Academic reflections on Patrick White’s legacy

THERE is much to admire in a new collection of writing about Australia’s only Nobel laureate in literature.

NOT long ago, as an audience of would-be authors hung on her words, a literary agent told them who not to emulate. Patrick White was ‘‘overrated’’. His works would not find a publisher now.

Evidently she placed less faith in the judgment of the Swedish committee that awarded White the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1973 than in the experiment conducted by this newspaper in 2006, when the first chapter of White’s novel The Eye of the Storm (retitled with cyclone for storm) was sent to 12 publishers. Ten rejected it and two failed to reply.

Yet in 2009 the Louis Kahan portrait of White adorned the cover of The Cambridge History of Australian Literature and — together with Henry Lawson — he was the author most cited, and perhaps most highly valued there. Three years later, however, English novelist and sometime resident of Tasmania Nicholas Shakespeare mused in sorrow that White’s name was ‘‘temporarily and inexplicably lost’’.

This perplexing critical to and fro intensified in 2012, a year that saw the publication — against his wishes — of the purported first part of a novel by White called The Hanging Garden. His literary agent, Barbara Mobbs, had preserved a manuscript that White wanted destroyed. Thus a revaluation of White was given impetus in the year of the centenary of his birth (in England).

In December 2012, that anniversary was marked by a conference at the University of Hyderabad in India, run by the Association for the Study of Australasia in Asia. Evidently not without difficulty, or compromise, the proceedings of the conference, with contributions from ‘‘eminent professional observers of the Australian literary scene’’ from Australia and seven other countries, have been turned into a book by Cambridge Scholars Publishing (based in Newcastle-upon-Tyne rather than the Fens). This is The Legacy of a Prodigal Son, edited by Cynthia vanden Driesen and Bill Ashcroft.

To get the worst over with first, the publisher has done no favours to the many finely conceived and challenging chapters in this expensive book. The editing is a disgrace. A web search discloses testimonies such as ‘‘don’t expect them to do anything (even proofreading, publicity)’’. Nonetheless we should be grateful — with the reservations above — for what we have. These are contemporary and international responses to a cosmopolitan author who established himself as a great writer during an internal exile of 18 years on a 2.5ha block near the outer Sydney suburb of Castle Hill.

White had returned reluctantly to Australia after war service and a long period living in London and the US. His ambivalence towards Australia was linked inextricably with his dependence on it as his subject. The title of this collection comes from White’s famous polemic of 1958, The Prodigal Son, acerbic reflections on the country to which he had come home. However, as John Barnes writes in this volume, ‘‘no one killed a fatted calf on his return, but he became a literary hero, albeit an imperfect and imperfectly understood hero’’.

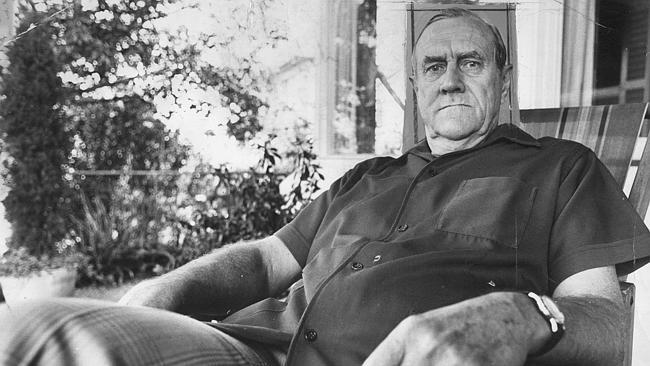

White looks out from the cover of this book with a gaze of stern melancholy. The image is from a black-and-white photograph by William Yang, who made a series of brilliant portraits of the author in later life. Some of them, as Greg Battye points out, purported to show White after his death. What would White’s wraith think of these conference proceedings? He had a visceral disdain for academics in general, and Leonie Kramer in particular, as expounded in his 1981 autobiography, Flaws in the Glass.

No doubt to his horror, he found himself enlisted for the purposes of Australian cultural diplomacy. His books became prime exhibits abroad, showcases of our artistic might. They were widely translated, too, although that is not discussed in this collection. Its editors find some justification for celebrating in India the centenary of White’s birth. The protagonist of his first published story, The Twitching Colonel (1937), was an irascible veteran of the Raj, while White’s first novel, Happy Valley (1939), had an epigraph from Mohandas Gandhi. Nevertheless, the efforts made in the section called Comparative Studies to broaden the subcontinental context are more compelled by good intentions than they are persuasive.

Barnes’s opening essay on ‘‘Australia’s Prodigal Son’’ introduces themes that are more central to the book, and more rewarding. As he recalls the last public speech by a frail White at La Trobe University in July 1988, Barnes, emeritus professor of English at that university, opens the discussion of White as a ‘‘public intellectual’’. This description is analysed by various contributors. The cause White espoused at La Trobe was that with which he was associated longest: nuclear disarmament. This was also the business of his overly didactic and recently revived play, Big Toys.

Pavithra Narayanan (Washington State University, Vancouver) contends that White’s ‘‘intellectual and public engagements … disrupted, disturbed and unsettled his audiences’’. Yet was the audience for his political pronouncements the same as his reading public? Was he regarded as an eccentric presence, a querulous curmudgeon unexpectedly come to grace the political stage, when his real agency of change was to be found elsewhere, in his fiction? As critic and theorist Ashcroft writes here, White’s work ‘‘is deeply imbued with a hope for what that society, a postcolonial new world society, could become’’.

The public business to which White came late on the platform, if not in his fiction, concerned Aborigines. No subject more exercises the contributors to The Legacy of a Prodigal Son. The point of reference is most often White’s most famous novel. (As he complained, ‘‘Why is it always Voss, Voss?’’) The explorer who wants to claim a continent by force of will is, notwithstanding, as Harish Mehta of Canada’s McMaster College argues, filled with ‘‘goodwill and empathy’’ towards the Aborigines who guide but eventually kill him.

White’s own contacts with Aborigines came relatively late in life. According to his biographer David Marr, there was almost none in the months that he spent as a young man on a relative’s property at Walgett in northern NSW. White’s sympathy with Aboriginal dispossession grew angrily (no works of his were to be published or performed in 1988, he instructed) yet — as indigenous academic Vicki Grieves argues — ‘‘it seems he had an affinity with Aboriginal spirituality but not unsurprisingly felt locked out of it’’. Wrestling with such paradoxes was, however, seminal to his art. This book explores in particular how White tried to make spiritual sense from what he called ‘‘the rocks and sticks of words’’.

What do academics do with their words, especially those who profess literature after the long blight of Franco-American theory? Its not unintended consequence was to alienate a generation of readers, at the same time as a handful of academics found a means of promotion. The authors in this collection sometimes succumb to jargon. Here is one left nameless: ‘‘This paper originates from an interdisciplinary non-binary critical approach, which applies Riane Eisler’s (1987) partnership model to world literary texts.’’

In the main, however the writers’ approaches have a humanist openness, an undogmatic spirit of inquiry. That this often leads them from the texts of White’s novels is maybe the price literary academics now have to pay for staying in work. The consequences are often enlightening, for instance in Kieran Dolin’s ‘‘Rewriting Australia’s Foundation Narrative’’, when he considers the fiction of White and Aboriginal author Kim Scott in terms of the Mabo case. That case, and indeed the history of government treatment of Aborigines, also features in the fine keynote address to the Hyderabad conference by former Aboriginal affairs minister Fred Chaney.

The Legacy of a Prodigal Son contains more conventional business, too: considerations of White’s treatment of ‘‘Language and the Sacred’’ by Lyn McCredden; Nathaniel O’Reilly on ‘‘The Myth of Patrick White’s Anti-Suburbanism’’; May-Brit Akerholt on the language of White’s plays and the ‘‘barren fruitfulness’’ of some of their female characters; Glen Phillips’s enterprising comparison of the early verse of White and Katharine Prichard in ‘‘The Novelist as Occasional Poet’’.

Another insightful comparison comes from Julie Mehta (University of Toronto) about three ‘‘Smelly Martyrs’’: White’s alcoholic Aboriginal painter Alf Dubbo in Riders in the Chariot, Velutha the Untouchable in Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things and David Malouf’s Gemmy in Remembering Babylon.

Nonetheless, in the book’s 33 chapters there are vital aspects of White’s writing that are not touched. Perhaps the contributors are too high-minded to consider White not only as one of the greatest Australian comic geniuses (a worthy companion to his friend Barry Humphries) but also as a prime exponent of the vibrant melodramatic tradition so important in the history of Australian fiction and drama.

More also might have been made of White’s influence on the next generation of Australian novelists, notably Thea Astley and Tom Keneally. In fact these qualifications indicate the capaciousness of White’s achievements, fairly but not comprehensively witnessed as they are in this stimulating collection of scholarship, theory, opinion and maybe less provocation than White deserves.

Peter Pierce edited The Cambridge History of Australian Literature.

The Legacy of a Prodigal Son: Patrick White Centenary

Edited by Cynthia vanden Driesen and Bill Ashcroft

Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 511pp, $150 (HB)