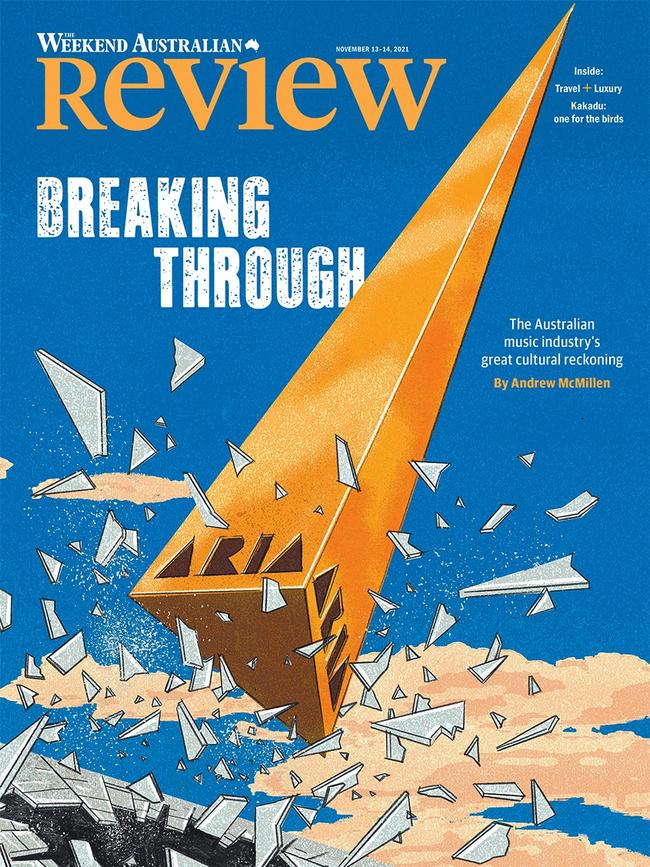

Australian music’s earthquake year: power, abuse and the overdue promotion of women

After decades of male dominance, the Australian music industry is at last promoting women to positions of power amid a great cultural reckoning.

If you listened closely enough, the rumbling had been going on for years. It’s only in the past few months, however, that a cultural earthquake has begun to shake the foundations of the Australian music industry and its halls of power.

The whisper has become a roar which has in turn attracted the attention of regular concertgoers and fans – and those who tune into the ARIA Awards to catch up on some of the great songs and artists they may have missed.

This year, ahead of the annual ARIAs ceremony to be held on November 24, allegations of abuse, assault, bullying and harassment have been amplified to a much higher volume than before.

A reckoning on misconduct is underway at the highest levels of the business, as companies grapple with how to provide safe and supportive workplaces for women in an industry with an unsavoury global history of powerful gatekeepers using their positions for personal gain and gratification.

It has taken a small group of brave individuals willing to put their names and faces to allegations of intolerable experiences, as well as a much larger cohort of women and men who have chosen the path of anonymity – for now – in order to protect themselves, their families and their careers from reprisal.

A major turning point in this ongoing saga arrived on June 21, when Sony Music Australia chairman and chief executive Denis Handlin was terminated from his role after 50 years with the company, effective immediately, via an all-staff memo sent from Sony’s New York head office.

Handlin had spent decades accumulating power and wealth while controlling one of the biggest record labels in Australia, representing artists such as John Farnham, Delta Goodrem, Guy Sebastian and Midnight Oil.

More than four months later, the precise reason for Handlin’s sudden departure via group email remains ambiguous. Sony’s US office has declined to elaborate, and no successor has been announced.

What is known for certain is that after anonymous allegations from current and former Sony employees were sent to head office, the company began an internal investigation of its workplace culture in Australia, particularly at its Sydney headquarters.

Subsequent news reports alleged that bullying and a “toxic workplace culture” – including alcohol abuse – were rife, although none of these allegations related to sexual harassment.

Some allegations dated back more than two decades, suggesting that executives at Sony’s head office were forewarned about questionable staff behaviour under Handlin’s leadership.

Handlin has denied any wrongdoing, telling Schwartz Media in a statement around the release of its investigative podcast Everybody Knows in September: “I would never tolerate treating women in an inappropriate or discriminatory manner. At any time I was made aware of this sort of behaviour, I took action to ensure that it was stopped and didn’t occur again.”

Review approached Sony Music for comment on Handlin’s statement; its US office referred us to the same statement it has been issuing to media outlets since June.

“We take all allegations of bullying, harassment and other inappropriate behaviour from our employees very seriously and investigate them vigorously,” reads the statement. “Only recently did claims surface and we are examining them expeditiously. We are not in a position to comment further on allegations concerning matters which occurred over 20 years ago particularly given that the persons involved at that time are no longer at the company. To the extent these matters have been raised, Sony Music has been reviewing them.”

In a memo to Sony’s Australian staff, sent late on the Monday his termination was announced, Handlin agreed with the company’s global chief executive Rob Stringer that “it’s time for a change”.

His chief role at one of the nation’s three major labels – alongside Universal and Warner – also meant that Handlin held a boardroom seat at the Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA), the organisation established in 1983. He was ARIA’s chairman for all but two of the past 22 years.

Although the role does not have a casting vote or any special powers, Handlin had an extraordinarily long run atop the board of ARIA, which represents more than 100 members across the record industry, from the three major labels to smaller independents.

Handlin’s removal from Sony in June meant that he immediately lost the ARIA board chair role that he had held from 1999 to 2008, and from 2010 to 2021.

It also brought to an end almost four decades of exclusively male leadership at ARIA.

ARIA now has its first female chief executive in Annabelle Herd, who took up the job in February, succeeding Dan Rosen. Her background is in television and politics, having previously worked as chief operating officer at Network 10, which meant that she approached the role – and the music industry – with fresh eyes and few preconceptions.

And ARIA now has its first female board chair in ABC Music head Natalie Waller, who was announced on July 13 following a unanimous vote from her fellow board directors.

Fittingly, this landmark moment arrived not long after a star-studded tribute to Helen Reddy at the ARIA Awards last November, where some of nation’s greatest living female singers – including Delta Goodrem, Kate Ceberano, Marcia Hines, Christine Anu and Jessica Mauboy – sang I Am Woman together while backed by a “virtual choir” on a screen behind them.

“It’s great to have more women in senior leadership roles across the entertainment industry,” Herd tells Review. “I think the fact that it is remarkable, or remarked upon, shows that there’s still a lot of work to do across the music industry.”

The significance of these two appointments – as a step towards gender equality in the music industry – can’t be overstated.

Since ARIA was formed in 1983, the only way to get a seat at its boardroom table was to head up a record label. And since women in those leadership roles were exceedingly rare, only two women had been appointed board directors.

The last of this pair was Vicki Gordon of Transistor Music, who was elected in 2000 to represent independent labels; she resigned in 2002 as a result of leaving Transistor. Before her, Bonita Boezeman was on the board from 1993 to 1996.

In 2019, ARIA broke with its longstanding blokey tradition by adding four women to its board, being ABC Music’s Waller, Libby Blakey of Warner, Karen Don of Universal and Sophie McArthur of Sony.

The move came after ARIA members voted for an increase in diversity and inclusiveness by confirming amendments to its constitution at the 2018 AGM.

“Having more women and people from under-represented groups in senior leadership positions – like chair or CEO roles – means better and more innovative decision-making, which is always a good thing,” Herd says. “And, of course, cultural change comes from the top.”

-

In May, University of Technology Sydney researcher Dr Jeff Crabtree published an academic study into workplace harassment in the Australian music industry.

Crabtree’s research was based on an online survey of 145 music industry workers between March 2019 and March 2021. All but one respondent had experienced some form of harassment at some time in their careers.

He found that 65 per cent of the women surveyed who work in the music industry have experienced pressure to have sex, and 85 per cent have experienced other forms of sexual harassment.

The researcher also conducted anonymous interviews with 33 music industry workers, of which 26 were women; two of them mentioned that they would fear for their lives if their identities were to be discovered.

One interviewee told Crabtree about an experience with a prominent male in the Australian concert production industry. After she told him she wanted to learn to be a lighting technician, “He looked at me as if I was just shit on him or something,” she said. “He started laughing, he said: ‘Sweetheart … there’s only two places for women in this business: either at the door or on their back.’ ”

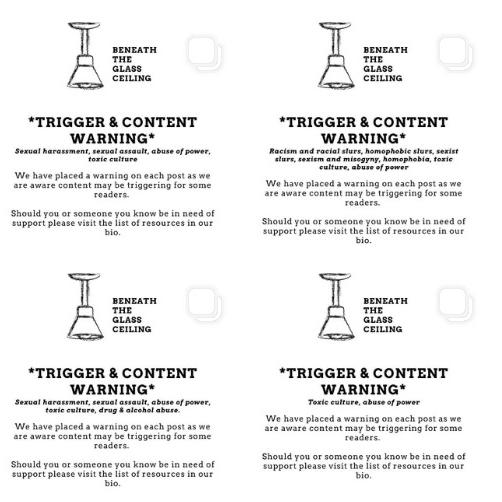

His findings coincided with the rise of an anonymous Instagram account named Beneath the Glass Ceiling.

In November 2020, the account began publishing redacted survivor stories of individuals who sought to highlight alleged abusive behaviour while avoiding defamation laws. It now has more than 15,000 followers.

Its drip-feed of anonymous stories became a wave that implicated the corporate culture at Sony Music Australia. The results of Sony’s investigation into its workplace culture have not been revealed.

On July 30, Universal Music – the global pop market leader in terms of overall revenue – announced that it too was undertaking an internal investigation into the workplace culture at its Australian office.

The company engaged a law firm and encouraged its staff to raise any concerns through internal and external complaints channels. Allegations about Universal published by Beneath the Glass Ceiling included multiple claims of bullying, harassment, racism, homophobia, discrimination and sexual assault.

In an email to his staff, Universal Music Australia president George Ash wrote, “As the leader of this company I take full responsibility for creating a respectful workplace culture for everyone. With respect to my own behaviour, it is particularly painful to realise now that what I intended as jokes were unacceptable comments that made some of you uncomfortable.”

In an interview with Nine newspapers in August, Ash said, “My initial response was, ‘I don’t know whether the allegations are true or not’ but it made me think we haven’t done enough and we need to do more in our company. I need to step up and take responsibility.”

Following the publication of Crabtree’s research, ARIA held a meeting on May 25 to discuss how it could start the process of cultural change, with an immediate focus on addressing sexual harm, harassment and systemic discrimination in Australian music.

Almost all of the 35 attendees – both in person and via online video – were women. “It was a really difficult conversation, but it was extremely respectful,” recalls Herd, the ARIA chief executive.

“Those kinds of meetings are unusual in any industry, I think. Everybody was there with the absolute best of intentions, from a whole range of different parts of the sector. This was a group that hadn’t come together to discuss these sorts of issues before, so we were finding our way a bit.”

From the discussion was formed a temporary working group of volunteers, all women. “We knew we had to conduct a really widespread consultation process across the industry, and that we needed experts to guide us through that process to make sure we did it properly,” Herd says. “That should be happening fairly soon.”

“But it is extremely difficult and extremely sensitive,” she says. “We have to be very careful to be survivor-centric and to not re-traumatise people who’ve already been through incredibly difficult situations. There’s nothing easy about this.”

-

If there’s a single thread that connects all of the aforementioned events, it’s the behaviour of men.

Whether it’s men’s poor behaviour, or men being complicit in the poor behaviour of their peers through a lack of meaningful action or accountability, it is clear that a dearth of women in senior leadership roles in Australia’s recorded music industry has led to some devastating outcomes.

As far as Sony Music Australia is concerned, October 11 was a black day in the company’s history. That night, ABC TV program Four Corners aired its investigation into Sony’s toxic corporate culture under Denis Handlin.

On national television, former employees dating back to the 1980s claimed that Sony’s win-at-all-costs credo resulted in bullying, harassment and alcohol abuse.

The seriousness of these allegations, combined with the credibility of the former employees who appeared on camera, prompted music industry organisations including APRA AMCOS, ARIA and QMusic to strip Handlin of honorary accolades he had received in 2009, 2014 and 2020, respectively.

In a statement issued the day after Four Corners aired, the Queensland music industry body QMusic said, “Following ongoing reports of systemic bullying, discrimination, and misconduct under Handlin’s leadership, we cannot let QMusic’s acknowledgment and celebration of his career stand.

“Toxic workplaces, be they in the office, boardroom, on stage or behind, have no future in Australian music. We cannot, and should not accept nor celebrate this culture. The future of music must be one that is safe, supportive, and equitable for all.”

Recording artists signed to Sony have generally kept their mouths shut, both since Handlin’s removal in June and Four Corners last month. While some see this blanket silence as a straightforward failing on these artists’ part, the truth is more complicated.

Senior industry sources tell Review that the goodwill benefits of speaking out against the old regimen under Handlin are outweighed by the potential costs of biting the hand that feeds.

Adverse comments could see the marketing tap for any future music releases turned off entirely, which would seriously affect an artist’s earning potential. Recording careers could also be left to wither on the vine, so to speak, if an artist were to openly denigrate the company that funds their work.

The one and only current Sony recording artist to speak on these matters is one of the label’s best-selling acts.

In a recent interview with Review, Midnight Oil singer Peter Garrett was asked whether it had been hard to bite his tongue on all things Sony of late.

“Well, we were never mistreated by anyone at Sony and we didn’t see any of that behaviour,” Garrett says. “It goes without saying that we oppose bullying, any form, anywhere. So for those company staff that have spoken up, and whether they’re people that were there before or those [there] at the moment, we would strongly support them.

“We would say pretty clearly that the behaviour was inexcusable, and that Sony New York needs to step up,” Garrett continues.

“They were aware, it turns out, of what was happening. They need to support their staff, but also they need to do something serious. I think they’ve got some sort of investigation underway, but they need to take responsibility for their governance failures.”

Midnight Oil has worked with Sony and its subsidiary labels for 40 years, since its third album Place Without a Postcard was released by CBS in 1981. Its upcoming 13th album, due next year, will also be released by Sony.

Across the decades, the Sydney rock band has become well known for encouraging progressive change on matters of environmental conservation and Indigenous reconciliation, among many other subjects. Does Garrett see the recent revelations concerning Sony as positive, progressive steps for the Australian music industry overall?

“I hope so,” he replies. “I think that the industry’s attitude to women in the past, and even up to the present, has in many instances been very poor. There’s a lot of implicit misogyny in some of the songs that people have written in time, and occasionally still do, write.”

“I mean, you’re talking to a band that takes human rights – and the rights of individuals to be treated fairly and with respect – very seriously,” Garrett says. “It is healthy for this to start happening, and the hope is that it’ll turn into meaningful changes of attitude for all concerned.”

Righting the industry’s wrongs has been a priority for Vicki Gordon, the former ARIA board director who established the Australian Women in Music Awards (AWMAs), an event which debuted in Brisbane in October 2018.

“That was absolutely terrifying, because I knew in my heart that it was going to be something that rocked the industry,” Gordon tells Review. “It could have gone either way: it could have been a very positive experience, or it could have been a very negative experience.”

“If you speak with anybody that pioneered change in any industry, it can be very lonely and very frightening,” she says. “That’s why it takes a long time for change to happen, because you’ve just got to have enormous conviction to be able to do it – and not everybody has that.”

This year’s planned AWMAs were postponed to May 2022 due to the pandemic.

Given her experiences setting up an event designed to highlight music industry workers who had been often overlooked for their moment in the spotlight, Gordon is cheering on the positive steps that have been taken this year, particularly at ARIA.

“If there was ever going to be a time and an opportunity to create real change, now is the time,” Gordon says.

“And if there was ever going to be a good time for two women to lead that change [at ARIA], I think now is the time.”

In a seismic year for the Australian music industry, it’s worth bearing in mind that earthquakes are not isolated incidents. Aftershocks are common, and those structures without sturdy, future-proofed foundations may yet crumble.

But what do people tend to do after earthquakes? We learn from our past mistakes, and we rebuild.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout