Banjo’s slavery links explored by Laurent Dubois

Smash your piano and pick up an (African) banjo, Mark Twain once said, its music hits you like ‘strychnine whisky’ | VIDEOS

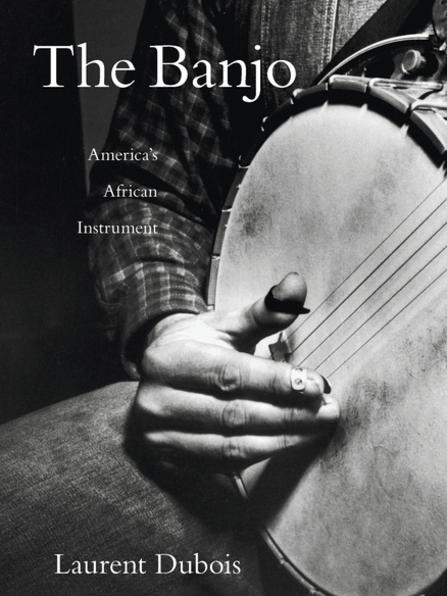

The Banjo: America’s African Instrument, by Laurent Dubois (Belknap Press, 364pp, $39.95)

Watch any YouTube clip of the legendary banjoist Earl Scruggs and his band playing Foggy Mountain Breakdown and you will see a host of America’s most skilful banjo pickers.

What you are unlikely to see, either on stage or in the audience, is a black face — which is strange, given the banjo’s origins as the instrument of African slaves. How this happened is the question at the heart of Laurent Dubois’s riveting history of the banjo.

His tale begins in 10th-century Spain, with a biblical illustration of 16 lutes played by 16 saints. These, however, are not your everyday lutes, made of carved wood with a hole beneath the strings. The saintly lutes have oval bodies covered with stretched animal skins that would have imparted a distinctive hum or buzz. This difference, according to Dubois, makes the saints not lute players but banjoists. “For if there are many ways to define precisely what a banjo is, when all of them are peeled away, what remains is one key, consistent feature: a rounded or oval body covered with animal skin.”

The skin turns out to be crucial, since it determined not only how the banjo was made but where it could be made — and therefore played. Animal skins expand and contract with the temperature. The relatively cold European climate played havoc with skins, causing European instrument-makers to favour wood for their stringed instruments. In the warmth and humidity of west and central Africa, however, skins were easier to manage.

The African climate also suited the cultivation of gourds and calabashes (a kind of fruit), which could be crafted to form the body of the instrument. Similar climates prevailed both on the Caribbean islands where African slaves laboured on sugar plantations and in the American south, where slaves were put to work growing cotton. Hence the African instrument became the instrument of Africans in America and, eventually, of Americans themselves.

Race is a shifting but ever-present theme in the story of the banjo, and Dubois devotes several chapters to analysing the significance of the instrument (and of music generally) to the millions of black slaves who survived the dreaded Middle Passage across the Atlantic Ocean to die on white men’s plantations in the Americas.

For slaves who would never see their homeland again, who were physically exiled from the place where their ancestors had lived and died, the sound of the banjo re-established a connection with Africa. It had a spiritual as well as an emotional meaning. As Dubois writes: “The spiritual meaning of the banjo was about the enactment of an impossible return, about refusing the kind of exile from one’s natal community, and oneself, that the slave system demanded.”

But the banjo, he tells us, was also co-opted by the system. Slaves were allowed — and even encouraged — to play and listen to the banjo by owners who believed that a little musical entertainment would keep them more docile.

Slave traders sometimes used banjo music played by slaves to spice up their sales pitch: the auction block was often referred to as the “banjo table”.

The end of slavery in the US signalled the start of a process by which banjo playing crossed the racial divide, initially in the form of blackface minstrel shows. After the Civil War, troupes of black performers emerged, some of which were owned and managed by African Americans.

Dubois gives an entertaining account of the celebrated 19th-century black banjoist Horace Weston who, in the words of his fellow performer Ike Simond, “made every banjo player in the land lay chilly”. After Weston was turned away by the Union army during the Civil War (no black volunteers were accepted at the time), he signed up with the navy. Weston’s banjo playing was so popular that he received “fifty cents per month from each sailor of the crew for playing for their amusement”.

Mass production transformed the appeal and accessibility of the banjo. By the end of the 19th century, notes Dubois, “the banjo was broadly embraced as ‘America’s instrument’ — meaning that it had also become thoroughly appropriated as a ‘white instrument’ ”. The electric guitar almost killed the banjo, but by the mid-20th century, largely through the efforts of Scruggs, it had been transformed again, this time into a staple of bluegrass. In the 1960s Pete Seeger and his banjo were icons of the white American counterculture.

While the story Dubois tells is primarily historical and sociological, it is also musical, and he never lets us forget the magical hum that distinguishes the banjo from the guitar and other stringed instruments. He quotes with relish the words of another banjo tragic, Mark Twain. “When you want genuine music,” wrote Twain, “music that will come right home to you like a bad quarter, suffuse your system like strychnine whisky … ramify your whole constitution like the measles, and break out on your hide like the pinfeather pimples on a picked goose — when you want all this, just smash your piano, and invoke the glory-beaming banjo!”

A professor of romance studies and history at Duke University, Dubois has previously written books about slavery in the French colonies and about the connections between France’s colonial past and its national football team. Although scholarly in its conception and breadth of research, his banjo book is readily accessible to the general reader.

If, at the outset, Dubois strains at times to sound hip (Ziryab, a black slave in medieval Spain, “may well deserve the title of the world’s first international rock star”; 17th-century African griots, or troubadours, would take revenge if “stiffed” of their expected fees), he soon settles down. There is nothing worse than reading a book about music by a writer with a tin ear, and Dubois combines erudition with obvious enjoyment. His limpid prose easily bears the weight of his impressive research. The black-and-white illustrations are invariably useful, but some colour plates would have been nice.

Tom Gilling is a Sydney author and reviewer.