Alexander the great: fashion without McQueen has fewer surprises

I was Alexander McQueen’s first design assistant. There was and never will be a designer quite like him. Fashion has never been the same.

March 1995, London’s East End

Nestled between a jazz club and a sex shop, down a flight of dank concrete stairs is a sparse open-plan basement. Inside are rails of garments; traditional tailoring fabrics or bath-bleached denim, slashed helter-skelter or adorned with Mongolian lamb collars. Knit dresses with sheer tulle inserts hang beside lilac taffeta, while black lace corsets with defensive spiky collars stand sentinel at the headquarters of their creator.

This is where I meet Lee Alexander McQueen. A few years his junior, I had studied at his alma mater, Central Saint Martin’s School of Art in London and our tastes clearly intersected, which is why he has invited me to meet him after he saw my final collection shown during London Fashion Week. I have been looking for a way to turn the wild creativity of fashion school into a career as a designer without compromising any of the edge. McQueen – the provocative underground designer whose Dante collection had tongues wagging – is doing just that, striding towards the precipice of notoriety and acclaim. And now McQueen, scruffy, pudgy, all post-punk cool, was striding towards me.

March 2001, Avenue George V, Paris

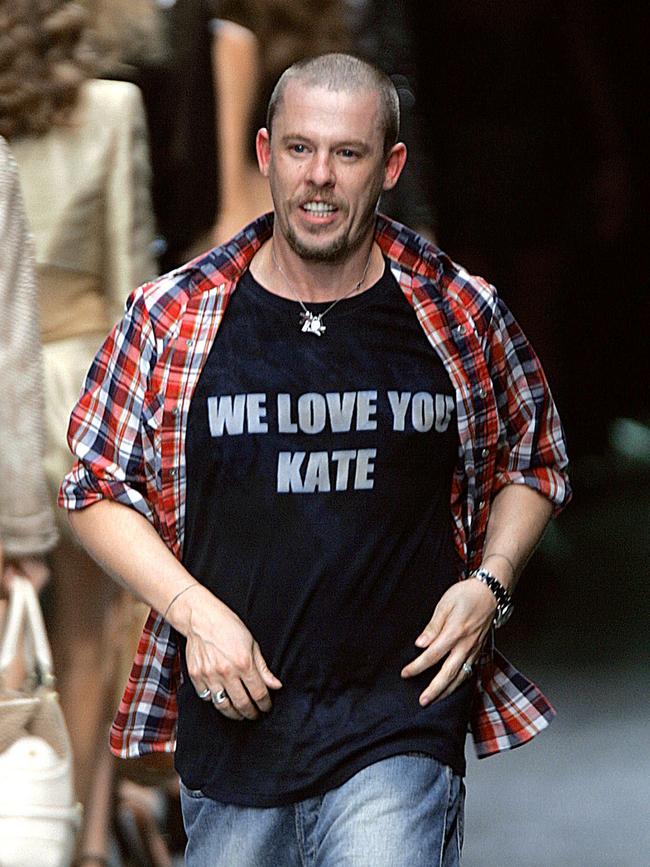

McQueen’s final show as head designer for Givenchy has been relegated to an in-house presentation from which the press had been banned. It will be remembered as one of the most beautiful couture finales never to be seen – a picture of elegance in tailoring and vision. This is the last collection I worked on with Lee. Backstage, a svelte, tanned well-groomed Lee cries and hugs the Givenchy team. We are all moved by the emotion of the show and sleepless nights that had preceded it. Lee is exhausted. But he also is excited too. Lee Alexander McQueen is leaving this fusty fashion house forever to concentrate on his own label, the latter where it all began. And it doesn’t hurt that he is multimillions of dollars richer to boot.

Between those two dates, I worked at Lee’s side on nearly 30 shows. Ten collections a year. I bore witness to a whirlwind of superhuman creativity. With each collection, Lee strove to surpass the last. McQueen went from a dreary damp underground basement in London’s grimy Hoxton Square to the perfectly proportioned luminous salons of Avenue Georges V, Paris. The man and his work had changed as radically as his surroundings, and he had taken me on that rollercoaster ride with him.

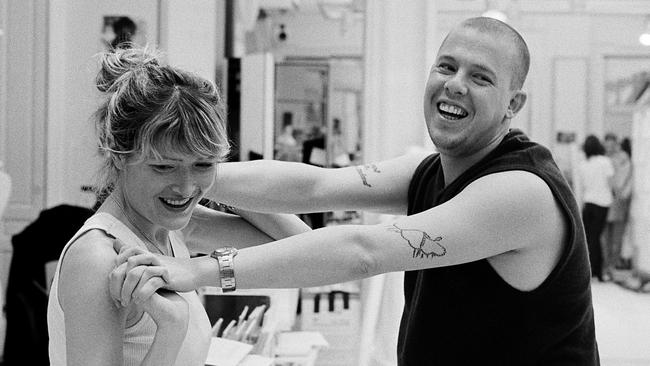

A few months after I was appointed the first designer at McQueen, Lee and I found ourselves seated alongside each other at two industrial sewing machines. We worked late into the night in an empty studio. Thanks to McQueen’s recent appointment as creative director at Givenchy, and mine as his assistant, this was a new and far superior work room. Lee’s fashion family had also become de facto employees – PR, stylist, jewellery designers, art directors and show producers, St Martin’s fashion graduates and some very wide-eyed interns. We were working on 1997’s It’s a Jungle Out There show in London. We guided our work under the needle, stitching warrior-esque jackets Lee had cut directly on the mannequin earlier that day. A film crew from the BBC had been in, and we would watch the showman at work, casually performing for the camera, jokes flying at the same speed as his scissors, with which he slashed wildly. A stapler, not pins, would hold the pieces together. Later, in companionable silence we carefully took out the staples, perfecting the silhouettes for the runway.

But the symbiosis went deeper than just thread and fabric. He had taken the raw essence of my own work and was weaving it into his own narrative. I was thrilled that the result a few days later, was an army of kick-arse Amazons stalking their way down a runway.

Givenchy rented an apartment just off La Place des Vosges in Paris, and as I transitioned to being Lee’s first designer for the couture house, the apartment became my home for 10 years. It was Lee’s Paris pad for three. The London team and various friends, passed through or camped out in the living room, tottering around in the high heels I had designed for the shows, dancing to Missy Elliot, filling ashtrays with endless cigarette butts, watching camp videos and preparing nights out in Le Marais. Work and home life were never far apart, though, and once when the deadline approached, Lee could be creatively unpredictable. Once he decided at the last minute to design an entire ready to wear collection ... on the washing machine. I think it was on spin cycle at the time. When inspiration struck, he would draw a figure freehand, slip it under the ream of paper as a guide and the designs would fly.

But there were increasingly melancholic moments in the apartment too, the late-night heartaches wondering if his boyfriends were more interested in his success than in him, the post-show depressions after the French press’ lacklustre reactions when he desperately wanted to be loved. Then there were the early mornings when his black and silent moods in the car on the way to Givenchy left us apprehensive. When I first began to learn French, I was keen to learn the phrase des humeurs changeantes as Lee’s moods began to swing quickly from fun-loving friend to metal-hard task master.

The collections came thick and fast and I found I was no longer sewing at Lee’s side. In Paris the white coat-clad army of petites mains in the attic ateliers – and no longer the brilliant London studio team – would turn Lee’s vision into 3D with minuscule hand stitches and mathematical precision.

Lee often left me challenges to test my own mettle when I returned from Paris. On the eve of the Eshu show in 2000, he handed me several metres of raw indigo denim and described a bleached and re-embroidered punk puff-sleeved crinoline ball gown. I had less than 24 hours to perform this alchemy, and when, exhausted I went home for a short nap, Lee sent his assistants to drag me out of bed to finish it.

At Givenchy I designed at Lee’s side, researching ideas, meeting with suppliers and the commercial directors, explaining designs to the ateliers and fitting and filling in the collection wherever necessary. I also designed all the shoes and bags for several years. As the workload began to drain Lee, I would be sent to London to get him out of his own bed when the thought of coming to Paris was too unbearable for him and the studio took over designing entire pre-collections.

Despite the changes, there were also constants. “Look at Kaffrin Hepburn, look at M.C. Escher” Lee would say in gruff cockney at the beginning of nearly every collection at Givenchy when he was stumped for a new theme. Thoroughly wrung out by the previous collection which would barely have been finished and often not yet shown, we were on to researching the next. Hepburn, a glamorous but headstrong film star, unconventionally sporting men’s clothes but shunning men’s advances and M.C. Escher, the Belgian graphic artist known for his “impossible drawings” and “metamorphoses”, morphing one natural object seamlessly and rhythmically into something entirely unexpected. Not such random places to begin for Lee McQueen.

While plagued with accusations of misogyny, he had seen quite enough of it growing up to be a staunch defender of women against male violence and saw a raw power in the female form. Clothes became armour. Sensuality was a weapon to attract. As a female designer, I felt safe to express fantasy and sexuality under the cloak of his vision and he took the flak for some of my own creations such as the thong-backed leather bodies in the Eye collection (Spring, summer, 2000) which had been cited as proof of his objectification.

As for the sublime tailoring, with experience Lee began to realise it wasn’t possible to create each collection from zero which previously had been his modus operandi. One season, to the surprise of the ateliers, he asked them to make up three identical and perfectly tailored suits from a previous collection. In the fitting, he rapidly slashed into them, adding folds and sweeping trains, transforming the ordinary with asymmetrical sculptural poetry into three sartorial graces. (The French Village collection Spring/Summer 1999).

Pattern and embellishment were naturally key. Finding someone to sell you feathers, embroideries or silk flowers in London was quite a challenge, but Paris had numerous fine ateliers. Lee clocked their skill and ideas and then raised their game, refusing to hear that anything was impossible and then took that expertise back to London where his own collections grew in sophistication and his imagination stepped further toward the extreme.

Givenchy was becoming more and more a thankless chore for Lee. He took to saving the best ideas for McQueen and reusing the ones we had developed in Paris to enhance his own collections. The fun late night frolics around the studio, fuelled with champagne, to a soundtrack of Michael Jackson or Erika Badu, ceased. Lee was even sent home for not being serious enough on the eve of one haute couture show. Everyone was growing up. Lee was growing bored and resentful.

Still, second best was never an option for Lee, and despite LVMH CEO Bernard Arnaud refusing the press access to the two final Givenchy shows after he trumped LVMH by selling his own brand to the then Gucci group, the collections were his most coherent for the house.

His departure from Givenchy gave him a new momentum and boost and I was thrilled to see something of the old Lee. He asked me to accompany him back to McQueen in London but by this point I had fallen in love with Paris and felt ready to go it alone. I had learnt so much from Lee, a designer who trusted his instincts, who created poetry in the cutting of clothes, and who redefined the catwalk as performance art.

On a warm spring day 10 years later I was walking past the McQueen shop on the Via Sant Andrea in Milan. The shop window was empty except for a huge vase of magnificent white lilies. Although it was several months after his death, it was here that I was suddenly overwhelmed by the tragedy and sadness of his death which I had been unable to process until then. I fought back the tears, wondering how he could have been so alone, so terribly low. My experience working with Lee was one of being part of a very close family, but his success had perhaps isolated him. When the most important member of his own family died, his mother Joyce, I wish he could have had found comfort, love and support enough to carry him though rather than taking his own extraordinarily talented life.

Fashion since Lee has fewer surprises. No one looks at the world with his curiosity; no one has pushed the boundaries with Lee’s courage, clarity of vision and skill. While my own career has continued, the highs have never been as high as when I worked with Lee during those rollercoaster years.

He strove for excellence and originality, for innovation and for insight, and through those prisms he brought out the very best in the people. He brought out the best in me. But he was also human. I miss him. The world misses him.

Lee Alexander McQueen was a complicated man. A genius. A rule breaker. The enfant terrible of international fashion. A mentor. A visionary. A friend.

McQueen opens at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, on December 11. Lifeline: 13 11 14.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout