Archie Moore’s tree of life and death branches out over Venice

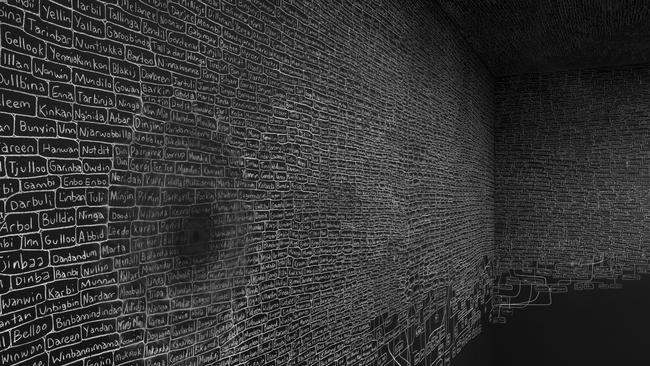

Archie Moore’s colossal, chalk-drawn family tree covering 2400 generations occupies the entire membrane of the Australian Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale.

The chalked boxes on the blackboard are disarming in their familiarity. The chaotic mathematical rubric of an unlikely genius in a Hollywood movie perhaps? Or, more intimate still, the overzealous hand of a high school teacher we all remember. Each box is etched with a name, all interconnected with lines delineated by the imperfect human hand. “Dirra. Kayi. Gwunna. Tarrum.” A colossal family tree interlaced across the entire membrane of the Australian Pavilion in Venice.

As time progresses along the tree, however, the rhythmic form begins to buckle. Names fall away to be replaced by dehumanised descriptors and the brutally opprobrious. “Blackfella. Full Blood. Bung Eye. Half Caste. Old Gin. Abo.”

“It’s a big relational map of connection,” the work’s creator Archie Moore explains of his elaborate familial chart. “Between life and death, people and places, circular and linear time, everywhere and everywhen. It’s intended to be a space for reflection and remembrance – remembrance of all of these lives represented on the tree. And everyone else that’s also connected to that tree who has come and gone … and those that are still here.”

Like much of Moore’s work, kith and kin mines the tenebrous threshold between presence and absence, and the errancy of memory. While his patrilineal line – woven of British and Scottish pedigree – presents a largely cohesive narrative, the matrilineal trajectory is pockmarked with obloquy, blanks and dead ends: a silent memorial to colonisation, racism, massacre and the wanton erasure of culture, records and language.

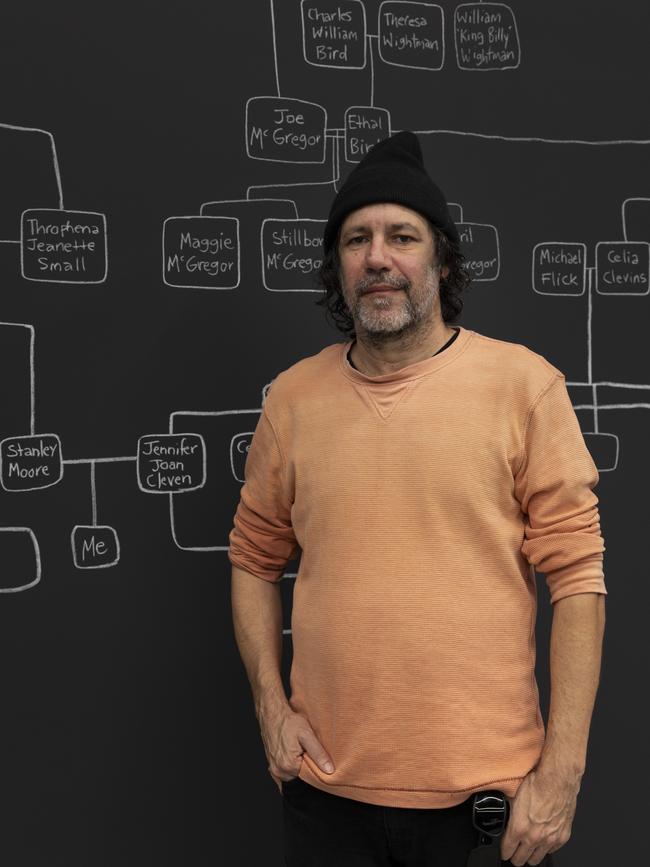

As the lines descend towards the present they suddenly converge at Stanley Moore and Jennifer Cleven, Moore’s parents. The box beneath states matter-of-factly: “Me.”

Moore was born in 1970, the son of empire and both Kamilaroi and Bigambul lineage. His was a life sculpted at the margins, impoverished and alienated between seemingly irreconcilable and binary worlds on the fringes of small-town Tara in Queensland, in the Western Downs.

Moore recalls his youth unemotionally: the leaking rooves and summer cockroach infestation. The Dettol baths and ineffaceable flu. The racist taunts and enduring loneliness. This ramshackle family home has been the subject of a number of his exhibitions, most recently in 2022 with Dwelling (Victorian Issue) at Gertrude Contemporary in Melbourne. “Other children would shame me out with statements like ‘pooooohhh! Your house is shit’,” Moore reflected at the time. “I rarely left the house. I preferred being inside its ugliness to the ugliness of racism outside its walls.”

“I was a very insular kid,” Moore adds today. “I’d stay at home, I never used to socialise. I was introspective, just trying to express myself through whatever I was drawing.”

These drawings would compel him towards Queensland University of Technology, where he earned a Bachelor of visual arts and a scholarship to study in Prague. By now the young artist’s practice was becoming increasingly conceptual, predominantly drawing on corporeal references from his childhood – corrugated iron, utilitarian school chairs and faux leather couches graffitied with the crass language and iconography of a 1970s Queensland teenager.

Kith and Kin – an evolution of Moore’s 2021 work, Family Tree – continues this reflexive tradition: what he denotes as a holographic map, representing the interconnectedness of 65,000 years of human civilisation. Moore was reared with little explicit sense of inheritance or familial connection beyond his maternal grandmother, who lived nearby in a corrugated iron hut with open dirt floors. He grew to mistrust the silence. “If someone’s not talking about something you of course wonder why,” he deadpans.

He turned to trawling DNA sites, electoral rolls, libraries, cadastral maps and social media in an attempt to fill in the empty crevices of his contemporary family story, unearthing details of a fabled great grandmother, known as Queen Susan of Welltown – whose recorded interviews with anthropologist Norman Tindale remain – as well as his father’s little-known membership of the Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffalos. Behind the seeming banality of each moniker chalked in Conté crayon would emerge a deeply consequential motif: a nameless child, an uncle under surveillance and grandparents seeking to gain permission from the Chief Protector of Aboriginals to marry.

While Moore’s inquiries often proved futile – requiring some speculative imagination to chalk in the yawning blanks – other revelations would prove as inconceivable as merciless: namely the discovery that the acreage awarded to his father’s convict European ancestors in a ballot was in fact stolen from his mother’s family and traditional owners. Moore would make an emotional return to the property – a land achingly cleaved between his own two worlds.

The family tree – canvassing 60 metres of wall and reaching five metres in height – bleeds onto the roof of the Australian pavilion, forcing the viewer to look skyward: a repository of memory for the departed, where it is believed the souls of Moore’s First Nations ancestors reside as stars.

And in the nebulous void between the starlight resides the invisibility of those who have been forgotten – an eclipse of blindness, where lives have been extinguished without trace, as though they never were.

At the very kernel of the exhibition, floating above a body of water, is a three-dimensional structure that resembles a prosaic town planning model for suburban Australia. On closer inspection these achromatic towers are hardly innocuous: 500 stacked reports on the Aboriginal deaths in custody that have occurred in Australia since the Royal Commission report into custodial deaths was first tabled in 1991. A methodical stack of paper and ink, each now a momentary cenotaph in memorial to a life erased.

“I think one of the strengths of Archie’s practice is the way he is able to speak about his personal experience and the experience of his family as a way to extrapolate and connect with other stories that are quite universal,” the Australian Pavilion 2024 curator Ellie Buttrose says. The Aboriginal deaths in custody installation is an extrapolated iteration of Moore’s work Embodied Knowledge, curated by Buttrose at Queensland Art Gallery in 2022.

“I think, yes, this speaks to Australian history but it also speaks to what is happening all around the world,” Buttrose furthers. “The universality of family and what it means to face racism – but to also show that Indigenous kinship is strong and First Nations connections are strong – comes through. It may be sombre and there is quite an emphasis on looking back to history, but there is also a sense of hope in the strength of the family. Art is not divorced from life.”

To punctuate this sentiment Moore insisted that a window be installed in the otherwise cloistered pavilion, rupturing the darkness with shards of light that connect the pool of water with the Venetian canal outside, flowing forth into the lagoon, Adriatic and onwards towards Australia. “Australia and Venice are connected,” he affirms. “Everything is connected – all people and things.” Curated by Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa, this year’s thematic maxim for the Biennale is Stranieri Ovunque: Foreigners Everywhere.

While Australia was first represented at Venice’s International Art Exhibition in 1954 by the weighty triumvirate of Russell Drysdale, William Dobell and Sidney Nolan, the nation would not secure an exclusive pavilion in the fabled Giardini della Biennale until its bicentenary in 1988 – a temporary structure later supplanted by a more permanent one in 2015.

Australia’s participation has not been without controversy: in 2017 several long-time financial donors, including high profile philanthropist Simon Mordant, withdrew support following the decision to restructure the selection process – bringing it under direct curatorial control of the Australia Council, now Creative Australia.

In the same year Australian artist John Kelly was nominated for Walkley award for his investigation into the suggested dominance of two of Australia’s leading commercial galleries – Anna Schwartz and Roslyn Oxley9 galleries – over the selection process. Kelly would bookend: “ … waiting until 2017 to give the first Indigenous artist, Tracey Moffatt, a solo exhibition in the Australian Pavilion in Venice hints at a touch of discrimination in the past. That no male Indigenous artist has ever had a solo show in the Pavilion reinforces this discrimination.”

In 2019 artist and provocateur Richard Bell would stage a spectacular protest against this explicit lack of First Nations representation in Venice and the scourge of “white art in black boxes” – reconstructing the Australian Pavilion on a barge and shackled in chains, and motoring it up and down the Rio del Giardini canal.

Moore will be the first male Aboriginal artist to present for Australia at Venice – the exhibition’s 60th iteration – and only the second solo First Nations artist in the history of Australia’s involvement. While joining an alumni that includes some of the nation’s significant practitioners – among them Bill Henson, Patricia Piccinini, Fiona Margret Hall and Moffatt – Kith and Kin is an unsettling examination of the innate contradictions at the genesis of contemporary Australian culture: a conflicted sense of identity that is coded into Moore’s own DNA, one he says remains frustratingly irreconciled.

“I still feel this otherness and this binary opposition – you can’t have one without the other,” he concludes, going on to reference his United Neytions commission at Sydney’s T1 airport terminal: a mosaic of prismatic flags that explore belonging and the uncritical allegiance to a manufactured sense of nationhood. “I myself am in the family tree, in the work, and I am trying to say, ‘it doesn’t matter about these differences, we have something much bigger in common in that we are all human beings all on this earth trying to live our lives and survive’.

“They are personal histories but they are also national histories. My story is not unique – or my family’s story. A lot of marginalised people will relate to that. Despite all of that we’ve survived and the tree continues on.”

Moving backwards in time away from the ruptures and trauma that consume the 250 years of Moore’s family tree, the frayed threads begin to coalesce into a more cohesive structural form. As memories give way to tens of thousands of years, time begins to shed its literal and linear meaning – each life weighted evenly with those that come before and after, and all wending back towards a common birthright and inheritance.

“The tree written on the walls goes back over 2400 generations,” Moore explains. “If we go back far enough, we all have a common ancestor. So it’s about every one of us and every single living thing on the planet being connected in a much larger kinship system. We are all humans, we are all family, we are all kin. That’s an indigenous way of thinking: everything is a connection to place. Indigenous people having a non-linear sense of time, more of a circular understanding of the past, the present and the future being on the same temporal plain. What is happening now has happened before.”

Moore’s voice trails off, and his memory returns to the little boy in the dilapidated shack in Tara. “You know, my father once saw me drawing and he said: ‘you’ll be famous one day’,” he reflects with a wry laugh. “I don’t know what else I could do. I’m not good at anything else. I’ve had short stints in other jobs and never lasted. This is my job. People disappear. Are still disappearing. We’re racing against time to get these stories down so they are not taken to the grave.”

The 60th International Art Exhibition opens today and runs until November 24.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout