Anaesthesia: The Gift of Oblivion; Admissions: Life in Brain Surgery

We know (more or less) that anaesthesia works, but we don’t really know how or even exactly why it does.

It’s a question that has plagued philosophers for centuries: what exactly is consciousness?

Anaesthetists — the people whose job it is to take consciousness away from us — tend not to worry about it so much.

You might think that’s because they’re practical people, focused on the job at hand rather than more abstruse philosophical questions. But it may be because they actually have no idea how to answer the question.

The astonishing thing is that, while we know (more or less) that anaesthesia works, we don’t really know how or even exactly what it does.

Inspired partly by her own fear of surrendering to the moonless night of anaesthesia, Melbourne journalist Kate Cole-Adams has spent more than a decade investigating the practice she calls “the most brilliant and baffling gift of modern medicine”. The resulting book, Anaesthesia, is not just an account of medical research but a poetic exploration of the mysteries of the human mind.

Every day, anaesthetists put hundreds of thousands of people into chemical comas, Cole-Adams writes, allowing “the body’s defences to be breached in ways previously unimaginable except during warfare or other catastrophe”.

Through the use of powerful poisons, [anaesthesia] has enabled entry into the secret cavities of the chest and the belly and the brain. It has freed surgeons to saw like carpenters through the bony fortress of the ribs. It has made it possible for a doctor to hold in her hand a steadily beating heart.

It is, as Cole-Adams says, mind-blowing. And yet, just how our minds get blown away, and then brought back again, remains a mystery even to those who perform this manoeuvre on a daily basis.

Although she is at pains to assert that modern anaesthesia is remarkably safe, Cole-Adams does not appear particularly reassured by the response of some anaesthetists to her questions about how the whole thing actually works: you don’t need to understand how an engine works to drive a car.

Modern general anaesthesia relies on a cocktail of mind-altering drugs, which act in different, not always predictable, ways on different parts of the brain. The three main elements of the cocktail are generally: hypnotics to create and maintain unconsciousness; analgesics to control pain; and a muscle relaxant to stop the patient moving on the operating table.

“Different anaesthetists mix up different cocktails,” Cole-Adams explains. “Each has a favourite recipe. An olive or a twist. There is no standard dose.”

Hypnotics are powerful drugs and, at higher doses, lethal ones. “In blotting out consciousness, they can suppress not only the senses but also the cardiovascular system. Every time you have a general anaesthetic, you take a trip towards death and back.”

Most of us do, of course, make it safely back but, given the imprecision of the science, it’s not surprising anaesthesia doesn’t always go according to plan.

Cole-Adams speaks to people who have experienced “anaesthetic awareness”, the ordeal of being conscious during surgery but, due to the presence of a muscle relaxant in the anaesthetic cocktail, unable to signal that awareness to operating theatre staff. Patients can be left traumatised, haunted by memories of pain accompanied by utter paralysis.

Fortunately, such experiences are rare … as far as we know. Hypnotic drugs are also powerful amnesiacs, raising questions about whether anaesthetic awareness may be more common than we realise, but rarely remembered once we emerge from our induced coma.

Even if we do remain unconscious throughout the procedure, could trauma at some level remain imprinted on us, Cole-Adams wonders, and how might that affect us in the life after anaesthesia? Might we experience ongoing emotional “memories” without consciously understanding their source?

British neurosurgeon Henry Marsh is another writer who has grappled with the mystery of consciousness, and its opposite, in his case from the perspective of someone who has spent his life cutting into living human brains.

“There are one hundred billion nerve cells in our brains,” he wrote in his bestselling first memoir, Do No Harm. “Does each one have a fragment of consciousness within it? How many nerve cells do we require to be conscious or to feel pain? Or does consciousness and thought reside in the electrochemical impulses that join these billions of cells together?’’

Marsh does not know the answer to those questions, any more than do his anaesthetist colleagues. In his second memoir, Admissions: A Life in Brain Surgery, he describes the self that is writing as no more than a “transient electrochemical dance, made of myriad bits of information”.

“This sense of self, of being coherent individuals free to make choices, is little more than a title page to the great musical score of our subconscious, a score with many obscure, often dissonant voices,” he writes.

The more you learn about the brain, about our true selves, the stranger it becomes. It is almost as though we have many competing and co-operating selves within our brains, and yet somehow they all resonate together to produce a coherent individual capable of thought and action.

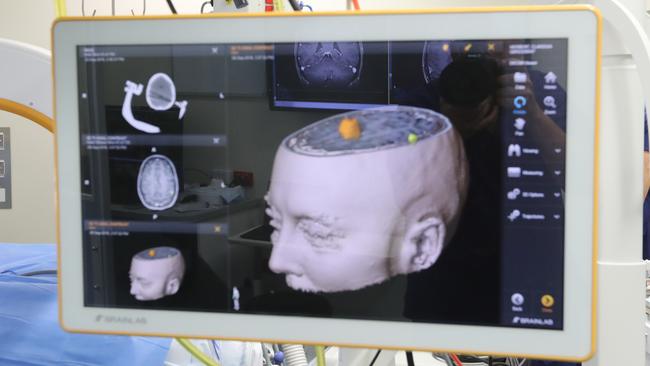

Marsh describes the surreal experience of “awake craniotomy”, brain surgery conducted without anaesthetic so that the surgeon can monitor the patient’s responses during surgery and thus avoid removing too much healthy brain tissue along with a tumour.

He often asks patients undergoing the procedure if they would like to have a look at their own brain while it is exposed.

“I have even had the left visual cortex — the part of the brain responsible for seeing things on the right-hand side — looking at itself,” he writes. “You feel there should be some psychological equivalent of acoustic feedback when this happens, but there is nothing … ”

Some of the most gripping passages in this book are those that describe the detail of surgery: the slurping of a tumour being sucked from the brain, the urgency of a sudden gush of blood that obscures the surgeon’s vision, the strange fascination of the hidden structures beneath our skulls.

After his retirement from full-time employment in Britain’s National Health Service, Marsh travels to Nepal, hoping to contribute to healthcare in the developing nation, a mission that is often frustrating given the poor prognosis many of the patients face.

There, he describes an operation to remove a large tumour from the brain of a six-year-old child and his feeling of “beauty and mystery and exploration” as he looks through the operating microscope into the child’s brain.

“As I looked down the binocular microscope, it was as though I was descending a ravine or negotiating a narrow crevice, with the shiny, silvery-grey surface of the falx to the left and the pale surface of the brain, etched with thousands of fine blood vessels, glittering in the microscopes brilliant light, to the right …

“The white corpus callosum came into view at the floor of the chasm, like a white beach between two cliffs. Running along it, like two rivers, were the anterior cerebral arteries, one on either side, bright red, pulsing gently with the heartbeat. ”

This lyrical description, however, sits alongside a brutal reality: that the child’s tumour is too large to be completely removed, that the surgery has almost certainly damaged her brain, that she will likely die no matter what the doctors do.

Try as we might, with all the tools of modern medicine at our command, the brain continues to resist our best attempts to master it.

Jane McCredie is a writer with an interest in science and medicine.

Anaesthesia: The Gift of Oblivion and the Mystery of Consciousness

By Kate Cole-Adams

Text, 405pp, $32.99

Admissions: A Life in Brain Surgery

By Henry Marsh

Hachette, 288pp, $32.99