Artist Ben Quilty on his Bali Nine friend and student Myuran Sukumaran

Ben Quilty’s relationship with condemned Bali Nine prisoner Myuran Sukumaran went from teacher to heartbroken friend.

On November 10, 2012, three days after Julia Gillard flew to Bali to chair a democracy forum with her Indonesian counterpart Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, Mary Farrow went on Facebook to send a message to the Australian artist Ben Quilty. Farrow was a supporter of Myuran Sukumaran, the Bali Nine drug smuggler who had applied for presidential clemency four months earlier. Sukumaran, then 31, was facing death. His application said he had been “working to better himself” behind bars.

Farrow didn’t know Quilty personally, but had seen his Archibald Prize-winning portrait of Margaret Olley and thought she’d try her luck. So she explained how Sukumaran had taken up painting at Indonesia’s Kerobokan Prison, and how it was the “challenge of a lifetime”. He was going to enter a portrait of his lawyer, Julian McMahon, into the Archibald, even though he wouldn’t be eligible because he hadn’t lived in Australia during the previous 12 months. He had, of course, been locked up in Kerobokan since his arrest in 2005. Sukumaran had found “peace and salvation” in art, Fallow said, but he needed some “constructive advice”. “Could that be you or someone you know?”

A few days later, Quilty sent a message back: “I will help.”

■ ■ ■ ■

Were it not for the Bali Nine, Quilty may never have travelled to Bali. Based in the NSW southern highlands, his adventures abroad tend to follow a certain pattern. In 2003, he travelled to Paris after winning the Brett Whiteley Travelling Art Scholarship. In 2007, he spent four months in Spain on an Australia Council residency. Four years later he found himself working in Afghanistan, an official war artist for the Australian War Memorial. And earlier this year he joined Richard Flanagan in Lebanon, Greece and Serbia, documenting the exodus of Syrian refugees. But Bali? It wasn’t his thing. “It’s not for me to go to a Third World country and get massages,” Quilty says. “Never has been.”

That Facebook message, though, had made Quilty curious. Like so many others in Australia, he had followed the case of the Bali Nine as it played out in front of the cameras. The fate of the nine young Australians had seemed inevitable from the moment of their arrest in April 2005, trying to smuggle heroin out of Indonesia. Denpansar judges handed down their sentences less than a year later. While seven of the nine were ordered to spend the rest of their lives behind bars, a harsher sentence awaited the pair seen to have leadership roles: death by firing squad for Sukumaran, the “enforcer”, along with his friend, the “godfather” Andrew Chan.

For Quilty, there was something else that caught his attention. It’s common for artists who have achieved success to be pestered for advice, and he usually recommends a combination of hard work and art school. In this instance, though, there were encouraging signs. Sukumaran was also especially hungry to learn. He was interested in “thick paint”, and this resonated with Quilty, himself an impasto specialist.

“That’s why I engaged,” he says. “The questions he asked very clearly showed that he’d made some progress and that he’d tried, and I thought it was just so remarkable that someone in that circumstance was trying. It was also against the notion that I had of him. I’d only heard the press of him being this evil monster, the enforcer. So I just decided to go there and meet him.”

More than 18 months have now passed since Sukumaran’s execution, and Quilty still stirs with passion and anger about the loss of his friend. As he looks back on those transformative years, recalling all the highs and the terrible lows, there’s also a distinct sense of admiration for Sukumaran’s achievements and character — especially now, on the eve of a new exhibition in Sydney dedicated to the work of a man who entered prison as a criminal and left it as an artist. “It’s a refuge,” Quilty says. “For me, that’s what art is.”

■ ■ ■ ■

Back in late 2012, after she received Quilty’s promise to help, Farrow let Sukumaran know the good news. He was excited to have such a distinguished mentor: “I’ll check my schedule but I’m pretty sure I’m available whenever he has the time!”

Quilty flew to Bali. He made his way past the airport drug warnings and the crowds on Kuta Beach to Kerobokan, where he found Sukumaran immersed in gossip magazines. The prisoner had been painting pictures of celebrities for “ghoulish Westerners” at local markets.

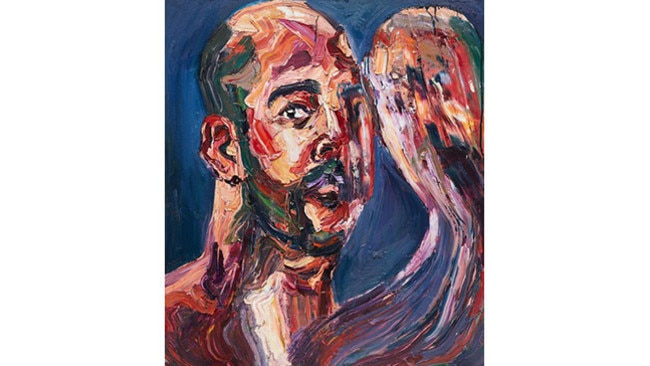

Obviously this wouldn’t do. Quilty told Sukumaran he should “turn the mirror” on himself if he was serious about improving. The first lesson was to paint self-portraits: “It addresses all the questions that the public in Australia has about who you actually are and who you’ve become. It’s also better for practice.”

“That’s what I did years ago,” Quilty says, “and it was just obvious that he should do it. He wanted to work at night when he was locked up. You can have a mirror and art materials and not break the rules of the prison and continue working as late as you want.”

Quilty assigned a self-portrait a day. Sukumaran worked quickly, creating more than 20 in a fortnight. In addition to his talent — a real facility was already apparent — Quilty could see his student was willing to put in the effort, too.

The lessons continued, with additional workshops run by Melbourne artist Matthew Sleeth. Quilty took over materials, mostly paint, and helped Sukumaran source locally whatever he needed to work. He also gave him art books. Quilty is similar to many artists in that he only ever flicks through the dozens of art books that line his shelves. Sukumaran, by contrast, devoured them all, cover to cover. “It was unreal,” Quilty says. “He was so hungry to learn.”

In September 2014, the first exhibition of Sukumaran’s work opened in Australia. It was held at Sleeth’s Melbourne studio, and timed to coincide with the end of Yudhoyono’s term in office. (Sleeth, now making a film about the saga, remains a great admirer of Sukumaran: “There’s nothing more optimistic about wanting to be a better artist on death row.”) The 28 paintings in the show were all portraits, and they depicted politicians from Australia and Indonesia, fellow prisoners and, of course, the artist himself. They raised $14,000 for the construction of a gallery space at the prison.

Sukumaran was maturing as an artist but time was running out. In February last year, Curtin University awarded him an associate degree in fine art. Quilty broke the news on Twitter: “I am one immensely proud friend.”

By this point, the end was in sight, and Quilty was making regular trips to Indonesia. His relationship with Sukumaran was also evolving. For three years, their conversations had been largely about art — “he didn’t want to waste any time” — but now Sukumaran was opening up.

Then at 6am on March 4, five days after Quilty’s tweet about Curtin University, Sukumaran and Chan were led away from Kerobokan for the final time. They were taken to Nusakambangan island for execution.

Once there, Sukumaran and Chan shared a cell for the first time in years. They had been friends since their teens, but had fallen out soon after their arrest. Since then, they had found peace in their own ways: Sukumaran with art, Chan with god.

They had long since re-established their friendship too — but these were difficult circumstances, and they began to argue again inside their cell. The reason? Sukumaran wouldn’t stop painting. He was working into the early hours of the morning, prompting Chan to complain “the fumes” were going to kill him.

They reconciled the next day, laughing about the nature of their argument. Sukumaran, as always, kept painting. His progress as an artist had consistently contained an urgent message — among his supporters, this had been a determined campaign to reveal the authenticity of his rehabilitation — but now all that was left was the art. The day before his execution, he spoke to Quilty on the phone and sounded upbeat. “He said he was painting, said that he had made the best paintings of his life in the last 48 hours, and that he was going to paint that night again.” He also mentioned that he and Chan were teaching the other prisoners to sing Amazing Grace.

