Bangarra’s next step

For the better part of three decades, Frances Rings has been a quiet but constant presence at Bangarra Dance Theatre. Now she’s taking over the acclaimed company. But what do we actually know about her?

For the better part of three decades, Frances Rings has been a quiet but constant presence at Bangarra Dance Theatre, steadily supporting longtime artistic director Stephen Page as he built his world-class company of Indigenous performers. Many documentaries, films, TV programs and countless news pages and radio hours have, over the years, been devoted to the man Rings is replacing.

But what do we actually know about Rings, who has been with the company in one form of another – dancer, choreographer, artistic associate and now incoming artistic director – for much of the 32 years Page has led the company? What is her vision for the company, the only full-time First Nations performing arts company in the world? And what of Rings herself?

The 52-year-old descendant of the Wirangu and Mirning tribes projects a rare combination of modesty, unquestionable self-belief and sharp intelligence. And Rings may well prove to be just what the company needs as it moves into this important next chapter. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given Rings’s rich choreographic voice, hers is a fascinating story.

“I don’t often talk about my family because I come from a very complicated family structure that doesn’t look like a normal family,” Rings says. She was born in Adelaide to German railway worker Theodore Rings and Wirangu and Mirning woman Caroline Edwards, and so began a happy, noisy, itinerant childhood. Caroline had five children from a previous marriage before the couple had Rings, then her younger sister Gina.

“There was a lot of us and we moved around a lot because Dad worked on the railways, we only settled down when I went to primary school at Port Augusta. When I’m down there I have this sense of sky and light and landscape, it’s very familiar and that’s calming for me because it’s my first memory of place.”

Her parents separated just before she started school and Rings moved to Port Augusta with her father, who ultimately remarried. Although she acknowledges her loving stepmother, who treated her like her own, Rings was disconnected from her mother, something that haunted her for years.

“I didn’t have many early memories of Mum. Much later I had to ask Dad why and let him know it had a real impact on me … he was very regretful and apologetic … some things you have the answer for and some things you don’t.”

It was a modest upbringing but they had everything they needed: food on the table, shoes and basic clothing.

“There were a lot of other people doing it tougher,” Rings says. It was in Port Augusta that she discovered her artistic voice, when Theo made a round, corrugated iron rainwater tank into a cubbyhouse with little cut-out windows and a door. Rings dragged in towels, curtains and other props to create a theatre in which she staged productions.

“I created little imaginary worlds where I could make sense of things, understand my world and what was happening around me. Because I couldn’t see myself anywhere, I couldn’t look to my community or see a picture that looked the way I looked. That sent me on a lifelong quest about identity and telling stories and what makes us who we are.”

It was while studying at the National Aboriginal Islander Skills Development Association that Rings managed to track down and reconnect with her mother, a reunion that would prove pivotal.

“I felt I’d finally landed. I had a mob who recognised me, who I was culturally connected to through kinship and country. That bloodline, it’s important, to know you belong somewhere.”

It also began to sow the seed of future leadership ambitions, cementing her sense of self. “Going down to my own family and communities and seeing cultural governance and leadership [helped me understand] I come from that lineage of leaders.”

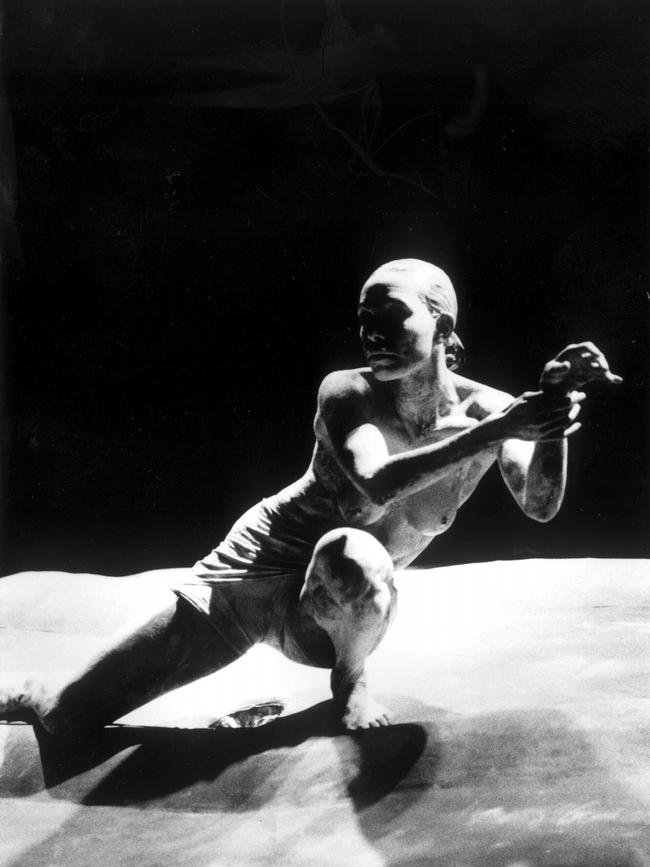

It was also while at NAISDA that the young dance student met the three Page brothers: dancer and choreographer Stephen, composer and musician David and dancer Russell (Russell and David later died tragically, in 2002 and 2016 respectively). The three boys – themselves from a family of 12 children from southeast Queensland – were living in inner Sydney and quickly took Rings under their wing. Rings followed the brothers to Bangarra in 1993, two years after the young firebrand Stephen had taken over as artistic director and choreographer. What followed was a deeply personal and professional connection forged during Rings’s 12 years dancing with the company, before evolving into a successful choreographer, creating a vast body of works that brought to life historical figures (Unaipon, 2004), stories (Artefact, 2010) even the landscapes of Indigenous Australia (Lake Eyre’s Terrain, 2012).

It was while dancing in the Bangarra-Australian Ballet co-production Rites, and later choreographing works with independent companies such as West Australian Ballet, Tasdance and Atamira Dance Company in New Zealand that she developed a sense of the power of collaboration, something she is determined will play an important role in Bangarra’s future.

“When you share stories, share space, you learn new skills, new tools,” she says, referring to West Australian Ballet’s coming Indigenous-informed production of Swan Lake with One Blood Dancers. “When companies collaborate we elevate our artform … I’m excited by the opportunity that could present in the future.”

Rings returned to Bangarra in 2019 to take up the newly created role of associate artistic director, before being announced in late 2021 as the next artistic director from 2023. At the time, Bangarra chairwoman Phillipa McDermott described Page as “a national treasure .. whose legacy cannot be underestimated, he has done so much for this nation [including] his unfailing dedication to his people, his work in bringing culture together through art, which will be honoured forever more.”

While Rings is quick to emphasise her foremost priority is caring for the robust company she inherits from Page and outgoing executive director Lissa Twomey, she is undaunted by Page’s artistic legacy and has very firm ideas about her leadership and the future direction of the company.

“I’m not going to be a leader like Stephen, because I’m not Stephen,” she says simply. “I’m a lot more considered in a lot of ways. I like working collaboratively; I rely heavily on my team, being able to share the experience and authentically challenge each other.”

While nobody would argue Page was fundamental in building Bangarra into the internationally celebrated company it is today, he concedes his leadership suffered at times, particularly following the personal tragedies he endured with his brothers’ deaths when he ploughed on relentlessly, rather than take time out to grieve.

“My big regret is I felt like I let myself down, I let the company down when I just kept creating and pushing through when I was grieving. They wanted more guidance and I couldn’t help them,” Page told The Australian in December.

“I was exhausted … probably very angry, so that’s what they were getting. I think they would have been really disappointed with that type of leadership.” Several senior dancers left at the end of 2018, just as they had in 2003.

Rings is determined to lead collaboratively and nurture young creatives for future leadership in all areas of the company, including choreography, music and design. She also plans to collaborate with independent choreographers and organisations.

“Next year I’m 53. My whole vision for my leadership is about setting up for our future, it’s about cultivating our next creative and cultural leaders, and about how we can do works that are sustainable and aligned to our cultural values of caring for country. I think we can do that more mindfully.”

Rings has put in place an Indigenous creative trainees program in which resident creatives costume designer Jenny Irwin, composer Steve Francis and designer Jake Nash mentor trainees; in addition to the Russell Page and David Page fellowships that support a young dancer and composer working with the company each year. Then in February, Bangarra will present Dance Clan, a season of works by emerging choreographers with a team of early career Indigenous designers.

“We really struggle at Bangarra to find creatives who are First Nations so it’s vital we do our bit to provide opportunities for training,” she says.

Rings is also determined to look to other choreographers.

“I don’t want to choreograph every year; I want to commission incredible visionaries to come and tell their stories.”

Rings has plans only to build on the incredible legacy of storytelling for which Page was renowned through his diverse shows. Her debut production as artistic director, Yuldea, marks the first time she will tell the story of her mother’s country, depicting the rich history – and ultimate destruction – of the sacred site and life-giving source known as Yuldi Kapi.

Located at Yuldea (Ooldea in English) on the edge of the Nullarbor Plain in the Great Victorian Desert, Yuldi Kapi was a site of permanent fresh water located deep within the sand.

Not only would tribes moving across Australia visit the site for ceremonies, trading and kinship, they’d replenish and access fresh water.

“It was a source of survival and of life,” Rings says.

All that changed after Western Australia agreed to join the federated states in July 1900 and a railway line was subsequently built from Kalgoorlie to Port Augusta, using water from Yuldea to resource nearby railway camps and generate power for the locomotives.

Within 20 years of the railway line being built, the water was exhausted, impacting people’s ability to stay on country.

By the time atomic testing began at nearby Maralinga in the early 1950s any families still living locally were forcibly removed due to the resulting dangerous black mist and ash, sent as far as Kalgoorlie and Koonibba near Ceduna, where Rings’s family ended up.

“A lot of those families are still trying to find each other and get back to country today,” says Rings. “This story is about the ambitions of a nation growing, expanding, and becoming industrialised. But at what cost?”

Rings knows well now the country of her mother’s birth, having visited many times while her mother was alive (she died in 2013, Theo in 2011) and returning with her own family, two teenage sons and husband Scott Clement, whom she describes as “a beautiful white fella I’ve been married to 22 years now”.

“It makes me so proud to be able to take my children and show them this beautiful, peaceful place,” she says. “They just love it, the boys go fishing and come back with buckets full of squid and whiting, Scotty could pack up tomorrow and move there. He loves it, he loves the whole family.”

Rings and her Yuldea creative team recently returned from a week on country, talking and listening to elders and community leaders from Yalata, the community on the far west coast of South Australia whose story it is to tell.

She took with her the young David Page music fellow Leon Rodgers whom she’s entrusting with the score for this full-length production, along with electronic music duo Electric Fields who will collaborate on the score. In 2023 they’ll return with the dancers so they too can experience and hear first-hand these stories so crucial to our nation’s history, before bringing them to life on the stage.

“My first and foremost priority is caring for what I inherit,” she says. “But I also want to invest in our future. I want to use Bangarra as the place where we’re not only just saying it, but there’s actual tangible actions we’re taking to ensure we’re investing in our future cultural leaders. And I’m really proud of that.”

Bangarra’s production of Yuldea opens June 14 at the Sydney Opera House before touring to Canberra, Brisbane, Melbourne, Adelaide and Bendigo.