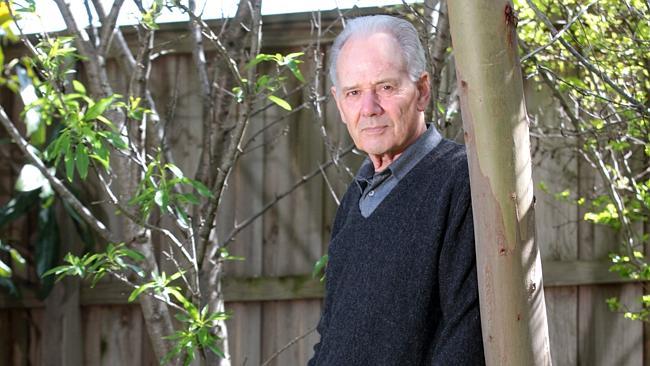

Alex Miller bids farewell to writing life in The Simplest Words

The anthology by Alex Miller, The Simplest Words, invites readers to take stock of the writer and his written works.

The Simplest Words is a novelty. It’s an anthology of a living writer’s work, a sort of Portable Alex Miller, but also a farewell to the writing life — as it’s been this far. Miller has said he has written his last novel, but he also declares in this new book that “life without writing is not only no fun for me, it is also life without meaning”.

The Simplest Words invites us to take stock at least as much of the person as of what he has written. The autobiographical and reflective pieces predominate, whereas excerpts from the novels are each only a couple of pages long.

Miller has won the Miles Franklin Literary Award twice, and his reputation rests wholly on his fiction. At least until now fiction for him has been the pre-eminent writing genre. “My interest,’’ he writes, “is in the currency of the intimate lives of ‘us’, and neither the historian nor the biographer can safely deal in such a currency. Private intimacy is of necessity a language requiring something more than textual and eyewitness sources. One has to make it up.’’

Ironically there is much in this collection that, in different ways, undercuts this claim. The longest pieces of fiction are two short stories, and perhaps because they are complete they impress far more than any of the excerpts from the novels. They are both early Miller, 1975 and 1976. The second, How to Kill Wild Horses, an account of a brumby cull, takes its power from the calm, detailed precision of the narrative. “The intimate lives of us” do not feature at all.

Recently, late in Miller’s career, he seems to have found himself in quite starstruck admiration of works that are not novels but are certainly dealing in the intimate lives of us. Of all the writers mentioned in this book, none evokes greater praise than Hazel Rowley, especially for her biography of Christina Stead. Miller describes this as “central to the richness of our literary life”, and adds that “there is a sense here that the biographer finds something central to her own life in the life of her subject and shares with her subject something of the same vulnerabilities”. Which surely must be writing about our intimate lives. And of course a biography, like a novel, is also made up because biographers and historians, as much as novelists, have to imagine and select the elements of the stories that open in front of them, and that they then follow.

Miller has been serious about his vocation. He repeatedly emphasises that “at least part of the job of the novelist [is] to bear witness to the emotional and moral questions that haunt our lives”. He makes the concession that the novel can also be entertainment, but his heart doesn’t seem to be in it. It’s noteworthy that there’s not one joke or light moment in The Simplest Words. All the heavy burden of a mucked up world weighs on him. He recalls as a primary schooler in London watching newsreels showing British troops entering Belsen and Buchenwald. “The overwhelming impression left on us young children by these nightmare images was that we (human beings) do this to each other. A sense of guilt by association was inescapable.”

I wonder whether he is justified in making this claim for all his classmates, but this book makes clear that Miller himself has been in a ceaseless wrestle with guilt. Elsewhere he quotes one of his own characters. “None of us willingly dies unclean ... Religious or not, to seek confession and absolution is surely an essential moral imperative of the human conscience, isn’t it. To absolve means to set free, and that is what we yearn for, freedom.”

Perhaps the reverse side of the horror at how human beings can treat one another is Miller’s own generosity of mind. He mentions dozens of people. Most of them seem to be friends, but all of them are thanked, commended, praised for their qualities. Behind this I even suspect that Miller feels himself, at least on the literary scene, an outsider — English migrant, farm labourer and stockman, autodidact. He’s a little too ready to mention prizes and praise he’s won and celebrities he knows. Yet undoubtedly he has responded warmly and generously whenever he’s seen a hand of friendship extended. Miller has the reputation of being a nice guy.

The Simplest Words is full of far from simple arguments, and there are many I would enjoy seeing Miller tease out in later essays. In spite of his insistence that his novels are made up, he says “all my major characters in all my novels have been based on real people. I’ve had only one objection ... he is the only one to have disliked his fictional representation.” I want to read him at greater length on what “based on” means, on what is made up, on what obligations he feels towards people who are immediately recognisable in their “fictional representation”.

On a more cosmic scale, he offers one peculiarly challenging thesis: “I believe there are profound moral and spiritual consequences for us in pursuing knowledge at all costs. One enormous impoverishment that European culture has suffered because of the unbridled passion to know is a loss of the idea of the sacred. This loss is experienced by growing numbers of people as a deepening divide between themselves and their sense of belonging.”

What’s all this about? Is Adam and Eve eating of the Tree of Knowledge behind it? Why must knowledge dispel the sacred? Couldn’t it in fact enhance it, as in “the heavens proclaim the glory of God”. The thesis is too big for this passing summary. I want Miller back again, in another essay, spelling and arguing it out.

“I don’t like writing directly about myself,” he says, but both directly and indirectly most of The Simplest Words is in fact about himself. Two of the great friendships he celebrates here are with Rowley and philosopher Raimond Gaita. When Gaita sends him an essay on his own mother, he comments that it’s “written with great courage and honesty ... with a confessional honesty far beyond anything I would be capable of”. And he writes to Gaita that “I could never write of such intimate moments in the life of my parents and myself”. Why not? There may be many good reasons, but he doesn’t delve, despite hinting several times at a dark secret, a traumatic past. If the post-fictional Miller is moving into a more essayistic or autobiographical mode, some facing of these issues seems necessary.

In addition, the personality-centred pieces in this book are more appealing than the moralising or semi-philosophical ones. The most enjoyable are those on his friendships with Gaita and Rowley. Indeed the essay on the latter presages a book that would be full of vitality and intimate human interest. For eight years, until her death in 2011, Miller and Rowley exchanged emails daily. He reproduces just two of them.

Gerard Windsor is an author and critic.

The Simplest Words: A Storyteller’s Journey

By Alex Miller

Allen & Unwin, 369pp, $35 (HB)