Arthur Upfield created part-indigenous detective Bony and loved the outback

A just-published autobiography of Arthur Upfield, creator of part-indigenous detective Bony, shows that sometimes outsiders have the clearest perspective.

“Nurse and tutor of eccentric minds, home of the weird’’: the grand Australian bush of Henry Lawson’s imagining was a place of radical difference — a mindscape as much as a landscape, and one whose effects varied according to the individual.

Where others saw an endless monotony of stunted scrub or rust red sandhills, Lawson felt the bush as a goad, a drug, a strong attractor. It urged him to travel ever deeper in to its red heart.

Arthur William Upfield (1890-1964), the scapegrace son of a Hampshire draper who was sent to Australia as a young man, came to revere Lawson.

He too suffered from the poet’s addiction: not to booze, though he liked a drink, but to the outback, to what he called ‘‘Australia Proper’’.

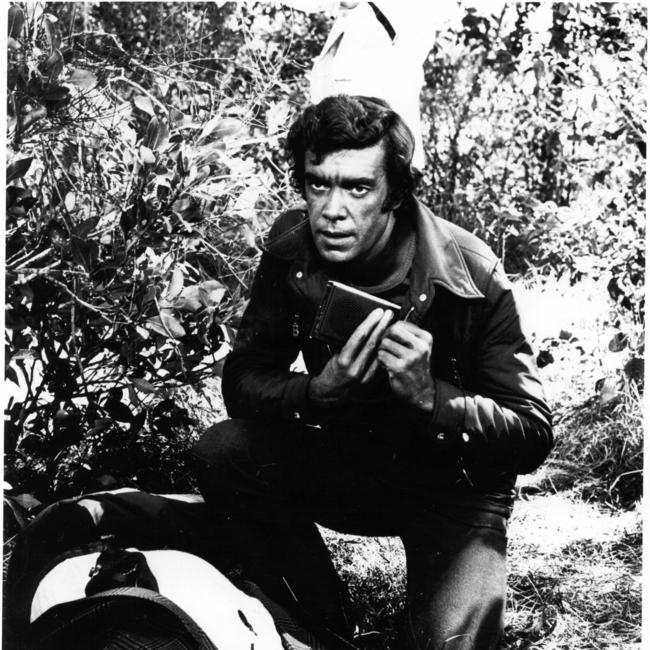

Which makes it unsurprising that Upfield’s autobiography, completed by the author before World War II but only now published, is a record of people and place as much as the account of that intrepid, energetic, odd-jobbing bushman who became a globally successful crime writer: creator of the poised and subtle part-indigenous detective Napoleon ‘‘Bony’’ Bonaparte. (The 1970s TV series, starring New Zealand actor James Laurenson, was called Boney).

Upfield’s first encounter with the bush came soon after arriving in Adelaide in 1911, when he landed a job working for a German immigrant farmer in the Murray Mallee region near the Victorian border.

Having been prepared by the immigration literature for a land of lush pastures, glossy cows and rose-clad cottages, he discovered a dusty expanse and a homestead built of hessian stretched over a bush frame. His own quarters consisted of ‘‘a 2000 gallon rain tank turned upside down’’, with a hole cut for a door.

The position didn’t last but Upfield’s appetite for further travel inland was whetted. Next chance he got, the 21-year-old blagged his way into a boundary riders’ job, despite being manifestly short-skilled for the role: ‘‘The jumbled hills of the Barrier Range were my first glimpse of the Australia which was to become the passion of my life. Broken Hill was then in its hey-day, but I saw little of it, for I arrived at 8 o’clock, and left for Wilcannia, on the Darling, on the box of a Cobb & Co coach.’’

His destination, Tearle Station in north-western NSW, was to be the undergraduate campus of Upfield’s bush education. It is a world he recalls with the fond avidity of a man aware it will soon be lost.

Before the motor car, before the terrible rupture of World War I, before the inland population leached to coastal margin, before the White Australia policy hardened into racial orthodoxy and the indigenous world that preceded Europeans by millennia was forced underground, there existed a vivid, thriving, cosmopolitan Australian frontier: a hard place, to be sure —– the region was constantly threatened by drought, flood, plague or economic upheaval — but one that offered opportunity for employment and adventure. And Upfield embraced it with the earnest zeal of a convert.

First among his professors was a bullocky known as ‘‘One-Spur Dick’’, ‘‘a one-eyed, thick-set, whiskery, sun-blackened man, dressed in a blue shirt and moleskin pants, and wearing but one draggled spur’’, who taught the Englishman (soon to be universally known as ‘‘Hampshire’’) how to drive the teams that served as the road-trains of their era, and much else besides: ‘‘how to bake a damper, how to kill and dress a sheep, how to make horse hobbles, how to ride in the Australian fashion, and how to use my fists.’’

‘‘He demonstrated’’ continues Upfield, ‘‘that neither bullocks nor mules nor horses understood pure English or pure Chinese, but would pull like the devil when addressed in a proper mixture of all the oaths of both nations, topped up, as it were, by the worst oaths favoured by the Afghans.’’

Dick is just one of many eccentrics surveyed in Beyond the Mirage. The Australian outback of the prewar era was, for Upfield, exclusively populated by such outsized characters:

Never before had I met such people; never have I met their like beyond Central Australia. Their language was terrific, saved from crudeness by its artistry. Their leg-pulling was severe; tempers quick, and fists hard. Their hearts were big, their humour dry, and the standard of general knowledge surprisingly high.

If the early chapters of his autobiography are given over to education at the hands of such types, the Great War represents an unwelcome intermission. This book does not mention Upfield’s time as a driver with the Army Service Corps in the Middle East. Nor does it dwell on his experience at Gallipoli, or his time in France afterward. The war is passed over almost without mention, as though a full recounting would grubby the paradisal innocence of its true, antipodean subject.

In passing, it is noted that the author married an Australian nurse in Egypt and had a son. But after a brief post-conflict hiatus in Britain, where Upfield tried and failed once again to join a respectable profession, he returned to Australia, where he left his new family in the city and took up his inland wanderings once again.

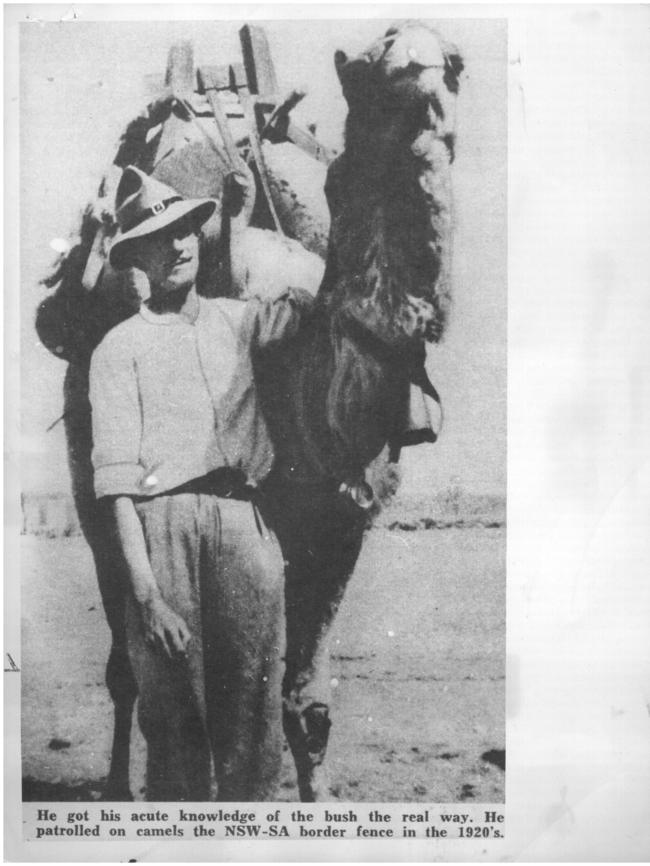

This second period lasts longer and is more melancholy, sometimes haunted. Like his fellow Gallipoli veteran Bert Facey, Upfield sought healing in rural solitude and modest labour. He does not have the vocabulary to describe his trauma, only a sense that working as a mean station cook or repairing sections of the dingo fence with only a troop of camels and a dog named Hool-em-up for company served as a form of therapy.

But between 1914 and 1920, the inland had changed. The truck had replaced the bullock carts and the ranks of splendid eccentrics had been thinned by time and conflict. Upfield found solace in surrendering to wanderlust, though he increasingly felt caught in an ambitionless rut.

Writing and literature, which had been an early passion, became a means to wrest some value from those years of toil.

‘‘Australia Proper’’ and its people were the raw material for the novels that he plotted while fencing or rabbit trapping, or else scribbled down between cooking shifts. And while the autobiography closes before Upfield’s career is fully established, readers can see how the sheer breadth of his understanding of and appreciation for inland Australia became the enduring character that linked his fictions.

Those narratives may have been rough-hewn at times, the prose workaday, but that unquenchable attentiveness to place is what saves his work, lifts if out of its historical moment and the confines of genre. There is one other crucial character, of course — encountered by chance, according to Beyond the Mirage, when Upfield was swagging his way from Wilcannia to Bourke. There he met a part-indigenous man who appeared out of nowhere to share a fire and the following weeks with the Englishman:

[H]is erudition was delightful and never at any time forced on one. His mind was a storehouse of knowledge of the kind obtained by wide reading as well as through observation. He showed me to what height of efficiency a human could rise in the art of tracking: and the wiles that could be used to fault the keenest tracker. He opened my eyes — which I had thought were wide open — to gaze at worlds beyond the mundane, the worlds of the insect, the bird, the animal and the reptile.

The tangled Edwardian syntax is of its time. But the attitudes expressed, of curiosity, respect, even reverence for indigenous knowledge are so thrillingly modern that most of us are yet to catch up with them. As is so often the case, it is the migrant who emerges as the true patriot — and the one to see clearly those things locals can or will not.

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.

Beyond the Mirage: An Autobiography, by Arthur Upfield, ETT Imprint, 280pp, $39.95.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout