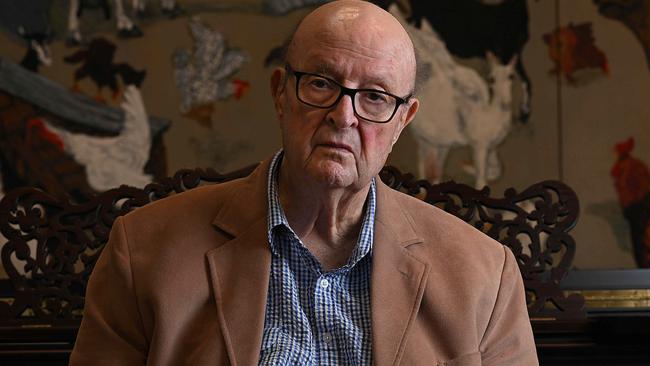

Archibald Prize-winning painter William Robinson on his grief, faith, identity politics in art and why he was an ‘absurd’ farmer

On the eve of two new exhibitions, arguably Australia’s greatest living painter William Robinson opens up about the loss of his wife and children, faith, identity politics in art and why he was an ‘absurdity’ as a goat farmer.

For 12 months after his wife, Shirley, died in 2022, William Robinson felt as if “I was somewhere else’’. The eminent Brisbane painter was so unmoored, so overcome with grief, “I wouldn’t have been able to tell you what day of the week it was’’.

He and Shirley had been married for 64 years and raised six children (tragically, in the space of 18 months, they lost two adult daughters). As his wife’s death tore a gaping hole in his life, Robinson, an accomplished pianist, found solace in music. “One thing I did do that was holding me together was playing the piano,’’ the 87-year-old tells Review in a clear and mellow voice. “There are about half a dozen pieces that I knew I could still play, and I was playing them for Shirley.’’

At one end of Robinson’s spacious sitting room is a grand, mahogany-coloured Steinway; most days, his long, confident fingers fly skilfully over the keys as he reaches out to his beloved Shirley through classical music, which he considers a spiritual art form, “filling the ether”. A painter of landscapes often described as projecting a sense of the sublime, he also found comfort in his Catholic faith and reflects: “It’s a mistake to say they (deceased loved ones) have gone, because they haven’t. And if you want to have contact with them, you can sing to them if you like, you can speak to them or you can play the piano.

“ … I suppose I sound mad but I speak to her (Shirley) every day; she’s here with me. I don’t expect other people to understand that, because I know some people would find it impossible. But we’d been married for 64 years and now it’s almost as though she’s set me off on a journey to finish things that I haven’t done.’’

Robinson is a two-time Archibald Prize winner and has garnered the Wynne Prize twice – a rare feat in the history of Australian art. His works are held in our flagship galleries, the Metropolitan Museum, Vatican Museums and the British Museum, and respected art critic John McDonald has said he could “take his place with Sidney Nolan, Fred Williams and John Olsen as one of the few completely original landscape artists in Australia’’.

Vanessa Van Ooyen, director of Queensland University of Technology’s galleries and museums, agrees Robinson is “one of the most original artists of his generation, altering the way we perceive the Australian landscape through his unique perspective. We cannot visit our country’s vertiginous hinterland or lush rainforests and not imagine one of Robinson’s artworks.’’

Van Ooyen, who also runs QUT’s William Robinson Gallery, which is dedicated to the painter’s work, tells Review: “His paintings knit this bird’s eye view together with this revolving view of the world. He was trying to turn the picture plane on itself and present a new way of looking at the world.’’

The former university art teacher is best-known for his epic, light-dappled landscapes, but now, three new exhibitions will highlight lesser-known aspects of his oeuvre, which also includes tranquil domestic interiors inspired by Pierre Bonnard, whimsical farmyard paintings, eccentric self-portraits and early seascapes.

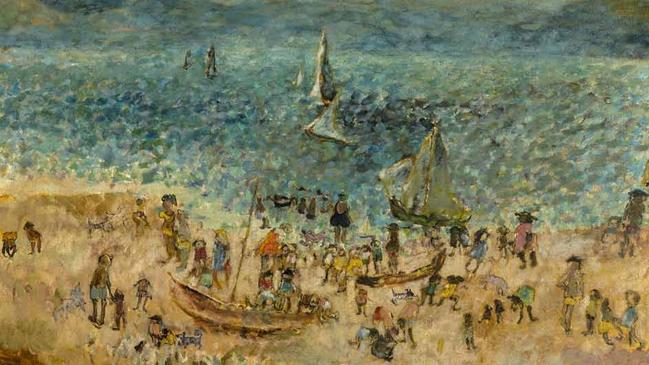

On August 15, a commercial show featuring up to 50 of Robinson’s 1970s Moreton Bay landscapes opens at Brisbane’s Philip Bacon Galleries – and remarkably, most have never been exhibited before. In September, an exhibition exploring Robinson’s printmaking will open at QUT’s William Robinson Gallery – it’s the only public gallery dedicated exclusively to a living Australian painter and it’s housed in Old Government House, a grand sandstone mansion that sits within the university’s lush grounds. Completing the trifecta, next year an exhibition of the veteran artist’s cow paintings and works on paper will be mounted at Australian Galleries in Sydney.

Robinson credits Shirley’s organisational skills with making his five-decade art career possible. He jokes that, from beyond the grave, she has set him on a mission with his daughter, Kate, sorting through paintings she kept in her meticulous archive.

“In the early days Shirley would have been picking up my drawings off the floor but now, she’s cracking the whip a bit,’’ he says with a wry chuckle.

As he grapples with his devastating loss, Robinson has clearly retained his mischievous sense of humour. Tall and erect despite his walking frame, he also shows considerable stamina as he takes Review on a 45-minute tour of the paintings in his home studio and living room, from large portraits of wide-eyed cattle to a bush landscape extending magisterially across three panels.

Since Shirley passed away he hasn’t been painting much. As we tour his studio he says arthritis means he has to hold one hand with the other, to steady it when drawing. “I’m fairly shaky,’’ he admits. Arthritis and “just all the other things you get when you get a bit ancient … I’m trying to draw as well as I can.’’

One farmyard painting in his home studio, Artificial Insemination with Pink Glove, 1984, features a huge, vaguely threatening rubber glove. “I’m standing behind my wife watching,’’ he says, playing up his persona as the permanently distracted farmer, while his capable spouse gets things done.

The Robinsons ran an off-grid goat farm at Beechmont in the Gold Coast hinterland in the 1980s. Asked about his farming skills, the artist confirms he could milk cows but adds: “Mostly, I just moved around in space … I have no idea why we left the suburbs.’’ He says the notion of Robinson the farmer was “a real absurdity’’, yet this rural property and the surrounding bush and rainforest shaped his art in a profound way. Today, he lives in Bardon, a leafy inner Brisbane suburb, where Shirley planted a garden that’s a mini-rainforest in its own right. When Review arrives, Robinson is dressed smartly in a blue blazer and quips: “I have these special teeth that I had put in because you’re coming …. As soon as you go, out they come. But if I’m going to Woolies, I’m invisible.’’

“You like being invisible,’’ interjects Kate, a former teacher who works full-time on the archive and playfully describes herself as “the fourth favourite” child.

Shirley, it seems, held back a trove of works for the official family archive, carefully preserving them in drawers at Robinson’s home studios for decades. In the Moreton Bay show catalogue, Robinson says these works were set aside “for safekeeping to preserve these moments in time’’.

Art dealer Philip Bacon, who represents household-name painters including Cressida Campbell, Robinson and the late Margaret Olley and John Olsen, says it’s “very rare’’ for artists “to hold such an archive back’’ – in his experience of local painters, only Fred Williams did this.

Even Van Ooyen is seeing some of the Moreton Bay landscapes for the first time as she visits Bacon Galleries with Review. Says Bacon: “Bill is a long-distance runner and this exhibition takes us back to the starting blocks. It’s very exciting.’’ He predicts the show will challenge people’s perceptions “of what they think they know about Bill Robinson … These earlier works are of enormous quality and very consistent. They are different in palette and more representational (than later works).’’

Robinson, whose most sought-after works can fetch $750,000, has never followed the fads of the art world, finding much of this absurd. Rather, says Bacon, “he’s very much about place. He paints what he sees from where he lives’’.

The Moreton Bay collection of pastels and oil paintings depict wispy sail boats dwarfed by a vast, open sea and small, red-roofed houses perched on a sparsely populated (now densely-inhabited) coastal ridge. There are ordinary, almost cartoonish beachgoers absorbed in everyday pleasures – sailing, swimming, paddling – many with small children in tow. Robinson also captured a jetty that stretches almost to the horizon, and an ominous black sky that bears same sense of movement as his later works.

The QUT exhibition is called The Painter and the Printmaker, and according to van Ooyen, it “pairs paintings and prints together to demonstrate that printmaking is an essential medium in Robinson’s practice”. Opening on September 5, this exhibition ranges from an early engraving of a chicken through to lithographs of daily Parisian life that Robinson made after five visits to the city’s Atelier Bordas workshop, established by master printmaker Franck Bordas. Interestingly, he and Shirley did not visit Europe until they were in their 50s, because of the demands of raising a large family and running a farm. “Would you please look after my six cows, four dogs and 20 goats? It’s very hard to find people that’ll do that for you,’’ the artist jokes.

Bordas’s grandfather worked with Picasso and Cezanne, and he once told Van Ooyen he had rarely seen a painter so skilled at lithography as Robinson was. Robinson’s prints are held at the British Museum, but Van Ooyen says that, like those early Moreton Bay landscapes, they are not as well-known as his self-portraits or rainforest landscapes.

Given his four Archibald and Wynne Prizes, a large, permanent gallery set up in his name and his three honorary doctorates, you might assume that retrospectives of Robinson’s work have been held in state galleries around the country – yet you would be wrong. In 2001, a retrospective called Darkness and Light – The Art of William Robinson, opened at the Queensland Art Gallery and toured to the National Gallery of Australia the following year.

In 2021, former governor-general Dame Quentin Bryce guest curated the show, Lyrical Landscapes, for the Gold Coast’s HOTA Gallery. This exhibition saw Robinson’s master work, the Creation Series – seven paintings that draw on the Biblical creation story and were completed over 16 years – presented in its entirety for the first time. Last year, Bryce launched a QUT exhibition, Love in Life and Art, that is dedicated to Shirley and concludes this week.

Yet as Bacon points out, neither the Art Gallery of NSW nor the National Gallery of Victoria has mounted a Robinson retrospective. “We (Queenslanders) always think that Queensland doesn’t get a fair go,’’ Bacon says with a knowing grin. “All art is parochial. I think Bill has transcended that to an extent but only to an extent. Bill has had such a big career, he didn’t need the tick (from the southern capitals).’’

Van Ooyen says NSW “absolutely” has a superiority complex about Queensland and its artists and that Robinson “is not as well known as he should be’’ in Melbourne. “Bill didn’t play the art game,’’ she says. “For anyone who doesn’t do that networking and self-promotion, in some respects, you don’t get those opportunities. For years, Bill was busy teaching. I see it with so many artists.’’

In 1998, The Australian’s then-art critic Giles Auty described Robinson’s Creation Landscape – the Ancient Trees as a masterpiece and “among the most remarkable landscapes – and visions – ever produced in the history of Australian painting’’. Auty’s praise saw luminaries from former NSW Art Gallery boss Edmund Capon to Gough Whitlam rib the artist about his “masterpiece”, but over time, the critic would be vindicated.

Nonetheless, Robinson insists: “I was never a visionary. You can’t keep goats and be a visionary at the same time.’’ Because he needed to support a large family (“a handful in anybody’s language’’) he continued teaching art and did not start painting full-time until 1989-90, when he was 54. “That brings a great number of complexities. You can’t just go to the cash register and the drawer comes out and you help yourself,’’ he says.

In a cruel turn of events, in 1991 and 1992 the Robinsons’ eldest and youngest daughters died: the couple’s eldest daughter, Jane, had been suffering from non-Hodgkins lymphoma and mental illness, and their youngest, Sophie, was killed in a car accident.

“Life brings you certain things,’’ the artist says with poignant understatement. “In 1991 and 1992 we lost two daughters – one was 21 and the other was about 32, so they weren’t children. But every parent has to cope with the things that life presents you with.’’ He says the girls’ deaths “did have an influence upon my art. The first lot of pictures I was doing were the mountains series which were to do with distance and eternity, and then the Creation landscapes with darkness and light.’’

Asked if these devastating losses shook his Catholic faith, he replies: “The only thing I had left was faith. … It must be hard for people who don’t believe in anything. I’m a wimp and Shirley was very strong and helped me.’’

“You helped each other, really,’’ Kate says gently, and he nods.

Robinson came to national prominence when he won his first Archibald Prize in 1987 with Equestrian Self-Portrait, a parodic portrait of himself on a horse – but the humour was lost on many. Even Capon sniffily described the trees in this work as “bonsai vegetables”. Commentators missed the fact Robinson was referencing Goya’s portrait of Charles IV on horseback. “It’s a marvellous picture because he’s made Charles look like a supreme idiot – extremely low IQ. The horse is huge and Charles is just sort of plonked there and he was king of Spain,’’ he says.

“ … Anything less like a conqueror you couldn’t have found than me. I thought, ‘I’ll see how far I can take this.’ It still looked like me but I had no bridle, no saddle, and I was pretending to ride it. … I went down there (to Sydney for the awards ceremony) and I was lampooned in the paper about being a goat farmer. You know, who’s this dill from the bush taking out the Archibald? I thought the Archibald was a pretty silly competition anyway.

“ … I still seemed to remain anonymous. I didn’t have woolly hair like some artists or a beard. I just looked like a fat, ordinary person.’’ He won again in 1995 for another comic painting, Self-Portrait with Stunned Mullet, in which he holds two fish and stands in the shallows in wet weather gear. “I won again where I tried to paint myself looking like the shrimp girl — The Hogarth painting of the shrimp girl is a portrait that I really admire,’’ he explains. “It didn’t cause as much fun as the first one with the horse.’’

It’s been reported that he considered becoming a concert pianist before he settled on painting and teaching, but today he flatly denies this, describing his experience in a 1950s ABC music competition as “as a chamber of horrors’’. “I can play for a few people – sort of,’’ he says, but while performing with an orchestra, he apparently lost his nerve. “If I can play well enough not to be disgusted at the way I am playing I do get something from it,’’ he says. Yet to this reporter’s untrained ear, his playing is so fluent and assured, he could pass for a professional.

He was good friends with Margaret Olley, former NGA head Betty Churcher and is admired by David Malouf, but these days he finds “I’ve really only got two people I can gossip to. I watch the development of art on television and I can’t believe that we’re following the local interests of sexuality, and transgender and homosexuality. I don’t mind what anybody is – they can be multi-coloured as well as multi-sexual. But I don’t want to listen to it all the time and have art based on it’’. It’s not a good time to be young, he reckons, “because you’re too concerned with your eyelashes and all that stuff’’.

“I hope I haven’t insulted too many people,’’ Robinson adds as he settles himself at his keyboard to record a video to go with this story. “Probably about 10,’’ deadpans Kate, who seems quietly alarmed by some of her dad’s assertions and gags, but also shares his propensity for kidding around.

William Robinson: Moreton Bay opens at Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane, on August 15. The Painter and the Printmaker opens at the William Robinson Gallery, QUT, on September 5. Philip Bacon Galleries contributed to Rosemary Neill’s travel costs.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout