AFL sensation helps kids cope with the pain of a parent in prison

Forget how tough you think you are: going to prison is scary. If that’s true for grown men, imagine how it feels for a child, having to visit their dad in there.

Forget how tough you think you are: going to prison is scary. If that’s true for grown men, imagine how it feels for a child, having to visit their dad in there.

“It’s the kind of place you just don’t want your kids to see you in,” says Andrew Krakouer, who was still in his 20s when he went to jail.

“There are dogs and guards, and I couldn’t believe I’d put my daughters in a situation where they had to go through that to see me.”

And yet he did.

But first … Krakouer.

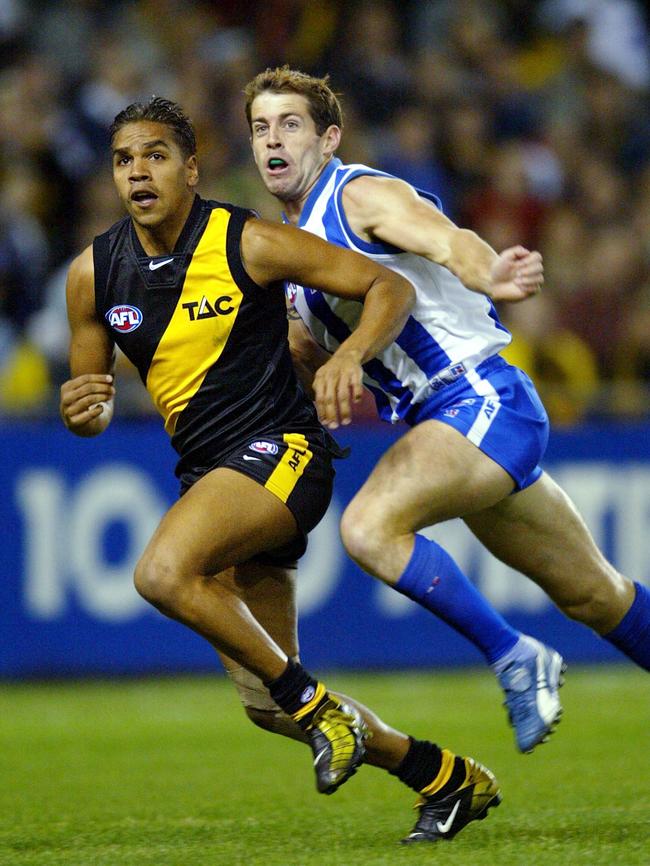

The name will be familiar to readers, who remember Andrew as the gifted AFL footballer, as swift and charismatic as any who played. And he had pedigree: Andrew is the son of Jim Krakouer and the nephew of Phil Krakouer, brothers so intuitive they seemed able to pass to each other without even looking.

The whole family was electric.

And then it all came tumbling down.

On Christmas Eve in 2006, Andrew, along with his brother Tyrone, was charged with assault causing grievous bodily harm after an incident outside a pub in Fremantle. The court heard there had been some “tribal business” involving two Indigenous families. Andrew was found guilty, and sentenced to 32 months in jail.

“I did the wrong thing, I don’t back away from that,” he says. “I take full responsibility for that.”

He has no clear memory of speaking to his two daughters, who were still in primary school, about what would happen to them and their mum, when he - the breadwinner - went to jail.

“The message was passed on to them that I did something wrong and I had to go away to prison because of it, and that is where they would have to come to see me,” he says. “And as much as I hated the environment, (their visits) were something that got me through.”

After serving his time, Andrew did what he could to put his AFL career, and then his life, back together. Dwelling on the past didn’t appeal to him. But now he’s in his 40s – the reflective years – and he’s wondering whether talking about his experience might help others. To that end, he recently agreed to address students at St Kevin’s, a private boys’ school in Melbourne.

By chance, Jacqueline Dinan was in the audience. She’s the mother of three boys and, until recently, she was a foster carer.

“I did it for five years. A number of the children would mention at bedtime (when children are at their most vulnerable) that their mum or dad were in prison, and I wanted to find a book that might help them.”

She looked around, but the books she found were mostly American. Then she heard Andrew speak, and thought: “He’s very courageous, the way he’s telling his story. And I was pondering how he could use his profile to help.”

The issue is perhaps larger than readers realise: at June 30, 2023, there were 41,929 prisoners in Australia, which means that some 75,600 dependent children have an incarcerated parent (or parents.) The problem is acute in Indigenous families: despite the fact Indigenous Australians account for just 3.8 per cent of the population, they comprise 33 per cent of prisoners (Indigenous men are jailed at 16 times the rate of non-Indigenous males, and Indigenous women are imprisoned at 23 times the rate of non-Indigenous females).

Asked if he knew a single family when he was growing up not touched by incarceration, Andrew says: “No. Not one.”

He wanted to help where he could, but says: “I’m a private person. But, then, maybe it would have helped me when I was growing up, too.”

