Arthur Miller’s legacy endures in The Crucible; Death of a Salesman

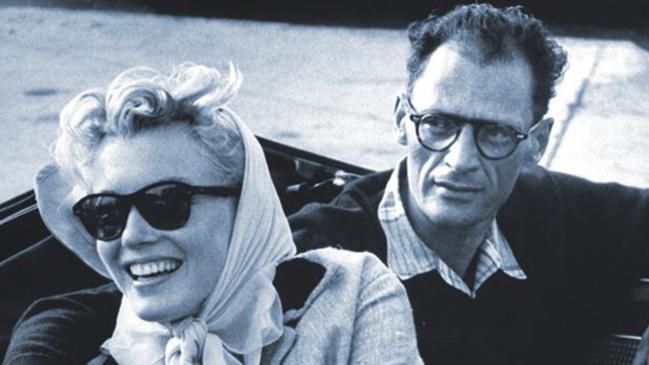

He married Marilyn Monroe and wrote two of America’s greatest plays. Fans of Arthur Miller have plenty to celebrate.

Arthur Miller wrote two of the greatest plays of the modern American theatre and he married Marilyn Monroe. The man who was born 100 years ago this year was a figure who stood at the absolute centre of American culture in the middle of the 20th century and his shadow is going to loom for a long time yet.

It’s not an altogether happy life story nor one of unbroken achievement. Miller, who would see a script of his, The Misfits, made into a film by the great John Huston and starring Monroe opposite Clark Gable, would also see her dead a couple of years later, shattered, sad and — famously to the point of seeming almost mythological — President John F. Kennedy’s mistress.

Miller writes with great eloquence about Monroe in his superb 1987 autobiography, Timebends, and he is utterly believable:

“I confronted the end of her as one might stand watching the sinking sun. When a reporter called asking if I would be attending her funeral in California, the very idea of a burial was outlandish, and stunned as I was, I answered without thinking, ‘She won’t be there’.”

That’s one realisation of personal disaster. And the play that is the greatest ever to be written about American history as a kind of symbolic framework for what could go wrong with American politics, The Crucible, came out of the terrible confusions of McCarthyism and the House Un-American Activities Committee, which saw Miller hauled before that star chamber and asked to name names of communists because he had been some sort of leftie long ago.

In the process it wounded Miller’s relationship with Elia Kazan, who had directed Death of a Salesman on Broadway and who was crucial to the perception of Miller as an instant classic, a kind of latter-day Shakespeare or Ibsen.

So when Sydneysiders were lucky enough to see Death of a Salesman performed in 1982 with Warren Mitchell as Willy Loman (the little man who goes down like King Lear) and the young Mel Gibson as Biff, they knew — a few brief decades after the play was written — they were witnessing one of the greater works of dramatic art the imagination was capable of.

You can see the risky, hyper-rich folk idiom of The Crucible — with Miller creating a vernacular American that never existed linguistically, a bit like Melville in Moby-Dick, a gothic, picture-postcard dream of America concocted out of biblical rhythms — come out of Miller’s early dreams of a classical theatre. And at the same time, they were linked with a Diego Rivera-style sense of the grandeur of the folk.

Whereas Miller just once, in The Crucible, and then riskily, acted out the metaphor of the witch-hunt on a historical canvas that was rich and strange and eerily familiar. He invoked what Harvard critic Harry Levin called — apropos of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Melville and before that, Edgar Allan Poe — the power of blackness.

But before that he had to compose his anthems for common men. The first of these, and still a modern classic, was All My Sons (1947), which David Suchet did on the London stage in 2010 and which I saw performed with considerable power by John Stanton and Janet Andrewartha in a Kate Cherry production in Melbourne in 2007. It’s the story of a man, an ordinary Joe, who sells deficient hardware to the air force which is responsible for the deaths of young men and whose business partner goes to jail while he escapes through mendacity.

It’s a powerful, polyphonic, imperfectly organised play, with a soaring role of sorrow for the actor who plays the wife and mother who won’t accept the death of her son, and a great, shambling, guilt-drenched quiver of evasion — you can imagine what Robert De Niro would have made of the role — for the father who does everything in his power to turn away from tragedy, to blink and flinch and let his gaze flicker but who is caught by it anyway.

It is an “aftermath of World War II” play and perhaps a bit too entangled both in the collective grief of war and Miller’s sense of communitarianism. He said himself the play was centrally flawed by the fact — unbeknown to him — that the air force would have elaborately tested the material anyway.

Still, All My Sons retains its power. It is the first step towards Miller’s recognition that the supposedly common man in modern society has his own claims to tragic heroism; that his capacity for suffering is no less than that of Othello or Oedipus.

Death of a Salesman in 1949 proved this like great cathedral bells that tolled for the kind of American who was liable to be connected to every member of the audience and who did it hard without celebrity or recognition. It followed in the wake of Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie and A Streetcar Named Desire, which seemed to reinvent the idiom of the American theatre and, like them — and the great precursor Eugene O’Neill whose Long Day’s Journey into Night, although written in the early 1940s, was not produced until the mid-50s — it showed the intensity and the striving of life in a democratic, common-garden society. And like Streetcar and All My Sons, Death of a Salesman had the tremendous benefit of Kazan’s direction.

It was Kazan who gave us Marlon Brando’s Stanley Kowalski in Streetcar and just as that performance reinvented modern acting so did Death of a Salesman make the world realise the ordinary and the extraordinary were the two sides of the same coin when it came to the pity and terror of human extremity.

Lee J. Cobb played Willy Loman. Here is Miller’s description of the magical moment when he realised he had a great actor in a great role: “I began to weep myself at some point but was not particularly sad, but it was as much out of pride in our art, in Lee’s magical capacity to imagine, to collect within himself every mote of life since Genesis and to let it pour forth. He stood up there like a giant moving the Rocky Mountains into position.”

Willy Loman is the salesman who is left with no capacity to sell and nothing to earn, like a king dispossessed of his kingdom, which — paradoxically — reflects (or at any rate refracts) the optimism of the postwar moment when American wealth, power and prestige was at some sort of zenith.

But somehow the optimism and the heightened living standards of the period also allowed for the kind of pessimism that is the byproduct of introspection and, more particularly, the sense of the inevitability of tragedy in human life and the supreme preciousness in dramatic art of celebrating the pain of what is endured.

Miller was always obsessed by the theatre of the Greeks and the fact that for all its majesty it was a folk art. A society that can look heartbreak in the face and turn it into art by telling the truth about it is a supremely civilised one.

No one who witnesses the ordeal of Willy Loman can fail to be overwhelmingly moved by this play. I remember seeing it in London in 2006 with Brian Dennehy as Willy Loman and Clare Higgins, that remarkable actress, every inch his equal as Willy’s wife, Linda.

I had known the play since I was a teenager but I was staggered by its power in the hands of actors of the first rank in a superb production by Robert Falls.

Death of a Salesman is the blinding achievement of Arthur Miller’s career.

The Crucible, when it comes in 1953 — at the height of McCarthyism and in the light of Miller being arraigned (and also the shadowplay of his emerging desire for Monroe), is something else again. It’s as different from Salesman as a work could be and that is some indication of its achievement.

Did the costume-drama aspect of The Crucible free Miller to write an allegory that was also an exercise in an enriched rhetoric? Did all those bonnets and Puritan black peaked hats, all that dark romance of old Massachusetts, with its chiaroscuro and its brilliance of blending light and occluded darkness, release a romantic side in Miller that had not been touched by the combination of naturalism and expressionism, the brilliant structural weaving in and out, from past to present (from Willy and Linda in their kitchen, to Biff and Happy in their bedroom) in Salesman?

And The Crucible is a tremendous bit of costume drama (one that almost hungers for the screen) at the same time that it is overtly such a powerful critique of that aspect of American civilisation that could not only look crazy but could seem to as practised an eye as Thomas Mann’s at the edge of fascism or some mutated totalitarianism. But the play has a weird ambivalence that does not lessen the heroism of Proctor or his wife but which susurrates like a great black kind of tradition through all those parts of the play that remain vivid still, long after the horrors of senator Joe McCarthy.

Miller was appalled when someone wrote to him praising his presentation of the reality of actual witchcraft, and (though he thought his correspondent was mad) he got a tiny, uncanny inkling of the feasibility of the delusion.

What is not in doubt, though some people would think it’s a delusion, is the romantic nature of the rhetoric in which the play is cast.

Abigail can threaten: “I will come to you in the black of some terrible night, and I will bring with me a pointy reckoning that will shudder you! And you know I can do it. I saw Indians smash my dear parents’ heads on the pillow next to mine. And I have seen some reddish work done at night. And I can make you wish you had never seen the sun go down!”

And there is the thundering eloquence, no less thundering for being excruciated, of Proctor’s own language: “Peace. It is a providence, and no great change; we are only what we always were, but naked now. Aye, naked! And the wind, God’s icy wind, will blow!”

Miller brings his constructed ye olde American language alive because of the formal intensity with which he projects it on to the deadly dialectic of the devil-versus-decency debate in which every face is a mask for its opposite.

At one level, The Crucible is a popularisation of one kind of classic fiction, the plum pudding and poison poeticism of Hawthorne and Melville, but in effecting this — and it’s a tremendous act of animating a form of artifice — he has created a diction it is impossible for us not to imagine as the voice of late 17th-century Salem, a voice that echoes deep in our memories as weirdly true.

So The Crucible is an extraordinary black magic trick to play on history and a stunning move on the political chessboard. It is one of the greatest acts of liberal propaganda in the history of the world. And it is also, thank God, a remarkable play.

So too is A View from the Bridge (1955), which was done with great success in New York in 1997 with Australia’s Anthony LaPaglia. It was also directed powerfully by Ivo van Hove only this year at Britain’s Young Vic, with a towering performance from Mark Strong as the Italian-American who comes over all unnecessary at his young niece, and Nicola Walker (Ruth in TV’s Spooks) steady as a rock as his wife. It showed how Miller remained powerful — and in touch with that folk vision, which is also a democratic one — even if you set the whole action in something like a boxing ring.

It’s a pity no one ever filmed After the Fall , which has the tremendous hook of the Miller-Monroe marriage and the tragedy that ensued.

But all of Miller is worth attending to even though his most important work is in the period from the mid-40s to the mid-60s.

Miller believed — and it’s hard to deny — that he deserved a better theatre. We should be grateful, though, for the masterpieces he wrote for the one he had.

The great Willy Lomans will continue as long as there is an America of the mind with its own dream and its own nightmare. As long as there is a man who wants desperately not just to be “liked” but to be “well-liked”. And to this man, one of the most staggering figures in the history of drama as we know it, “attention must be paid”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout