Andrew McCarthy is the 80s brat who has unpacked his baggage

In a candid account of his career, 80s ‘Brat Packer’ Andrew McCarthy reveals dislocating episodes with Dustin Hoffman, Liza Minnelli and Sammy Davis Jnr before a spiral into addiction.

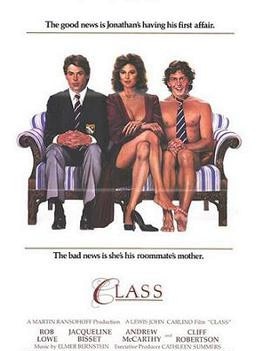

Andrew McCarthy was just 20 years old when he was paid US$15,000 for his first onscreen role, as 38-year-old Jacqueline Bisset’s adolescent lover in Class.

Bisset later invited him to stay in her Hollywood bungalow, which she shared with her lover, the alcoholic ballet dancer Alexander Godunov (“an Adonis with shoulder-length blond hair”). Chancing upon him gazing at her photograph, she “got on her knees, bent down,” and “deeply” kissed him.

The narcissism implicit in this tableau – Bisset, so stirred by McCarthy’s admiration of her image that she is sexually aroused - is at once funny and disturbing.

In his new biography, Brat: An 80s Story, McCarthy recalls similarly dislocating episodes with Dustin Hoffman, Liza Minnelli and Sammy Davis Jnr.

Director John Hughes, who made stars of McCarthy and his peers in the era-defining Sixteen Candles (1984), The Breakfast Club (1985), Weird Science (1985), and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986), is remembered by him “in a pink sport coat with padded shoulders, a large music clef pin on his wide lapel. His mullet was blow-dried into a flip just above the shoulders.”

On another occasion, McCarthy, passing an open dressing room door, saw Rob Lowe inside, chewing on a sandwich as he gazed at his reflection. “Admiring yourself, Bob?” he asked, whereupon director Joel Schumacher, walking past, said, “Wouldn’t you?”

Determined to disengage with the self-absorption demanded by the industry, McCarthy began to focus on the technology of acting – the cameras, the lights – and techniques for managing an accelerating anxiety. It was suggested that he masturbate before performing “to take the edge off”, but generally, he preferred to drink. At the premiere of Pretty in Pink (1986), his first major hit, McCarthy walked out onto Hollywood Boulevard, “looking for a place to hide.” Finding a low-grade bar, he began downing straight vodka.

Expecting nothing, he was shocked when “things that happen to famous people began to happen to me. Strangers gave me things I didn’t need, others wanted to have sex with me, and other (more) famous people began to reach out to me.” Resentments intensified. An old schoolfriend of McCarthy’s, invited back to his apartment, spat on his floor, taunting him with the words: “What are you going to do about it?” Alcohol became the dominant force in McCarthy’s life. He began dating a stripper. Success, he remembers, landed “hard upon me.”

Increasingly, he felt as if he “existed behind a layer of opaque Plexiglas” that only alcohol could clear.

His father began to call on him with growing frequency, “pressing hard” for money. As ever, McCarthy “acquiesced”, but he began to feel “undercut and destabilised by these requests.” In time, the two almost never spoke about anything else. When McCarthy mustered the courage to refuse, his father threatened to leap from a roof. McCarthy told him to jump.

When, years later, McCarthy visited his father on his deathbed, his father lunged at his throat. Could his father even see him anymore? McCarthy wondered. Had he ever? In the end, the two failed to resolve the past “but simply put its burden down.”

Eventually, McCarthy admitted himself into a hospital, where, “(p)umped full of Librium,” he “shuffled through the linoleum-tiled hallways with (his) ass hanging out of a paper robe”, struggling to overcome his alcoholism and an addiction to anti-anxiety medication. Sobriety took decades to accept, but he found peace in directing – Orange is the New Black, Grace and Frankie - fatherhood, marriage, and writing.

Famous actors can be curiously insubstantial in reality, as if, like parasites in search of a host, they only really function within the context of a character. In his rapid withdrawal from celebrity, McCarthy - who, like Rob Lowe, Demi Moore, Molly Ringwald, James Spader and others, continues to be aligned with the American Gen X group of actors known as the Brat Pack - avoided that last, lethal fizz.

McCarthy’s ambivalence about the industry was likely the byproduct of his parents’ opposing responses to his desire to pursue acting. It also precluded any real enjoyment of his success. Intimidated throughout his childhood by the rages of his domineering father, McCarthy never showed any particular talent for happiness.

“I was comfortable to stand on my own, existing in my own internal micro-stratum, engaged but separate,” he explains – and nor was he especially driven, performing drunk and stoned on occasion to combat nerves.

Intimate, melancholy and sardonic, Brat: An 80s Story reads like a Fitzgerald novella, and with the same reactive touch points: entrancement, disillusionment, removal. McCarthy, who has evolved into a man of substance, is careful never to tell the really dark stories, but their shadows fall through his words. As he writes, “even rock ’n’ roll heaven can grow wearisome.”

Brat: An 80s Story

Simon & Schuster

PP240, RRP$29.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout