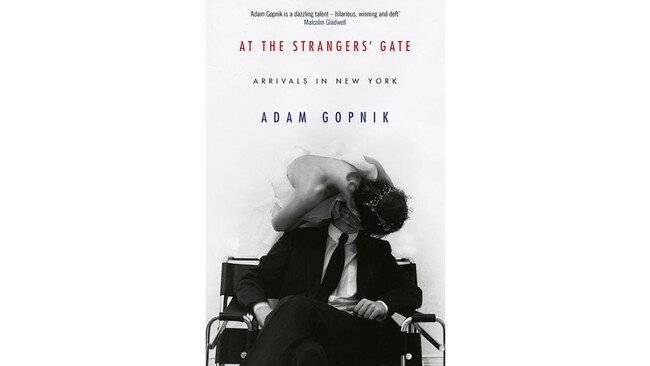

At the Strangers’ Gate: Arrivals in New York, Adam Gopnik’s amusing journey

Adam Gopnik’s At the Strangers’ Gate celebrates his once-naive passion for New York, his wife, his work, and his life.

When Adam Gopnik moved from Montreal to Manhattan at the age of 23, his aim was “to become some odd amalgam of EB White and Lorenz Hart, writing wry essays with one hand and witty lyrics with the other”.

In his own way he has achieved that and At the Strangers’ Gate, his memoir of the 1980s, celebrates his once-naive passion for his city, his wife, his work and his life.

Gopnik’s story reminded me at times of Beautiful, the musical about the rise of songwriter Carole King and her husband a generation earlier, and not only because beautiful is his favourite adjective.

Gopnik and his wife, Martha Parker — “the prettiest girl I’d ever seen” — arrived in New York City newly married in 1980, with no money but more than enough talent, ambition and chutzpah. They danced through a decade of soaring wealth, art as commodity, food as art and shopping as recreation. You can almost hear the soundtrack.

He had a scholarship to study art history, she was learning to edit documentaries.

In their tiny, cockroach-infested apartment on the Upper East Side, they vowed to live with beautiful things, to seek poetry and fantasy above normalcy and realism. That attitude might be cloying, except that Gopnik is also a muscular, observant, self-deprecating and funny writer whose persistence eventually won him a staff job on The New Yorker, where he is now an elder.

I’ve been reading Gopnik for 30 years, since my arrival in New York in the late 80s, when he was an art critic and beginning to write long cultural essays for the magazine. I admired — and still do — his ability to combine the personal and the intellectual, to use an anecdote to illustrate an epoch.

When he and Martha and their son moved to Paris in the mid-90s, I followed his explorations of French society and made a pilgrimage to the Glass House, a 30s house on the Left Bank that obsessed Gopnik. When they returned to New York after I had left, I appreciated the new perspective family life gave him.

To my surprise, Renata Adler, another of my spiritual guides to New York, attacked Gopnik in her 1999 book Gone, about the perceived decline of The New Yorker in the previous decade.

Adler saw the new employee as a self-serving sycophant “who embodies certain lamentably ascendant qualities of his time”. The brittle older writer had her own problems and I wondered if her savage portrait of the upstart was a symptom of generational handover.

This is the young Gopnik that the older Gopnik reflects on in At the Strangers’ Gate and indeed, consciously and unconsciously, there is something of the arriviste in his self-portrait.

“Forty years is the natural gestation time of nostalgia,” he writes to explain the why and how of the book. So there is romance, but also humour, in his “sort-of” jobs, cataloguing dead artists at the Frick Library, lecturing at the Museum of Modern Art, while studying and learning to write, mostly into a void.

His first real job was as an editor at men’s fashion magazine GQ, and things looked up after he met famed photographer Richard Avedon, “who became our surrogate father, a best friend, a mentor of a kind … our introduction to the world of power and glamour in New York and, in another way, the source of our first disillusion with those things”.

His sketches of Avedon and another mentor-friend, Australian art critic Robert Hughes, are clever and precise.

A walk with Avedon in Central Park turns into a comic fantasy when the older man organises an impromptu photo shoot with two passing women who have no idea who he is.

Hughes was “one of those people who can achieve the effect of a debating team at table while sitting alone” and “had come to hate, rather than merely discriminate among, the current generation of artists”.

The essays in the first half of the book mostly began life in The New Yorker or as spoken pieces for non-profit storytelling group The Moth, and show Gopnik’s delight in performance: a lost pair of trousers from an expensive suit becomes a symbol of the couple’s search for beauty; an argument with Martha about undercooked tuna was set in 2006 for The Moth but here takes place in the 80s. His flamboyant sentences build and turn on themselves to rhetorical effect.

Part two follows their move in 1983 to a SoHo loft and from the cocoon of love into public life. An incisive essay on the downtown art scene, drawing on the work Gopnik did for MoMA’s High and Low exhibition in 1990, pits Hughes against artist Jeff Koons as old and new, “pre-ironic” v “the first embodiment of post-ironic man, enraptured by the outre and so enwrapped in the mannered that he couldn’t know it as such”.

There are shadows over the rom-com: the loft was infested with mice and “super-rats”; AIDS ravaged the city; but worst, Gopnik suggests, was the “very last dinner party of the period”, held by an art dealer for a billionaire who was going to prison the next day.

All the “nastier elements of the 80s did seem to have condensed into one storm cloud that night”.

Gopnik’s New York is recognisable for those of us who were there, and entertaining even if you weren’t. He is insightful and amusing.

By the end, though, as he and Martha prepare to escape the city’s decadence, he sounds remarkably like his old colleague Adler, a jaded prophet of the end of his era.

Susan Wyndham was a New York correspondent for The Australian from 1988 to 1996.

At the Strangers’ Gate: Arrivals in New York

By Adam Gopnik

Riverrun, 253pp, $32.99