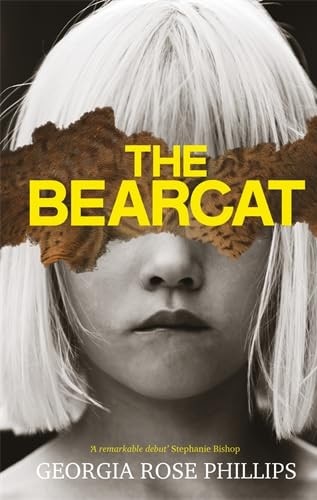

Bearcat: a novel inspired by a cult

Georgia Rose Phillips’s The Bearcat is a novel inspired by the life of cult leader Anne Hamilton-Byrne.

If families make us, can they also be our undoing?

The Bearcat is a debut novel by Georgia Rose Phillips, inspired by the characters behind the notorious Australian doomsday cult known as The Family, whose charismatic and cruel leader, Anne Hamilton-Byrne, died in 2019.

The Family, which had roots in 1960s hippy culture, continues to fascinate: there has been a TV series, The Cult of the Family, and a nonfiction book, The Family, by journalists Chris Johnston and Rosie Jones; and countless interviews with survivors.

This novel presents a psychological portrait of family, selfhood and intergenerational trauma. It is loosely a triptych in structure, and the chapters in the first part diverge between former cult members giving statements to a detective in the 1980s, and the birth of a baby girl, Evelyn, in the 1920s.

The narrative quickly drops the testimony of the cult members, who we only ever know by first letters like M or S, to focus on the lives of the baby and her mother Florence.

Florence is unhappily married to a boozy railroad worker who shows little interest in her as anything other than a “trad wife”: she should bear children, raise them, have a tolerable dinner ready and keep the house clean. Her reluctance to fit that mould earns her the label Bearcat, a 1920s slang term for a fiery girl or woman.

The novel is at its best when exploring the drudgery of domesticity and post-partum depression. Florence vacillates between not wanting to be a mother and wondering whether she’s raising a biblically gifted child. Her daughter Evelyn, demands at a young age to be known as Anne, the same Anne who will later become the magnetic cult leader of The Family, though we don’t see much of this transition, nor the full dynamics which lead to her mother becoming institutionalised, leaving Anne to raise her siblings and handle her father.

While both juggling and rejecting these responsibilities, Anne slowly comes to view herself as the second coming of Jesus Christ.

The book succeeds as a portrait of the thankless indignity hoisted upon women, and the effect this has on generations of its family members. As a study into a notorious cultist leader, however, it misses the mark, at least in my view.

I think readers might fairly feel short-changed by this second element, both because the novel’s rear cover saves its biggest font for the text “inspired by the true story of a notorious cult leader”, and because the hook in its set-up is centred around members of the cult speaking to a detective.

This supplanting of focus may not do The Bearcat any favours, though the psychological character work is strong enough to remain appealing.

I would have preferred more distinctive voices to differentiate characters; each of them reads much the same way. It could alsobe that Evelyn was a child prodigy but in a single chapter, at around the age of 12, she enjoys some of Shakespeare’s lesser known work, wishes she could have a beautiful husband like her father (“who was nice to stare at”), and then smokes a cigar.

Again, perhaps this is simply the facts of history, or the author showing us a tween eager to sample adulthood, but it feels like all the characters of the novel share the same mature, melancholic voice.

Chapters use the years of their setting as a grounding, bouncing from the 1980s to the 20s and back again. Prose often wanders into reverie, melting the past with the present in the minds of its characters. This structure displaces a reader, even as it reinforces the vacillatory role memory plays in the making of self. Humans are messy, our imaginations wander, we’re often hostages to our past. But the overuse of this technique is disorienting, resulting in unreliable telling instead of showing.

At times I wondered whether this was the point of The Bearcat: that the past influences us, without being controllable. The book’s prologue alludes to this idea as it opens with a quote about the fruitlessness of trying to master the past, which does indeed inform Anne’s trajectory as she founds her cult and even names it The Family - though the prologue also introduces us to a German word, vergangenheitsbewaltigung, both foreign and complicated to most readers, much like the weaving of the novel’s histrionics.

The Bearcat features long, frequently poetic paragraphs, that can contain beautiful writing that resolves into some profound understandings, such as the ideas that “some children give birth to themselves” or that “gurus only (have) followers, not friends”.

The trouble is, it doesn’t offer enough, like a diet in need of fibre. The descriptions stacked with metaphors can be unrelenting, and at times it feels as though the author is in a contest with herself to one-up each sentence, while drowning out some splendid writing.

What any novel with complex threading hopes to achieve is the alchemy of A + B = C, where its overall narrative is greater than the sum of its parts.

The Bearcat is missing something in its equation, as though, much like Evelyn-turned-Anne herself, it has an identity crisis in pursuit of a greater purpose.

Cadance Bell is a writer and critic who lives in country NSW.

About the author

Georgia Rose Phillips has written fiction, creative nonfiction, poetry, literary criticism and academic works. She is a lecturer in creative writing at The University of Adelaide. In 2018, her creative nonfiction novella, Holocene, was runner-up for the Scribe Nonfiction Literary Prize. In 2021, her short story, New Balance, was a fiction winner in the Ultimo Literary Prize. In 2022, her short story, Beyond the Marram Grass, was a short-listed finalist in the American Association of Australasian Literary Studies (AAALS) Prize. She is currently working on her second novel and a book-length collection of poems.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout