After the downfall: Louis C.K.’s comedy revival and his 2022 Australian tour

He once was described as the ‘Jimi Hendrix of comedy’, then the US performer met a swift comeuppance that excluded him from public life. Five years later, he’s back.

If you are familiar with the American comedian Louis C.K., whether by name or by his reputation as a once-revered stand-up comic, it is probably in the context of what happened five years ago, when he was, for all intents and purposes, cancelled.

The revelation of his behaviour was so appalling, and his comeuppance so swift and complete that, at the time, it seemed all but impossible for him to ever return to public life, let alone start performing again – but we’ll come to that later.

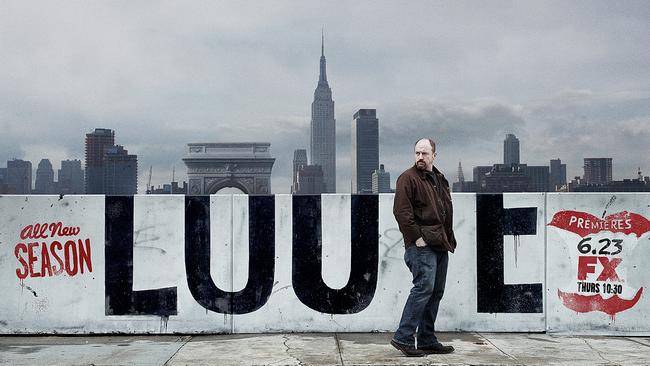

You may also know him as the creator of Louie, a television series that screened on the FX cable channel in the US – and ABC2 in Australia – across five seasons from 2010 to 2015.

Written, directed, edited and produced by C.K. – who was born Louis Szekely in 1967, but shortened his surname to its sound-alike initials – Louie was ostensibly a sitcom by definition, given that it was written to put actors in comical situations.

Interstitial scenes showed the comedian at work, standing against a brick wall and telling jokes to an audience at the Comedy Cellar. The title character – also played by C.K. – was a single father with two young daughters living in New York City, and although clearly based on his own story, the travails that Louie encountered in each episode were inflated or distorted based on the creator’s uniquely warped sense of humour.

The debut episode, for instance, began with C.K. on stage talking about volunteering during lunchtime at his four-year-old daughter’s public school, a role which often involved helping them open the fiddly spout on their cardboard milk cartons. “I’m not better at it; I just deal with the stress better than they do,” he said. “I don’t cry like a little bitch because I can’t open my milk. I’m a man.”

The narrative then cut to Louie – the character, not the comedian – accompanying his older daughter on a school trip to the Bronx Zoo led by a typically exhausted teacher. A hectic jazz soundtrack added to the tension until the situation sharply turned surreal.

After the bus got a flat tyre, the driver pulled over in Harlem and immediately returned to reading his newspaper rather than helping. After being hassled by Louie for his callous disregard, the driver got out to walk home – but not before calling the stressed dad a “red-headed nobody piece of shit”.

Stranded, Louie was struck by an idea; he called a friend, and a fleet of stretch limousines appeared out of nowhere to take the students home. The kids learned little from the trip, but now had a great story to tell.

All this took place in the first nine minutes of the TV show that C.K. created. The second half of the episode was devoted to an extraordinarily uncomfortable date, in which Louie tried in vain to connect with a younger woman played by fellow comic actor Chelsea Peretti.

Things became so awkward and tense between them that, when Louie finally leaned in to try and kiss her as they sat at a park bench, Peretti recoiled and ran away into a waiting helicopter that was parked nearby. She gave him the middle finger as it flew away, while Louie watched in despair.

From the beginning, the tone was set on two fronts. As the creator, C.K. was willing to invest the show’s relatively meagre budget by filming surprising set pieces – co-ordinating the arrival of 20 limos and their drivers; hiring the helicopter and its pilot – in order to heighten the absurdity.

And based on C.K.’s own experiences and subsequent comic observations, Louie was written as a deeply flawed protagonist. His life was imperfect, and so was he.

While constantly in battle with forces stacked against him in this twisted version of reality, he had a good heart, and generally tried to do his best for those around him, particularly in raising his two daughters, despite the challenges they constantly presented him.

Towards the end of the season finale, after a terrible night out, the character climbed on stage at a sparsely attended comedy club to make the following statement to whoever was listening.

“I’m 42; I’m really good at masturbating,” he said. “I’m, like, the best masturbator on the Planet Earth. There is nobody better at that than me, so I’m going to continue to excel at that. I’m going to focus on that, and raising my children. I know it’s not nice to say both those things in one sentence, but they happen to be the two things that I do the best.”

After jogging home from the comedy club and paying the babysitter, the season concluded on a gorgeous, tender note. Woken by his 4am arrival, Louie’s daughters asked to go out for breakfast, so the sleepless dad and his two pyjama-clad girls shared pancakes at a diner, before the camera slowly panned to show the darkness starting to lift over the NYC skyline as a new day dawned.

For many fans, the entry point to C.K.’s sharp mind was a breakthrough guest spot on US TV talk show Late Night with Conan O’Brien in 2008. There, the comedian angrily lamented that “everything’s amazing and nobody’s happy”, and used the then-novel example of in-flight wi-fi to illustrate how our interactions with society’s incredible technological leaps tend to be almost instantly neutralised by our collective impatience and entitlement.

After 15-odd years of working as a little-known comic and writer, that brilliant four-minute rant became a viral “bit” on YouTube, and the springboard that helped finally launch him into the pop culture stratosphere.

C.K. would spend nine years riding high up there, accumulating praise and accolades, while his FX series Louie became an award-winning and critically acclaimed hit across its five-season run.

He was that rare performer who could sell enough tickets to fill New York City’s Madison Square Garden eight times while also retaining complete control of his art, on stage and off, without ever resorting to hiring outside writers to help him amass jokes, or the live comedy equivalent of “playing the hits” by retelling tried-and-true material.

Among his colleagues, he became revered for the remarkable discipline of jettisoning an assembled collection of stories and bits every year or so, after filming each hour-long set, in order to stay fresh and hungry in his art.

“Louis’s effect on stand-up reminds me of what happened when Jimi Hendrix went over to London,” fellow US comic Patton Oswalt told GQ in 2011. “Everybody used to fight about who was the best guitarist, who was No.1. Then Hendrix came along, and everyone was like, ‘OK, we can all relax and talk about who’s No. 2 now’.”

C.K.’s dream ascent came crashing down in November 2017, when five women told The New York Times that his riffs about masturbation in his comedy had a disturbing connection to real life, in what amounted to serial sexual misconduct.

In a lengthy article, four women reported that C.K. in the late 1990s and early 2000s had asked if he could expose himself and masturbate in front of them (three consented; one declined the offer), another said she heard him masturbating while they spoke on the phone.

The article’s publication followed hot on the heels of The New York Times’s first investigative report about misconduct by the American film producer Harvey Weinstein, signalling the beginning of what became the #MeToo movement. “It marked an emerging agreement that Weinstein-like conduct was unequivocally wrong and should not be tolerated,” wrote one of The Times reporters, Jodi Kantor, in her 2019 book She Said.

“Cancellation” is a loaded and overused term, but in this case, there is simply no better word for what happened next. No criminal charges were laid against him, but of the aftermath following that first report, Kantor wrote in her book – co-authored with Megan Twohey – that C.K. “lost the distribution of his about-to-be-released film, the backing of his television network, and his agency, manager, and publicist. The entire process felt concentrated and accelerated: a trip from tip to downfall in less than a month.”

Although he had refused to answer questions prior to publication, C.K. responded in a statement issued the following day. “I want to address the stories told to The New York Times by five women named Abby, Rebecca, Dana, Julia who felt able to name themselves and one who did not,” his statement began. “These stories are true.

“At the time, I said to myself that what I did was O.K. because I never showed a woman my dick without asking first, which is also true,” he wrote. “But what I learned later in life, too late, is that when you have power over another person, asking them to look at your dick isn’t a question. It’s a predicament for them. The power I had over these women is that they admired me. And I wielded that power irresponsibly.

“I have been remorseful of my actions,” he wrote. “And I’ve tried to learn from them. And run from them. Now I’m aware of the extent of the impact of my actions. I learned yesterday the extent to which I left these women who admired me feeling badly about themselves and cautious around other men who would never have put them in that position.”

By allowing his selfish sexual desires to overrule the fair and reasonable treatment of women he worked with, C.K. put them in a hideously imbalanced power dynamic.

It was deeply wrong; to some, he will forever be inexcusable and unforgivable.

“There is nothing about this that I forgive myself for,” he wrote in his apology statement in 2017. “And I have to reconcile it with who I am. Which is nothing compared to the task I left them with. I wish I had reacted to their admiration of me by being a good example to them as a man and given them some guidance as a comedian, including because I admired their work. … I have spent my long and lucky career talking and saying anything I want. I will now step back and take a long time to listen.”

He did just that, disappearing into the proverbial wilderness, publicly chastened, becoming that “red-headed nobody piece of shit”.

Gradually, he returned to public life, and to the world’s comedy stages, while working out new material. That’s what a stand-up comic does.

Whether or not he would retain a fanbase was an open question, both at home and abroad. But after announcing dates in three Australian cities in August, tour promoter TEG Dainty swiftly added more to meet demand. Of his seven Australian performances to be held this month, all but two are complete sellouts, with overall ticket sales in excess of 20,000.

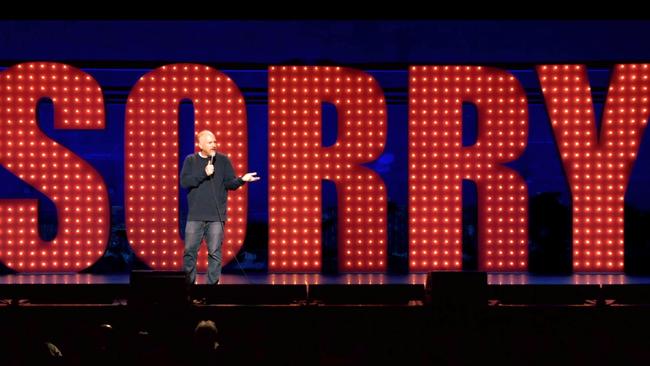

Naturally, he had to address the elephant in the room eventually.

Towards the end of his 2020 comedy special, titled Sincerely, Louis C.K. – which, like all his work now, is available to watch only on his paywalled website – he told a packed crowd, “Here’s my advice. If you ever ask somebody, ‘Can I jerk off in front of you?’, and they say yes, just say, ‘Are you sure?’ And then, if they say yes – just don’t f..king do it.”

Louis C.K.’s Australian tour begins in Perth on November 10, followed by dates in Melbourne and Sydney before ending in Brisbane (November 17). Review’s request for an interview with the comedian for this piece was declined.