Because besides being a father who went to jail, Andrew was once the son of a jailed father.

Andrew says he “was 10 or 11, something like that” when Jim Krakouer was imprisoned for a series of sexual assaults and drug trafficking.

“There’s some memories I have: walking through a house that had been ransacked by police – that was sort of my first indication that things weren’t right, and being told that he would be going away for a while.”

He remembers going to see his dad, and “it was a bit of a process: you’ve got to sign in, and then you wait. You go through the metal detectors and the dogs do a bit of a sniff and search, and then it’s a long walk up to the visiting room. I was excited to see Dad, even if it was scary going in there. I remember looking at that door, waiting for him to come in. So I had a bit of a think about whether I wanted to talk about those things. I felt Jacqueline’s warmth and her energy. And I suppose she had a nice aura about her.”

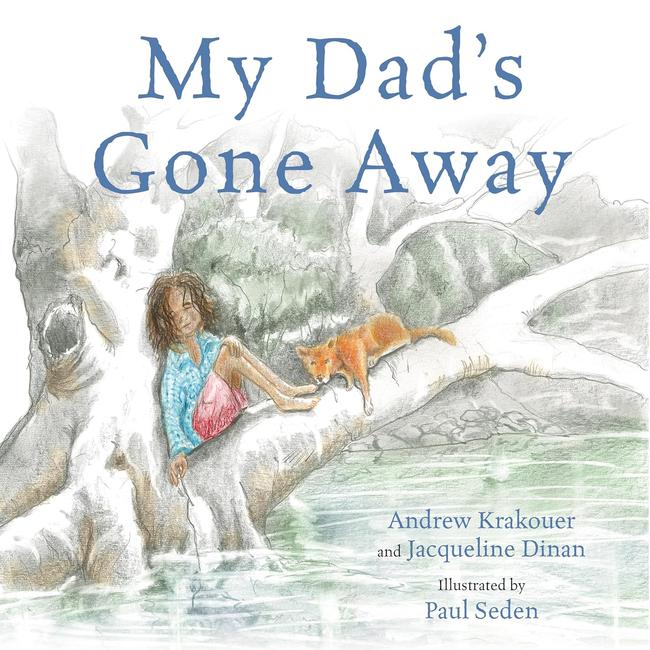

They agreed to collaborate, and the result is a tender picture book titled My Dad’s Gone Away. Dinan says the story is not Andrew’s but it reflects “his experience – the loud door, the visiting hours, the dogs – that helped us build the illustrations.” The book’s opening page says: “This book is designed to prompt children of incarcerated parents to talk about their worries … in addition to missing (mum or dad) the children deal with the stigma of having a parent in jail.”

It opens with a little girl called Tarah (her name is made up of letters from the names of Andrew’s daughters) who is wondering why she can’t find her dad. Has he gone “outback again, or shearing on some big sheep station”? She asks her mum, who says: “Tarah, your dad’s gone to prison. He had no time to say goodbye.”

One illustration shows the little girl watching as her mum gets security-wanded by the guards. Another shows a dog, “not looking for a friendly pat like dogs usually do”.

Andrew says: “In one of the pictures, the girl is poking her head around the door, and that captures how it’s scary for children.” The guard “searches them in case they are bringing in things that are not allowed,” and then BANG, a large door slams shut. When Tarah’s dad finally comes into the visiting area, he’s as nervous as she is. He’s wearing a green prison uniform, and he opens his arms wide for a cuddle, and his little girl runs to give him one.

Andrew says he’s apologised to his children “for what I put them through. I understand now that it’s called trauma. Probably when I was young, I didn’t understand what trauma meant, and how it impacted me. I did not understand they were going to be young women, and Aboriginal men are important role models, so important in their daughter’s lives. I felt I really let them down.”

Their mum, his partner Barbara Garlett, was immensely important to them, and she also agreed to stick by Andrew. Does he know why?

“Probably because her father had been to prison, too,” he says, “This was something we were all trying to understand.”

He knows that Barbara “could easily have decided not to stick with me, especially from her point of view, having everything going really well in our lives, and then all of a sudden, through a silly decision I made, I took everything away. I’m thankful every day that we’re able to, you know, stay true and still be together.”

Andrew says he understands as well as anyone “that if you break the law, you will be punished … but not everyone in prison is a bad person. I never necessarily thought I was a bad person. And I think another way to help people is to say, you have been to prison, that doesn’t mean you are a bad person. You can come out and do good things.”

He sees this book as his best shot at doing just that and Magabala Books publisher Rachel Bin Salle agrees, saying she is “honoured to publish” what she believes to be “one of the most important books of the year”.

My Dad’s Gone Away, by Andrew Krakouer and Jacqueline Dinan (illustrated by Paul Seden) is out on October 1. Teaching notes linked to the school curriculum are available on Magabala’s website.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout