Against the odds, women kicked AFL goals 100 years ago

In fits and starts, women’s AFL has been hampered and helped by world wars, cultural change, and popular opinion.

In Play On!, there’s a photo of a women’s football team from a small farming community in Western Australia. Players have their arms crossed, as was standard, and are wearing baggy shorts and sleeveless guernseys. Many are wearing headbands. Unlike so many photos from the past, there are grins. They look relaxed, like they are having a tonne of fun. It’s 1927.

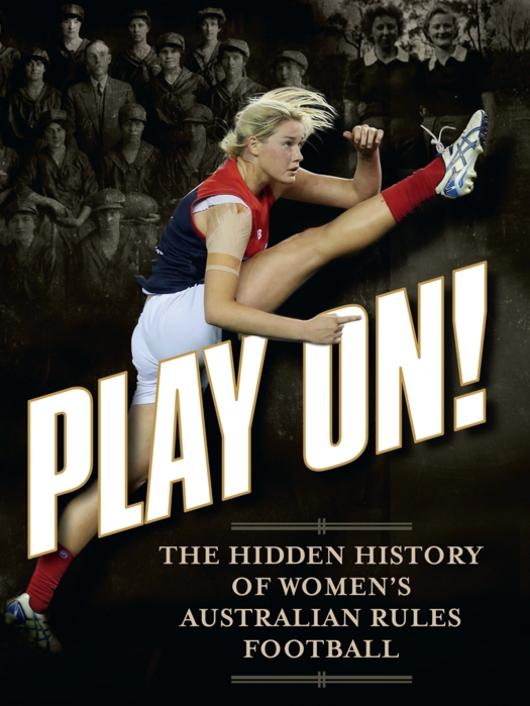

In this timely book, Brunette Lenkic and Rob Hess explore the development of women’s Australian rules football. It is a blow-by-blow account of the behind-the-scenes action led to a professional league today. In fits and starts, this was hampered and helped by world wars, cultural change and popular opinion. But, in 2017, the inaugural AFL Women’s season is in round seven this weekend.

With all of the hype surrounding the new league, it is sobering to see the date under one of the first photos: 1917. Reading Play On! it is impossible not to think that here we are, 100 years later, just getting professional women’s footy up and running. Progress has been painfully slow.

Some of the first recorded matches were played by workplace teams. In 1917, Foy and Gibson department store had a women’s team in Perth. Eye hooks kept their voluminous skirts from blowing up. Can you imagine Tayla Harris’s mighty splits-kick done in a full skirt? Shoes came off frequently, mid-kick, and some played barefoot.

There were married versus singles matches, and games involving footballers’ wives. In 1929, a record 41,000 spectators watched a women’s match at a charity carnival. Because games were often light entertainment, sometimes involving men and women in dress-ups, there was criticism: “The general public must deplore the trend to exploit, in the name of charity, silly girls who will join in these burlesque matches”, growled Melbourne’s Sporting Globe in 1947.

In 1921, the Cathedral branch of the Mothers’ Union was outraged at the immodest, boisterous behaviour, and warned that men would lose respect. In Melbourne’s Sun News-Pictorial in 1947, Jack Dyer, captain-coach of Richmond, fretted that women’s “minds would be bewildered by the rules” and that football would “harden women’s muscles, spoil the shape of their legs and probably coarsen their whole appearance”.

Plus ca change. Graham Corns opined in The Advertiser as recently as 2015: “They had the skills, the balance, the fitness, the aggression and the competitive edge that defines good sportspeople but there was something amiss. It just didn’t look right! … Perhaps it was the outfits. They wore boys’ footy jumpers and shorts. Not particularly flattering.” This neatly outlines why change has been slow.

In a time before social security, when charities were heavily relied upon, games raised money for convalescent homes, unemployed girls, women’s refuges, and wartime food parcels. In 1916, men’s sporting clubs ceased activities to encourage able-bodied men to go to war, and some Perth employers found a way to use women’s football to shame men into enlisting.

It is telling that teams had names like Collins’ Cuties and Henderson’s Honeys, after their coaches (Jack Collins, Herb Henderson). In 1934, a Brisbane Sunday Mail article worried about “the ruination of athletes’ future suitability as wives”. There was a lot of concern about physical danger, and the press was often mocking, but attitudes were gradually shifting.

In 1954, when Evelyn Mooney played in a men’s team, the Morwell Advertiser reported that women had “invaded one of the few remaining aspects of sport regarded as a man’s prerogative”.

There was no law against women playing in a men’s team, and in 1995, Sally Rees from the Darebin Falcons nominated for the men’s draft. Draft rules were immediately amended to prevent similar nominations. As late as 2003, the University of Melbourne women’s team wasn’t allowed to train on the main campus oval.

What becomes apparent is that the men’s game has a lot to learn from the women’s in terms of acceptance of LGBTI players. The game has been a safe space for women; it’s likened to being part of a big family.

In 1998, brothel Langtrees of Perth offered cash sponsorship for the right to brand the uniform of a WA team dubbed “Wicked Women”. The money had to come from somewhere, after all. Women’s football has been largely under-resourced and run entirely by volunteers. Names appear and reappear, women who have given tirelessly of their time and expertise.

Play On! is full of entertaining anecdotes but the language can be a bit fusty and the detail a bit repetitive. Sentences that don’t require a run-up begin with “it should be noted that” so the overall experience can be exhausting. Too often it reads like a history for nerds, not meant to entertain a general audience. But having said that, it also holds a great deal of gold.

The development of the women’s code came from regional towns as much as big cities. Marlene Dunn, pictured in her footy gear in 1957, played in the undefeated team for Trentham, Victoria. Jess Cameron, part of Collingwood’s AFL Women’s league 2017, is her granddaughter. She also won Australia Women’s Cricketer of the Year in 2013.

Imagine if Collingwood star Scott Pendlebury played professional cricket in the off-season. In 2017, AFL women’s players are paid for nine hours of work a week. There is a future when our sportswomen will be paid enough so that they don’t have to be all things. Bring it on.

Louise Swinn is a writer and publisher and, though she doesn’t admit it here, a Geelong tragic.

Play On! The Hidden History of Women’s Australian Rules

By Brunette Lenkic and Rob Hess

Echo, 324pp, $32.95