Bark Ladies: female Indigenous artists are making their mark

Outsiders are often told Aboriginal culture is fixed and that First Nations societies prioritise passing on rites and rituals unchanged forever. But some female artists are breaking the mould.

In the monsoon breeze-cleansed courtyard of an art centre in Yirrkala, a community on the eastern tip of Arnhem Land, Dhambit Mununggurr is painting a larrakitj memorial pole. The design reflects a relationship between the crocodile and the quail. The former, a Gumatj totem, is an ancestral being disfigured by fire, while the latter spreads flames from the Gumatj homeland to other parts of the clan’s estate.

Like so much in Yolngu philosophy, this narrative is deceptively simple. The connection between the crocodile and the quail also resides in similarity between the sound the quail’s wings make when it escapes from the undergrowth and the noise of flames consuming dry grass at the height of the burning season. Both are reflected in a song cycle of which Mununggurr’s design is a mnemonic. The song and its associated dances and ceremonies encode rights over land and other aspects of Yolngu tradition. Thus, Yolngu culture lives unwritten as a disseminated organism within its people.

“I learned this from my parents,” Mununggurr says. “I don’t mind what other people think when they look at this, but I feel proud (when I’m making my art).”

Mununggurr is among 11 female Yolngu artists whose work will show at the National Gallery of Victoria in an exhibition entitled Bark Ladies.

She and her colleagues at Buku Larrnggay Mulka art centre spend their days navigating the mosaic of their ancestral knowledge, reproducing key elements for the benefit of younger generations and for outsiders whom they hope to teach. “It’s part of the normal Yolngu project of trying to educate non-Indigenous people that they’re not living in a world dominated by real estate, that the land has a spirit and an identity wherever you are,” says Will Stubbs, Buku’s co-ordinator.

Outsiders are often told Aboriginal culture is fixed and that First Nations societies prioritise passing on rites and rituals unchanged forever. Intriguingly, the aspects of Yolngu creativity to have attracted the most praise in recent years revolve around the suppleness of stewards such as Mununggurr reproducing their traditions through art.

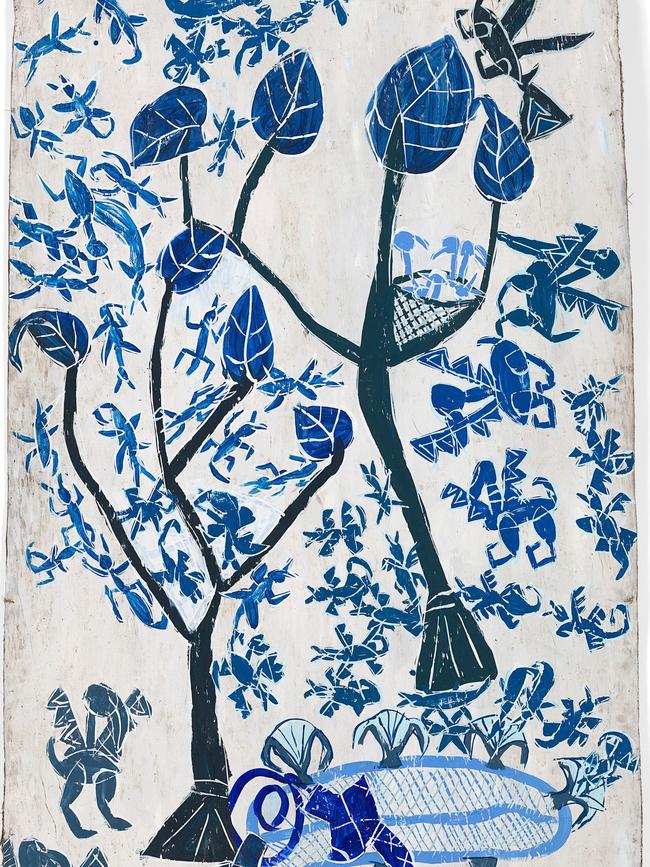

She paints in vivid blue acrylic under a special dispensation from the rule that “paintings of the land must use the land”, granted after a severe accident took away her ability to grind ochre. Her colleague Nonggirrnga Marawilli uses recycled print toner mixed with ochre to create exotic pinks. The late Ms Yunupingu departed entirely from convention and protocols and painted personal narratives instead of sacred designs.

Myles Russell-Cook, a curator of Indigenous art at the NGV, says female Yolngu artists have shown themselves especially innovative. “When you look at Yolngu art and the inherited visual languages that inform contemporary painting, it’s women artists who are working in a way that’s so groundbreaking,” he says.

“For a very long time, painting on bark was linked to ceremony and to inherited cultural practices and was the domain of men … it wasn’t until women started painting in their own right that, really, there was this kind of freedom.”

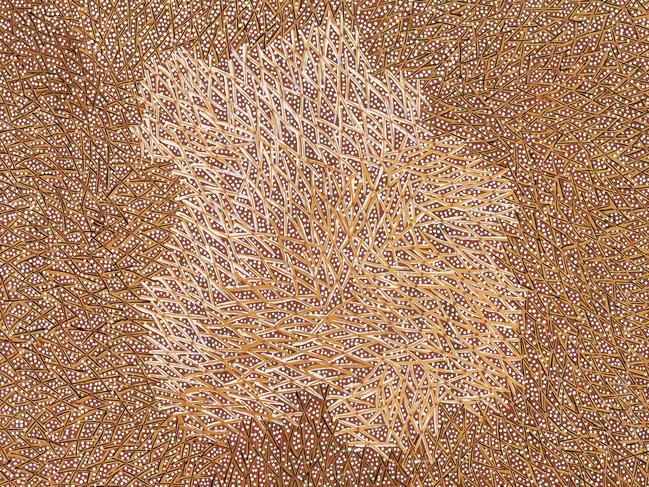

In a room adjacent to Mununggurr’s courtyard, Naminapu Maymuru-White encrusts a bark sheet with delicate symbols of the Milky Way, using a clutch of human hairs.

“I paint not for myself but to show my grandkids, nieces and nephews how it should be taught,” Maymuru-White says.

“I don’t know how I ended up doing this, but it’s my favourite painting. Every time I do it, I think about the people who’ve gone … my message is that you are going home, through the river of stars, to join the others.”

Yolngu say their bark-painting tradition began with body painting during ceremonies. Some years ago, during a land rights battle, Madarrpa leader Djambawa Marawili encouraged artists to set aside prohibitions on depicting ceremonial designs and use them to demonstrate ownership of sea country. Nowadays, Yolngu show sacred minytji (clan designs) in digital form and on found objects including wood, perspex and metal.

To Western-educated eyes, unwritten culture is already somewhat unfamiliar. The way Yolngu preserve their fixed knowledge in ever-changing form, without inscription or central authority, can be pretty amazing – like a book with holographic pages.

Stubbs, who is non-Indigenous, dislikes being asked if Yolngu artistic innovation was stimulated by outside influence, much like the need to show land ownership pushed Marawili to ease the rules on depicting minytji. He says the notion is rooted “in white supremacy”. It’s not clear what he means.

Russell-Cook points out that Yolngu traded with Macassans at least as far back as the 1700s. Some Macassa-linked words are found in Yolngu languages.

It’s tantalisingly difficult, without a written record, to look back and know whether the recent Yolngu taste for artistic innovation supplanted a preference for conventions or whether it has always been so. But not knowing is also what makes now special.

You, too, can participate in the living ark of Yolngu knowledge by visiting these exhibitions and breathing in their lessons. It is better to ask silly questions and join in the “normal Yolngu project” of education than not to care.

Bark Ladies: Eleven Artists from Yirrkala runs at the National Gallery of Victoria from December 17 until April 25.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout