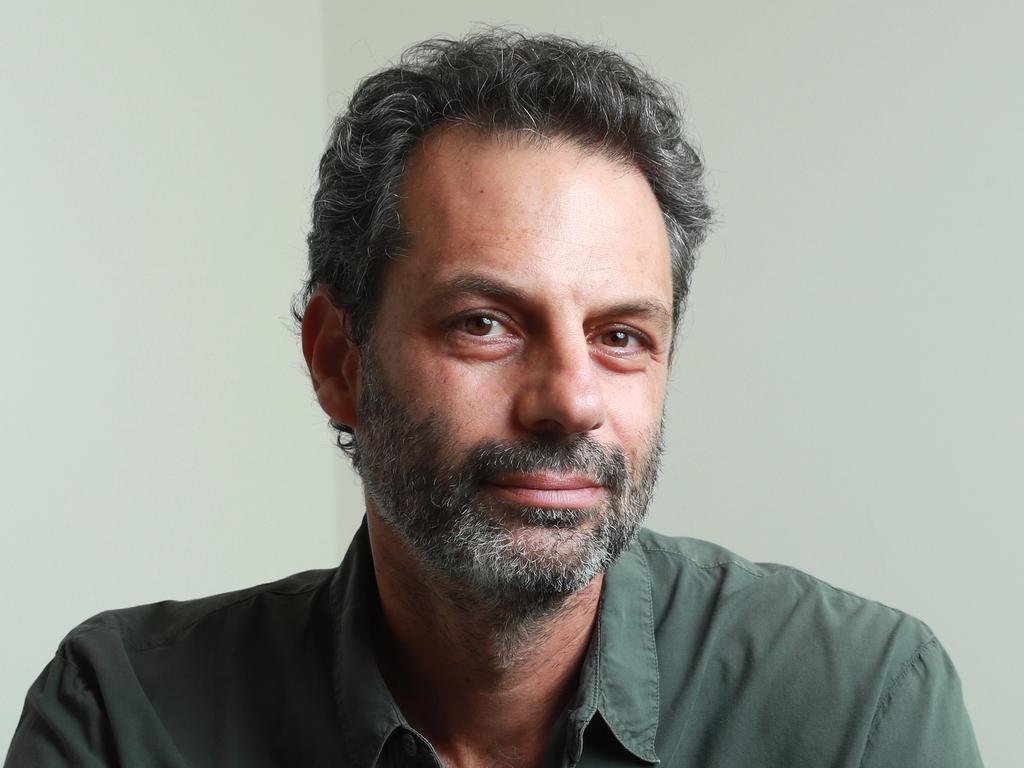

Arts Minister Tony Burke’s first policy riff met with generous applause

New Arts Minister Tony Burke has left nothing to chance with his first national cultural policy, gearing it squarely towards the commercial and popular and offering a roadmap the creative sector has been demanding for years.

Tony Burke must be having a feeling of deja vu. He was a junior political staffer in Canberra in 1994 when Paul Keating launched his Creative Nation cultural policy at the National Gallery of Australia. Then, in 2013, he inherited the rollout of Labor’s Creative Australia policy in the few months between Simon Crean being dropped from the Gillard ministry and Rudd losing the election that year.

With Labor’s third iteration of a cultural policy, and the first with his name on it, Burke has left nothing to chance. Burke, 53, is known as the guitar-playing arts minister. He reads a poem every day. Last July he began a period of consultation and town hall-style meetings and promised to have a cultural policy out by close of business, 2022. He delivered his policy document, called Revive, on Monday – a month after deadline.

Compared with Labor’s previous, short-lived ventures in the cultural policy arena, this one looks as though it has staying power. The Albanese government is in the first year of its first term and what will possibly extend to a second. Burke may be reasonably confident that his glossy Revive booklets – “Australia’s cultural policy for the next five years”, printed on the slippery paper stock of government documents – won’t get dusty on the shelf or be consigned to the garbage so soon.

In the main, it’s a creative industries strategy, geared towards the commercial or popular side of the arts, dressed in the language of cultural agency, nationhood and reconciliation, and refreshingly light on the economic cost-benefits of government spending on the arts, in this case $286m across four years. The outlay is comparable, in real-dollar terms, to Crean’s Creative Australia ($235m), but doesn’t quite match Keating’s $250m splash with Creative Nation in 1994 ($512m in today’s money).

The priorities are First Nations arts, Australian contemporary (rock and pop) music, Australian writers and books, artists’ livelihoods and safety, and Australian films and TV where many people watch them – on their streaming platforms.

Burke says his strategy is about putting the creative sector on a secure footing after 10 years of policy drift under the Coalition and the hammering of the pandemic. So what should the nation’s cultural life look like in year five of Revive?

“We should no longer feel that we are coming out of lockdowns,” he tells Review. “Were it not for Covid, I would have intended to have a cultural policy that could last longer. The sector is in such a state of flux, there is a whole lot that is changing rapidly. I took the view that we needed to make some structural changes and look at the commercial world in ways that we previously hadn’t. Then to get a bit of momentum and to review again.”

The policy launch is taking place at the Esplanade Hotel, the storied live-music venue on the waterfront in St Kilda. Its shabby-chic Gershwin Room has played host in years gone by to the likes of Paul Kelly, Beasts of Bourbon, Jenny Morris and many more. Today, the room is shoulder to shoulder with arts managers, politicians, policy wonks, some well-suited philanthropists and a handful of bona fide artists to hear what Burke and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese have to say about Australia’s cultural future. Soprano Deborah Cheetham, accompanied by string players from the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, sings her welcome-to-country composition, Long Time Living Here. At the end, Missy Higgins will come on stage to sing the Triffids’ Wide Open Road.

“The Espy is my sort of posh,” Burke tells the 300 or so guests. “I did prefer it back in the days when your feet did, in fact, stick to the carpet.

“But holding the launch here, it’s a reminder that arts and entertainment is for everyone. Whether you’re reading a thriller, a history or a poem. Whether you’re watching from formal allocated seating or from a mosh pit. Whether you view art from a gallery or in a back lane from the side of a wall, our artists work for all of us, and their works reach all of us.”

He ticks off the policy’s main points. The Australia Council will be reborn as Creative Australia, and the Brandis cuts – money that Coalition arts minister George Brandis redirected from the funding body in 2015 – will be returned in full. Two industry-focused bodies will be set up within Creative Australia for contemporary music and books. There will be a poet laureate, a development fund for digital games, more money for regional arts, disability arts, health and education programs.

It’s all well received, but even as the crowd listens attentively, the murmurs start. A well-known arts figure, standing next to me, gives a nudge and whispers, “What about the visual arts?” Another long-time arts manager says something similar: “Where in this policy is theatre?”

Later, I’ll do a digital search of the policy booklet. Opera, ballet and classical music are mentioned only in passing. Renowned companies that used to be called the “majors” – such as Opera Australia, the Australian Ballet and the Australian Chamber Orchestra – are nowhere to be seen. Sophie Galaise, managing director of the MSO whose musicians have just played for the launch, says she doesn’t regard the omission as a slight.

“We are hoping that the major performing arts organisations will not be forgotten and we are very excited and happy to see funding come back to small and medium organisations,” she says. “This is so important, the ecology of the music sector and the arts. To see it rebalance will be thrilling and great.”

Nick Mitzevich, director of the National Gallery of Australia, is buzzing that the gallery will receive $11.8m to share its collection with suburban and regional arts centres, but he’ll have to wait for the $265m the NGA needs to fix its Canberra building.

“I’m very optimistic,” he says. “Our expectations are working with the government for the May budget. We are so pleased to see the start of a very optimistic future for the cultural sector, and this is the first step.”

Once the official proceedings are over, I’m ushered upstairs to a quieter room at the Espy for an audience with the arts minister. Up here the carpet is not sticky and there’s an overpowering smell of incense. Burke is sitting on a sofa in a corner of the room and I ask him why the traditional performing arts – still in command of the larger part of government subsidy – are absent from his vision for Australia’s cultural future. The emphasis seems to be on the more popular and commercial genres of rock music, TV and video games.

“Importantly, we have been able to do these new areas without cutting any of the others,” he says. “And that’s very telling. The way arts policy was run over the past decade, there would be an opportunity for a culture war against the elites, or something like that. We haven’t done that. There is no section that has been punished in order for us to reach more people.”

The cornerstone of Burke’s policy is a regearing of the Australia Council, to be renamed Creative Australia.

While the council has research and advisory functions, its main purpose has been to distribute almost $200m a year in government grants – to independent artists, small companies and the majors – where funding decisions are made under the principles of peer review and at arm’s length from government.

Creative Australia will have an expanded remit to include the commercial and philanthropic sectors, with a funding boost of $199m across four years. The largest parcel ($69.4m) is for a new body, Music Australia, which will promote contemporary music through industry partnerships, skills development and export markets. It will be enacted by legislation and funding will begin in July. A second body for the books and literature sector, Writers Australia ($19.3m), will come online from 2025. It will decide on the appointment of a poet laureate, and judge the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards. A new pool of funds ($19m) will be available for the commissioning of new Australian works of scale.

The policy also establishes a dedicated, First Nations-led board ($35.5m), providing funds for new artworks, skills development and best practice on cultural protocols and safety. It aligns with the priority given to First Nations art and artists in the cultural policy. The measures include a fund to develop a First Nations languages partnership ($11m) and legislation to protect Indigenous artists from fake art and souvenirs ($13.4m). Other commitments, already announced, contribute to major new Aboriginal galleries in Alice Springs ($80m) and Perth ($50m).

The new Centre for Arts and Entertainment Workplaces is intended to help wipe out harassment and bullying in the industry ($8.1m) and Creative Australia will also assume the responsibilities of Creative Partnerships Australia, the body that promotes private-sector support for the arts through sponsorships and philanthropy.

Burke says Creative Australia is intended to bring into the one organisation the three main strands of creative production – the subsidised sector, the commercial, and the philanthropic – even though he acknowledges each operates differently. As stated in the Revive policy booklet, Music Australia and Writing Australia are designed to reach into those commercial sectors where traditional grants funding has had limited success. Burke says these new bodies will help address the structural challenges in those industries brought about by technology and changing markets.

“If you are a contemporary musician, you used to get a good enough income from your album sales, your merch sales, and your performances,” he says. “For so many people now, the album sales have completely collapsed … Streaming, as a method of income, really only works if you can build yourself a significant national audience. That’s one of the things that Music Australia money will do; how do you get a bigger reach in North America and get yourself on the bill there?

“If you can have strategic work from government in building those markets, you change the capacity of our artists to be able to make a good living.”

The Centre for Arts and Entertainment Workplaces has become necessary, he says, because of documented abuses in parts of the industry where there is potential for exploitation. Burke says the centre will have the capacity to provide evidence of abuse to other government departments. He declines to name a minimum wage for artists, saying that artists’ pay will be considered in the context of his review of modern awards.

“What we are trying to do is establish the structural means (through the Centre for Arts and Entertainment Workplaces) to be able to arrive at those sorts of decisions,” he says. “As part of the review of modern awards that I’m doing in the workplace relations portfolio, it will be reviewing specifically the impacts on arts workers, including visual artists.”

Similarly, Burke has not yet named an Australian content quota to be applied to the global streaming giants including Netflix, Amazon Prime and Disney+, but he has named a date. Rules that require streaming platforms to show a prescribed minimum of Australian content will come into force on July 1 next year, after a period of industry consultation. Screen Producers Australia argues that 20 per cent of revenues earnt by the streaming platforms in Australia be reinvested in Australian shows. A sticking point is likely to be what constitutes Australian content, but Burke is adamant that more be available.

“If you feel like watching something from your own country, and you go through the menus on some of these streaming services, and there’s just nothing (it’s disappointing),” he says. “When they have a go, they produce real quality content. I just want there to be more of it.”

Burke’s plans will be guided into action by a national cultural policy steering committee, and the policy will be evaluated and renewed after three years. That’s a surety, as much as can be given, that Revive will be no one-hit wonder, but a road map for industry growth and development into the near future.

It’s what the creative sector has been demanding for years.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout