso has been working in a local recording studio on an album we can expect to hear later this year. He describes the work as “up and energetic and fun and free”, a critique that should whet the appetite of Beck devotees. Further details are harder to come by, partly because his record company, Capitol, would rather keep the project, which began more than a year ago, under wraps until nearer completion.

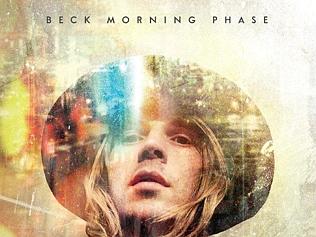

A potentially short conversation is averted by the fact that Beck has another, complete, album under his belt, the less energetic but artistically stylish Morning Phase, released yesterday, his 12th studio album in a career spanning 21 years. This collection of 13 songs, culled from a much larger batch written during the past five years, has, for a number of reasons, jumped the queue in the Beck production line.

We’re in a mixing room on the second floor of the Capitol Records building, a landmark music industry turret just off Hollywood Boulevard where back in the day Frank Sinatra, Gene Vincent, the Beach Boys and scores of others carved their names in pop history down in the basement studio. Beck, who has just driven from his other recording project across town, is familiar with this place too, having employed his musician father David Campbell to record strings on six of his albums here, including the new one and 2002’s beautiful slab of heartbreak and despair, Sea Change, the album from his back catalogue that Morning Phase resembles most.

Beck looks well on his 43 years; in fact he looks much the same as he did when he started out. His slight stature, black leather bomber jacket and blond locks compliment his youthful glow. Only when he talks; softly, pausing for thought and consideration with each answer, rummaging through four decades of debris, gold nuggets, personal lows and musical highs, does the experienced, mature Beck emerge.

He signed to Capitol last October. The label fought hard to get him 20 years ago but lost out to Geffen in a frantic bidding war when the independently released Loser gained traction. Geffen was folded into the larger Universal Music Group in 1999. Beck made his final recording for them, his most recent studio album of original material, Modern Guilt, in 2008. His decision to begin the next phase of his career with Capitol was influenced by his friendships within it, including with former session drummer Danny McCarroll, who until December last year was the company’s president. “I spent a lot of years at my last record company where they had inherited me from a merger,” Beck says, “so I haven’t really been in a place where people were desperate to take my music - not to disparage the other record company; they worked hard and some of the records went really well, but it’s different, someone really wanting you, to just being a kind of foster kid dropped on the doorstep. Everyone I work with has to feel like family,” he says, “otherwise I can’t put my confidence or my heart into it.”

Such close relationships play a part on Morning Phase. Most of the musicians on the new album also played on Sea Change. There’s an alchemy on songs such as Blue Moon, Heart Is a Drum and Waking Light - wispy, folky textures embellished by understated harmonies and subtle strings - that harks back to that earlier work.

He acknowledges a connection between the two albums but is eager to stress their differences. The Beck of 2014 is not the same man who penned Sea Change’s bleak, post-break-up laments Paper Tiger, Guess I’m Doing Fine and It’s All in Your Mind. Sea Change followed, and to a degree documented, the singer’s bust-up with fiancee Leigh Limon, his partner of nine years, who in 2000 Beck discovered was having an affair with a member of LA band Whiskey Biscuit. He describes Sea Change as “the aftermath of crisis, complete personal annihilation”.

However, when put to him that it’s a record that made people cry, he finds the idea amusing. “I don’t mean to laugh,” he says, “but it’s amazing to me how that record comes back to me in the form of people saying they spent meaningful time with it.”

Morning Phase is far from upbeat, but the title is an umbrella for a more hopeful outlook, a light at the end of the tunnel. “I tried to make it optimistic,” he says. “There was a point where it was a lot darker. When I did Heart is a Drum I tried to just leaven the mood a little bit, to give a slight sense of redemption, which perhaps Sea Change doesn’t quite have. Sea Change is more about someone standing in the rubble, whatever sense of their life they had is just decimated, gone. I don’t know if that’s something that just anybody can relate to, but at some point in our lives there are two or three things that affect us right down to the foundations. That’s what that record’s about. As time goes on you realise there are those times where things are really rough, but at some point you are going to have to get to living and some sense of normal again. It’s like if you were in a house that burned down and you had to rebuild it. You wouldn’t be quite at ease but you still have to go on living - find light and find hope and all of those things.”

THERE appears to be no shortage of light and good fortune in Beck’s life these days. Much has changed since 2002. The singer married actress Marissa Ribisi in 2004 and the couple has two children, son Cosimo, nine, and daughter Tuesday, six. They live on the fashionable Pacific coast, near Malibu. When he’s not performing or recording Beck is a family man. He and his wife are members of the church of Scientology. Beck, whose father has been a Scientologist for 45 years, has been involved in the church since childhood.

His success as a musician, songwriter and more recently as a producer working with Charlotte Gainsbourg and Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore as well as on Morning Phase, has brought him wealth and fame, although he’s not one to flaunt them. Such a picture of success is in sharp contrast to the singer’s roots, however.

His parents, Campbell and New York-born visual artist Bibbe Hansen, divorced when Beck was in primary school and he grew up with his mother doing it tough, often with not enough to eat and unable to go to school because he couldn’t afford it. Money was scarce, he says, partly because of a long-term run-in his father had with the Internal Revenue Service.

“I don’t come from a background that had much affluence or stability,” he says. “I didn’t have a safety net. Where I was born was one of the rougher neighbourhoods in LA.

“I took my kids down there recently to show them. I wanted them to have some sense of it. The house I grew up in is still there, which is a small miracle because almost every other house up and down the block has been torn down and they’ve stuck up these cheap stucco apartment buildings. I’m so happy to be out of it. I don’t have any sense of romance about it. I did a lot of time there. I know it well, but I want to live in the environment that’s the opposite of that.”

Beck got out of that environment as a teenager, taking his acoustic guitar and his acquired knowledge of raw blues music on a busking adventure across Europe, then to New York briefly and eventually to the coffee houses and clubs of LA, when he resettled in the suburb of Silver Lake, where he worked odd jobs while hustling for gigs. There was no grand plan to have a career in music.

“I was honestly just trying to survive, to get a job and pay bills,” he says. “All I wanted more than anything else in the world was a $5 an hour job. At the time $4 an hour was the minimum wage, some of my friends were getting $5 an hour and that was a whole other echelon. I really had my sights set fairly low.”

Music, although he didn’t know it yet, was his saviour. “It was something I could access. I couldn’t access the academic world because I didn’t have money to go to school. Music was something I could do with my own hands where I didn’t have to depend on other people to get something done.”

Beck recorded Loser with producer Carl Stephenson in 1992, but did nothing with it for almost two years.

“It’s a strange period because I had a period of five or six years where I was just knocking around and absolutely nobody cared,” he says. “I could barely get gigs. I’d befriend other bands just so I could open for them. That’s how I got entree into a lot of these clubs. Also it was a way to get in free to see these other bands. I had no money. It was something that was more interesting than sitting at home watching the paint dry or trying to catch rats, which was the case where I lived.”

While Loser launched his career in 1994 and the subsequent album Mellow Gold proved he was more than a novelty, Beck had to endure a backlash, sparked by the song that had made his name, which some music fans saw as a cash-in exercise. He has always denied the track was meant to be some kind of anthem for the slacker generation.

“I didn’t get to enjoy any of that success,” he says. “My friends would say ‘what are you talking about? People love that song. It’s on the radio every hour’, but I was dealing with complete negativity on it ... that I was supposed to be ashamed of the song.”

Such misgivings about Beck’s credentials soon evaporated and in subsequent years albums Mutations (1998), Midnight Vultures (1999), Guero (2005) and The Information (2006) confirmed him as one of the most versatile and original American songwriters of his generation.

Everything he had worked hard to achieve was almost undone, however, when he fell and hurt his back while trying to do his own stunts for a video in 2005.

“I filmed a video [for the single E Pro] where I had to do all of these acrobatics that I hadn’t prepared for,” he says. “I just showed up. I was thrown into it. I’m fairly physical on stage. I’ve done five-foot leaps and done the splits on stage, so I wasn’t that worried about it.

“Then a director friend said ‘oh you can’t be in among that equipment for more than five minutes legally’. I’d been in there for eight hours. I was in a lot pain while we were doing it, but I didn’t want to complain. The irony is that when you look at the clip it looks computer generated. But everything in it I did.”

The accident could have crippled him and even now, although almost recovered, as he walks around the studio he has a tentative gait.

“I’m just coming out of it in this last year,” he says. “It’s been a gradual thing. There were five years where I was sidelined. It was a lot of things - ribs, back, nerves, torn ligaments. It was an arduous process recovering from it and my doctors weren’t sure if there was a recovery or what the quality of life would be. But now it has surpassed what we were all expecting.

“That’s the good news and that’s what we want to focus on. Things happen to people all the time. There are occupational hazards. I wasn’t necessarily looking out for myself.”

If video has proved problematic for Beck, film is an area where his passions have left him unscathed, physically at least. He has a long-held desire to make a movie. Film is something that has fascinated him since his mother took him regularly to the movies as a child.

“It was cheap: two movies for two dollars,” he says, “real schlocky movies, throwaways from the 50s, but every once in a while I’d see something interesting. Truffaut, Bunuel. So I learned to read subtitles pretty early. My mom grew up in the Village in New York so she liked those kinds of films.”

His other passion, which he says he is trying to “slow down”, is collecting music recorded on reel-to-reel tape, a format he believes is “the closest to the sound of real music”.

His obsession with achieving the best quality audio for recordings is something he shares with his friend Neil Young, who has developed his own digital playback technology, Pono, in the past few years.

“It’s a reaction to a decade and half of MP3s and digital sound,” he says. “I just got sick of it. Neil was playing me his digital format in his car a couple of years ago and it was as clear as day. As musicians we hear how the music is supposed to sound. In the studio we can hear the resolution. He was playing me some Otis Redding and you could hear the air in the room. That air and the sound of human breath - that’s where the emotion is.”

Beck hopes to make it to Australia this year. His last visit was for the Harvest Festival in late 2012 and he has always enjoyed coming to Australia, he says. In the meantime there’s that other album to finish, Morning Phase to promote and a few other projects on the backburner.

As he gets up to leave, Beck takes a moment to soak up some of the history emanating from the basement. “Wow, Be Bop a Lula, right here’ he says, referring to one of Gene Vincent’s Capitol moments. “There’s a lot of iconic music in this place.”

Morning Phase is out now through Capitol/EMI. See review page 6. Iain Shedden travelled to Los Angeles courtesy of EMI.