■ ■ ■ ■

The new show, part of the Sydney Festival, is called Another Day in Paradise. It’s been curated by Quilty and Michael Dagostino, director of the Campbelltown Arts Centre, and includes work seen at Sleeth’s studio in 2014. There are 120 paintings by Sukumaran created either in Kerobokan or Nusakambangan. Quilty sketched Sukumaran many times, but his own pictures are not included. Instead six other artists have been invited to present art that deals with the death penalty and human rights.

By its nature, the show is highly political. It also tells the story of personal renewal as Sukumaran details his fate: Time is Ticking shows the artist with a hole over his heart while other paintings focus on a single bullet, a cross, a human heart and an Indonesian flag, the latter two signed by all the prisoners on death row.

The self-portraits are full of emotion, at once raw and vulnerable, muscular and calm. It’s easy to see the presence of the teacher in them too. There are differences, especially in their anguished, surreal moments, but they share a common touch, those broad strokes and thick paint that have won Quilty so much acclaim over the years. Quilty sees this as inevitable, given their intensive, one-on-one tuition. If only there had been more time, he says, then the student would soon have painted his way through the teacher to find his own style.

“We were starting discussions about exactly that,” he says. “He was at that point of needing me to start showing him how to find his own language.”

Quilty is confident the paintings are powerful even without context. But he knows that the art can’t be separated from his life. “Of course they’re informed by their story,” he says.

It brings to mind an exhibition now showing at the Art Gallery of South Australia, Sappers and Shrapnel, in which Quilty and others respond to wartime debris known as trench art. “What brings people to make and create? What happiness or sadness or horror or tragedy in the human condition is it that drives the creative urge? For Myuran, yes, it’s instinctively linked to his situation.”

■ ■ ■ ■

There’s an unfinished painting in Quilty’s studio that shows an otherworldly dinner scene with a grotesque group of characters huddled around a table. The idea invokes the failings of democracy and leadership, a Last Supper-style reflection about members of the political elite who sit around while the world descends into “chaotic, insane, drug-addled madness”.

On the other side of the room he has stacked children’s life vests from Lesbos, with paintings of them hanging on the wall nearby. Other spaces are filled with canvases by him and by Sukumaran. And scattered among the papers on his desk are documents from the Art Gallery of NSW, where Quilty has been a trustee since January 2013.

“Margaret Olley used to hammer me about taking on causes,” Quilty says. In those early days, still finding his feet as a painter, he was fascinated by ideas of masculinity and rites of passage. Olley considered these issues a distraction, but Quilty felt differently.

“It really annoyed her that I engaged in causes,” he says. “She said I shouldn’t be taking these on, that beauty should be at the centre of your creative process. I don’t agree with that. I wasn’t that forthright with Margaret, but I just don’t agree with it.”

Quilty has proved to be such a forceful, articulate figure in Sukumaran’s campaign that it’s easy to forget he came on board only by chance. Some of the other artistic or political figures involved adopted a lower profile to ensure the message stayed focused. And as the spotlight fell on Quilty, he attracted unwanted attention too, including death threats. These messages were serious — “very angry, aggressive, psychotic threats” — but he felt they paled in comparison with events in Indonesia. “It’s funny,” he says. “You cop public criticism if you have a public stance on anything in Australia.”

He’d love to tour the new show, especially to a country that still uses the death penalty. But the past four years have been tough. “It’s the ugliest thing I’ve ever been through. No doubt about it. And I hope that I never go through anything like that again. Just the injustice of it. The stupidity of it. The political involvement.

“Myuran was very aware of it. He was speaking fluent Indonesian. He understood the way the whole political system worked. It was in his interests to understand it, and that’s one of the admirable things about him.

“He wanted to understand everything so that he could face it with some sanity. And to be back here and to watch it happen was just horrendous.”

Myuran Sukumaran: Another Day in Paradise is at the Campbelltown Arts Centre as part of the Sydney Festival from January 13 to March 26.