Add this book to your must-read list

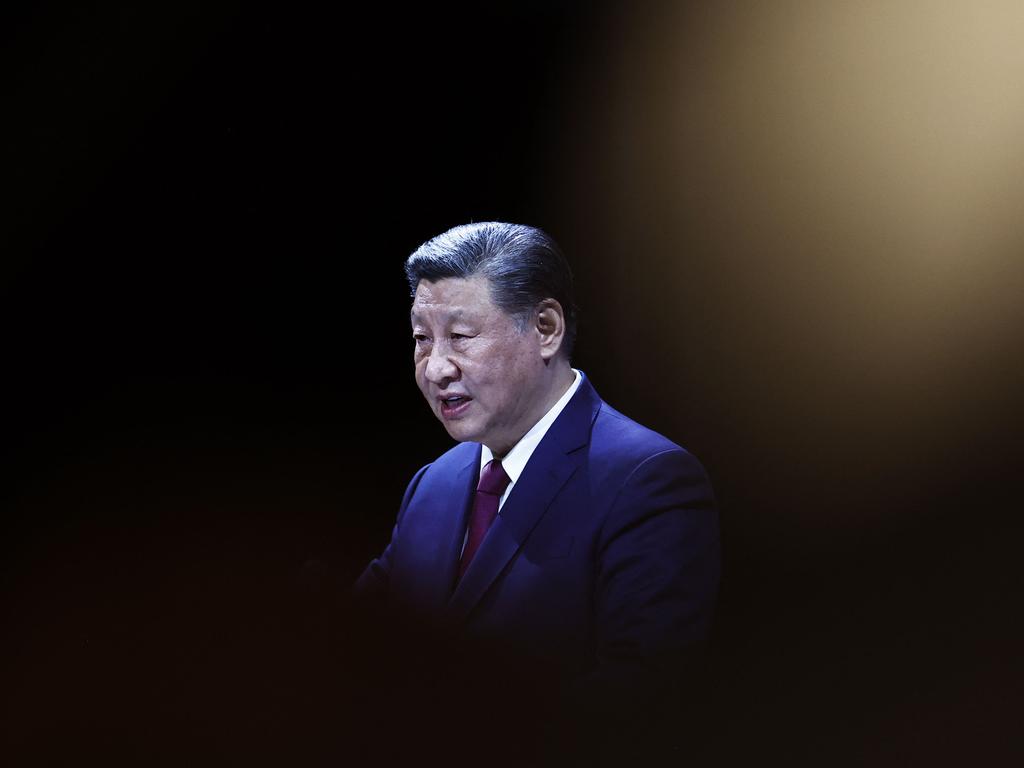

This story matters more than ever now, as Xi Jinping imposes on China the antithesis of what Hu Yaobang articulated and patiently, intelligently championed, between 1977 and 1987.

When I was invited, 25 years ago, to teach Chinese politics at Latrobe University, I was offered carte blanche to design the course as I saw fit. I opted to centre it on the life of Hu Yaobang (1915-1989).

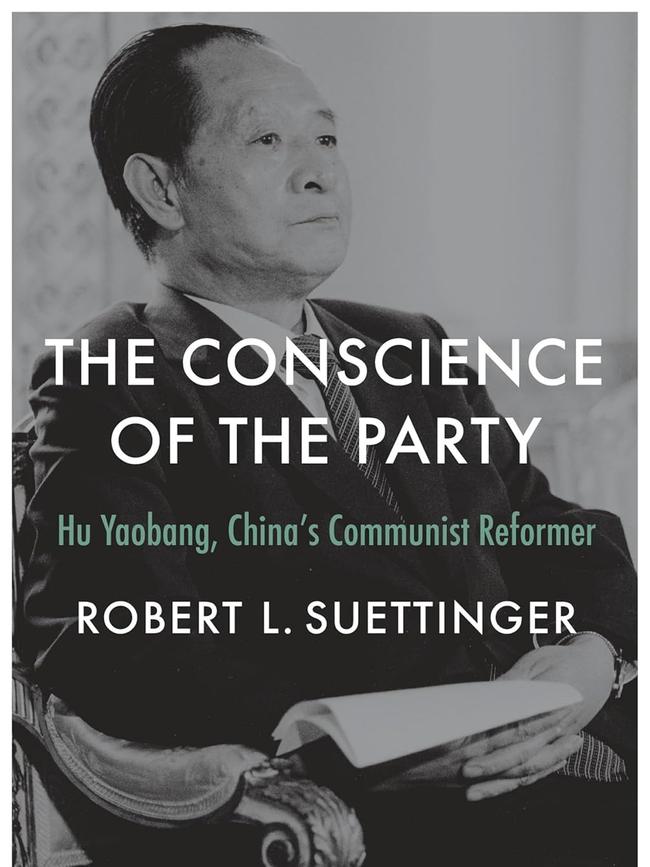

Five years ago, in Washington, I was invited to dinner by Dimon Liu and her husband, Robert Suettinger. Over that dinner, I learned that he was writing a biography of Hu Yaobang. As a 45-year veteran of CIA, State Department and National Security Council China analysis, he was well-placed to write such a book.

He has done a splendid job. If you feel the need to understand the origins, the history, the internal factional politics, the epic failures and current nature of the Chinese Communist Party, start here.

Suettinger titles his introduction “Soul of the Nation”. Why would he do that? Because Hu Yaobang embodied the sense of historical mission in Chinese communism; spent his entire adult life honestly attempting to fulfil that mission; and was the spear carrier, after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, for not only economic, but also political, judicial and cultural reform.

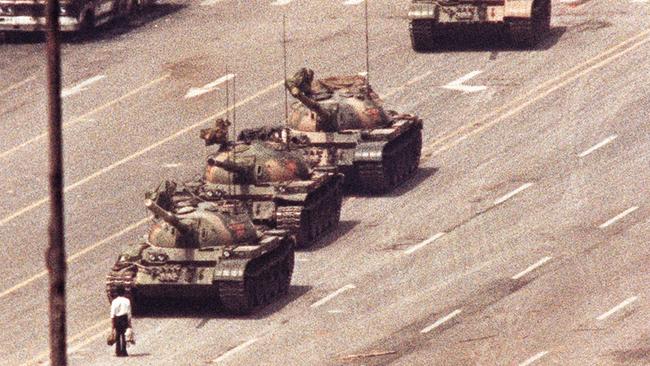

Widely read, Hu came to believe that China needed to replace Marx (to say nothing of Mao) with Montesquieu and responsible government. He was thwarted by reactionaries within the party and sidelined by Deng Xiaoping, from January 1987. His death, by heart attack, on April 15, 1989, brought tens of thousands of students and citizens into Tiananmen Square. There they placed Hu’s portrait on the Monument to the People’s Heroes. Deng Xiaoping declared martial law and sent tanks to forcibly clear the square.

This story matters more than ever now, as Xi Jinping imposes on China the antithesis of what Hu Yaobang articulated and patiently, intelligently championed, between 1977 and 1987.

A China which had embarked upon the path urged by Hu and many around him, would have been a China we could very comfortably and warmly have welcomed into the comity of modern nations. That of Xi Jinping we cannot, for it is opposed openly and aggressively to everything we cherish and live by.

Suettinger has laid this out for us in a beautifully balanced, poignant, deeply documented, scrupulously pondered biography. There are 10 chapters. The first three, “Born to the Revolution”, “Basking in the light of Mao Zedong” and “Winning the Wars, Securing Power” take us from the birth of Hu Yaobang to the overthrow of the Nationalist (Guomintang) government, in 1949. At that point, Hu was just 34 years of age, but already a bloodied veteran.

The next three chapters, “Growing Doubts”, “Into the Maelstrom” and “Cultural Revolutions” show Hu caught up in the vast excesses and catastrophes of the dictatorship by the party under Mao Zedong. They show him working under Deng Xiaoping in Sichuan in 1950-51 to secure that frontier province for the revolution, then running the Communist Youth League, then being deeply shaken by the Anti-Rightist campaign, again run by Deng Xiaoping, followed by the utter disaster of Mao’s Great Leap Forward, in which tens of millions of peasants perished; and, finally, being caught up and tossed about by Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

Even in the early years of the party, Suettinger shows, during the Jiangxi Soviet, the Long March, the years in Yan’an and the final phase of the Civil War (1946-49), Hu witnessed countless atrocities and abuses of power. In Sichuan alone, after the defeat of the Guomindang, while working for Deng Xiaoping, he was confronted by many hundreds of thousands of executions. But like all too many on the global left, he rationalised much of this as the cost of revolution.

His post-1949 experience changed that. After 10 years of torture and rustication, he emerged an articulate and gifted reformer and, championed by Ye Jianying, rose to become General Secretary of the party.

What he did and what he attempted in the final phase of his life (1977-1989) is covered in the final four chapters, “Bringing Order Out of Chaos”, “The Making of a Reformer”, “Deng’s Wrath” and “Hu’s Fall” and “Hu Yaobang and the Fate of Reform”. These chapters are luminous and elegiac. Xi Jinping would prefer they had never been written. You must read them.

There are major biographies of China’s modern leaders, starting with Mao. The best of these is Mao: The Real Story, by Alexander Pantsov and Steven Levine. There is Ezra Vogel’s bulky biography of Deng Xiaoping (Harvard University Press, 2011), which lionises him, and the more recent, more trenchant one by Alexander Pantsov and Steven Levine, Deng Xiaoping: A Revolutionary Life (2015).

There is a fairly thin biography of Hu Yaobang by Yang Zhong Mei, published English, in 2015. There is, also, the secret memoir of Zhao Ziyang, Prisoner of the State, smuggled out of China and published by Simon and Schuster in New York, in 2009. There are, also, fine biographies of Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo by Jay Taylor, which put all the pretensions of the Chinese communists in perspective.

None of these is so probing or so emancipating of the mind of the reader as The Conscience of the Party. Why? For two reasons: Hu Yaobang stands out among all his storied peers for his extraordinary capacity to rebalance and look ahead with integrity and never put personal ambition ahead of the core mission: modernising and liberating China.

There were others like Hu, of course. They were, all of them, crushed and suppressed, expelled or silenced by the party. For that reason and because of what has followed the killings in Tiananmen Square, including the crushing of liberty in Hong Kong and the ominous threats to Taiwan, this book must be read.

Read Josh Chin and Liza Lin’s Surveillance State: Inside China’s Quest to Launch a New Era of Social Control (2022) and Michael Sheridan’s The Red Emperor: Xi Jinping and His New China (2024). Absorb those books, then re-read Suettinger’s final chapter, “Hu Yaobang and the Fate of Reform”. This story is geopolitically vital now.

Paul Monk is a Fellow of the Institute for Law and Strategy (New York and London). He was head of the China desk in the Defence Intelligence Organisation in 1994-95 and is the author of Thunder from The Silent Zone: Rethinking China.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout