A walk in the (virtual) rainforest

A world-first immersive virtual reality experience, Gondwana is a love letter to the Daintree but also warning about its fragility.

Last month when federal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek released a dire report on the state of Australia’s natural environment, a report that the former government had kept under wraps, she emphasised how the Gondwana rainforests of the east coast were in peril.

Now a VR (virtual reality) project, Gondwana, focusing on Australia’s largest rainforest, the Daintree, by Emma Roberts and Ben Joseph Andrews, will be part of the Melbourne International Film Festival.

After presentations at numerous international events, including the Sundance and South by Southwest film festivals, Gondwana will for the first time be experienced in the manner its creators intended: as an immersive experience running continuously for 48 hours in a dedicated space at Melbourne’s ACMI.

Gondwana is a world first, says Andrews. “No one’s ever done anything like this before. There’s no durational VR.”

The Daintree Rainforest in north Queensland is unlike anywhere else on the planet. With rainforest meeting the sea it is the world’s oldest rainforest and boasts an elaborate ecosystem. Its biodiversity is astonishing, being home to a third of Australia’s frog, reptile and marsupial species, and 90 per cent of the continent’s bat and butterfly species.

Roberts and Andrews’ VR presentation is a love letter to the Daintree, but also a warning about its fragility.

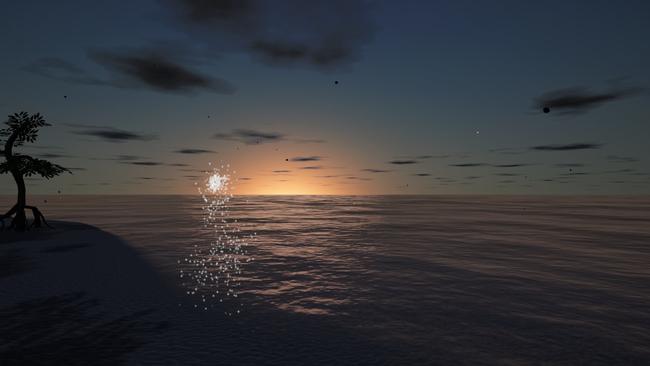

Like the rainforest itself, Gondwana VR is a system of possibilities. Weather, seasons and biodiversity shift and change. Wearing VR headsets, users can explore a vast environment of winding rivers, rugged mountains and ancient trees. But a broader narrative stirs below. Across 24 hours the rainforest degenerates, fed by climate data projections. Trees grow and die, and the seasons change. The event is unrepeatable and speculative – a meditation on time, change and loss in an irreplaceable ecosystem.

The idea is that visitors can drop in at any time during the 48-hour presentation.

Andrews explains that the presentation unfolds as a series of interrelated natural cycles, evoked through different layers of sound and vision.

“There are lunar phases, weather cycles, certain conditions that happen in the environment – the onset of bioluminescence in the forest only occurs if conditions of wetness and weather are met,” he says.

“Whenever we put the headset on, it felt like it had a life of its own. We want audiences to give themselves over and surrender to the experience knowing that you can’t fathom and comprehend all of the various things that are happening in the Gondwana experience at once.”

I had a personal reason for wanting to speak to Roberts and Andrews as I had been involved in the Daintree Blockade in 1983 when developers were keen to subdivide the area, and the Queensland government wanted to build a road between Cape Tribulation and Bloomfield.

A primary school teacher at the time, I had been part of a protest with local professionals, standing in front of a bulldozer at dawn after which we spent part of a day in jail. I mostly attended court hearings on behalf of protesters who had been arrested after chaining themselves to trees.

With the help of the federal government the Daintree, part of the larger Wet Tropics of Queensland, was listed as a World Heritage site in December 1988.

Roberts and Andrews are keen to hear of my experiences as someone who knows and loves the Daintree. The pair met when they studied film at the University of Melbourne, and went on to collaborate on several VR installations/performances, notably Moon Is Gone And All The Kings Are Dead (2016), commissioned for the 50th anniversary of the Victorian College of the Arts, and Starless (2017).

They first ventured to the Daintree in 2018 to prepare the Gondwana project, not really knowing what a magical place it is. They not only fell in love with the place but fell in love with each other and are now a couple.

“Working together deepened our relationship,” Andrews says.

They returned for six months in 2019, met the local people and camped in the upper Daintree River area with Aboriginal elders Mick Kulka and Ray Pierce, from the Kuku Yalanji tribe of whom Cathy Freeman is also a member. Pierce has since passed away, but his family has allowed the production to use his name.

“That was one of the most treasured experiences of my life because it allowed us to see the Daintree in this different, enlightening way – a new way of looking at the rainforest and the natural world,” says Roberts.

“The two (elders) and other family members were generous in walking us through their homeland, telling us so much about the ecosystem and the cycles and the cultural practices as well. It gave us this incredible perspective on climate change from a culture that has been tracking cycles and patterns and rhythms in the rainforest for thousands of years. They spoke about how the cycles are the way that you tell the weather, time and find food in the Daintree and that they are starting to fall out of sync.”

The filmmakers prefer the Daintree during the wet season when there are few tourists and the forest is strong and pristine.

“The wet always brings out so much life and so much more dynamism in the forest,” Roberts says. “To be in a place which is so wild and ever-changing, and to have that feeling of being in something that is 180 million years old is indescribable.”

The biodiversity is astounding, notes Andrews. “When we were up there the first time scientists had recently done a study where they dug up a cubic metre of soil and found around 1000 undocumented insect species,” he says. “So it just shows that it’s far from being completely known and they’re continually making many more discoveries. When we talk about the Daintree a lot of people know about the Great Barrier Reef, but they don’t know what the Daintree actually is.”

Gondwana has been picked up for the US by a VR specialist distributor and will be shown in many forms including dome presentations. Roberts and Andrews have since travelled to festivals in Europe and South Korea. After MIFF – they are proud that Gondwana will have its Australian premiere in their home state – they are looking forward to presenting the work throughout Australia. What will the effect be here?

“I hope the effect will be twofold,” Roberts says. “One is that it helps to reconnect us back to the beauty of our natural landscapes as Gondwana was always intended for a primarily city-based audience to remember what it feels like to be lost in an incredible and rich ecosystem.

“The other element is to bring some hope back to a discussion on climate change. That is something that was quite important to us as we created the project, because the data is very grim. The action from government and business doesn’t seem to match the urgency.”

She adds that just as the Gondwana VR allows users to allows users to cast an energy “fireball” that could preserve a tree during the simulation, individuals also have it in their power to make positive changes about the real-world environment. “The overarching message of Gondwana is that your small contribution, along with the small contribution of everyone who experiences the work together, is something that can make a difference to the outcome,” Roberts says.

“We didn’t want this degradation of the landscape to feel hopeless or inevitable – there is this larger message of what we can do about it. After the release of the government report and the data around it, we want to feel more hopeful about the future.”

Gondwana is showing at ACMI, Federation Square, Melbourne, from 12pm August 18 to 12pm August 20. An online version will also be available.