A Pair of Ragged Claws

Mirandi Riwoe’s Stone Sky Gold Mountain this week received the inaugural $50,000 ARA Historical Novel Prize.

“Hadn’t they been told that this southern land was a heavenly refuge? Heavenly. Conjuring up images of trees heavy with ripened peaches, pigs fattened and content. A land fertile with hope, yielding reefs of gold. Reefs. Layer upon layer of gleaming metal.” That is 19-year-old Lai Yue remembering what he and his 16-year-old sister, Ying Cheng, were promised when they left their financially disgraced family in China and headed to the Queensland goldfields. It is 1877 and they are in Maytown, once a hub of the gold rush, today a ghost town.

Lai, called Larry by the locals, and Ying, who must disguise herself as a man, are the siblings at the centre of Mirandi Riwoe’s Stone Sky Gold Mountain (UQP, 264pp, $29.99), which this week received the inaugural ARA Historical Novel Prize, worth $50,000 to the winning author.

The Australia Lai and Ying find is no heaven. “The land is barren, hardened, unwilling to surrender its fruit. The heat’s hostility is like a bite to the hand. And the white people. Those ghost people. Just as unwelcoming.” They are there, funded by a Chinese syndicate, which must be repaid first, to find enough gold to pay off their family’s debts, caused by their father’s gambling and opium addiction. Their only wish is to earn enough to return home. Their two younger siblings have been sold into domestic slavery.

This is a gripping novel from beginning to end. It shows a side of history I did not learn at high school. Brisbane-based Riwoe, who is of Chinese-Anglo descent, is a multi-genre writer. For her, one of the appeals of historical fiction is that it lets writers fill in the gaps. So it is that her main characters are the Chinese toiling on the goldfields and the women who work in Maytown, including the prostitute Sophie and her housekeeper, Miriem, who is a young woman with a troubled past.

Riwoe is brilliant at weaving rural Australia — its weather, landscape and animals — into the lives of the characters. Here is Miriem going about her morning chores: “She walks around to the front of the house and, as she passes a side window, she’s greeted by the sound of buttocks and thighs slapping against each other like fillets of chicken, Sophie’s work day had begun.” Here’s Ying finishing up from hers: “Even when she soaks her hands in the river water, she’s unable to rinse away all the dirt. She thinks that maybe she will be stained by this riverbed for the rest of her life.”

Lai and Ying struggle to survive. They have been at the goldfields for five weeks and are almost starving. Yet it is even worse back home. One day they are shown a Chinese newspaper, three months old. The main news is the famine, the desperation of people “eating roots and clay”. That line brings to mind Bruce Dawe’s poem The Not-So-Good Earth, in which an Australian family watches “25-inch Chinese peasant families / famishing in comfort on the 25-inch screen”. Uncle Billy, who has poor eyesight, uses the contrast knob to highlight the riot scenes, but this technological adjustment is less effective “on the quieter parts where they’re just starving away / digging for roots in the not-so-good earth / cooking up a mess of old clay”.

In Riwoe’s novel, everyone is a stranger in a strange place. It’s only a matter of degree. The “bloody Ching Chongs” are second-class citizens at best. The only people treated worse are the only ones who are not strangers in a strange place: Indigenous Australians. Some people consider the Chinese a threat, just as some people do today. The reasons are similar: there are too many of them and they want our natural resources, our space. Miriem thinks that “most of the time there seem to be more of them here than white people”. She has heard Cooktown is “even worse” and she is “not sure it should be allowed”.

She is not alone and it’s the coming together of two different races that drives Riwoe’s novel to its page-turning conclusion. There is suspicion, anger and aggression, but now and then there is also something rare, something close to friendship and affection, perhaps even love. This novel, like all good historical fiction, is about the then, the now and the future.

-

Today I want to mention three beautiful books about the non-humans with whom we share the planet. I’ll start with Animals Make Us Human, edited by Leah Kaminsky and Meg Keneally (Penguin Life, 258pp, $29.99). I’m extracting one of the pieces from it today, by the dad of one of the co-editors, Tom Keneally.

Tom, writing about echidnas, is one of several well-known authors who have contributed to this book, which does make me wonder about the correct collective noun. An anxiety of authors? There’s Ceridwen Dovey on koalas, Clare Wright on possums, Graeme Simsion on wombats, Robbie Arnott on thresher sharks, Karen Viggers, who is also a vet, on crabeater seals, Shaun Tan on red wattlebirds, Favel Parrett on lyrebirds and James Bradley on magpies. Every one of the 44 essays is worth reading and the accompanying photographs are spectacular.

Geraldine Brooks starts her appreciation of huntsman spiders in a way that shows why she has a Pulitzer Prize to her name: “I’m looking at him. He’s looking back. He’s looking down, in fact, from the ceiling of my bedroom. His eight-eyed stare is the last thing I see each night …” Paul Kelly contributes a song, Sleep, Australia, Sleep, that laments the animals we are losing. “Our children might know them / but their children will not.” Indigenous writer Kirli Saunders, in a poem from her new collection, Bindi, pays respect to the sacred garrall, the bird non-Indigenous people know as the black cockatoo. “We pause to hear her calls / from far away.”

Lucy Treloar and Chris Flynn each write about blue-tongue lizards, the only dual appearance in the book, and deservedly so. I fondly remember the blue-tongues of my boyhood. I also had a bearded dragon because my father, in his typical way, in the pub one night befriended John Cann, the “snake man” of La Perouse, and one thing led to another.

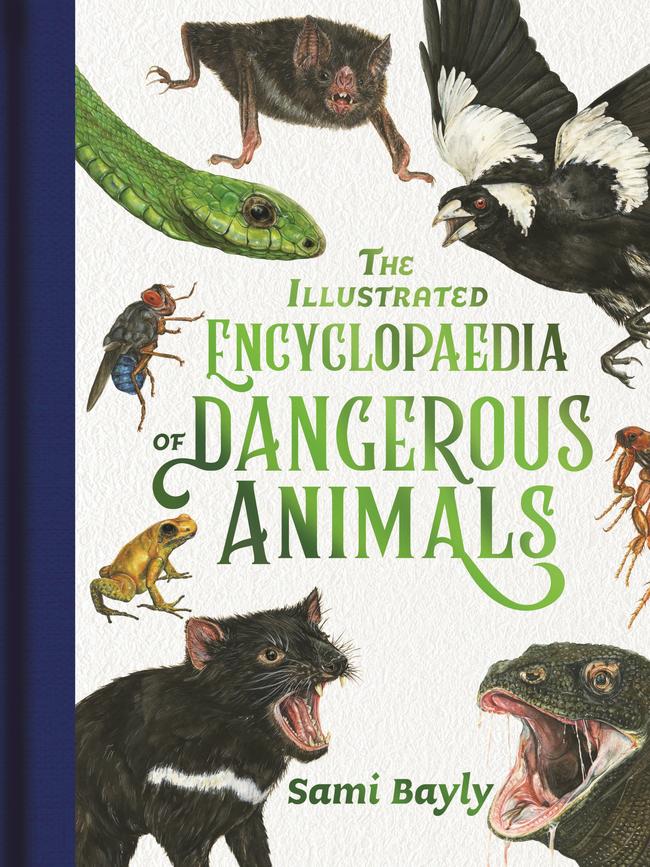

I love Sami Bayly’s The Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Dangerous Animals (Lothian Children’s, 127pp, $32.99 hardback) on several levels, including because it lets me dodge house rules and leave the “a” in encyclopaedia. This is a companion volume to Bayly’s previous book, The Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Ugly Animals. If you have an animal lover in your household, young or old, put both in the Christmas stocking.

The Newcastle-based writer and illustrator must have a lot of fun, and spark a few arguments, choosing which animals are “ugly” or “dangerous”. Ugliness is subjective, but dangerousness is a bit easier to pin down. As I skimmed the contents page, I thought: yes, maybe, not really, c’mon! I know cane toads, Gila monsters, Indian red scorpions, komodo dragons, hippopotamuses, electric eels, red-bellied piranhas, reef stonefish, shortfin mako sharks and southern blue-ringed octopuses are dangerous.

With others I can take a guess: golden poison frog, giant otter, oriental rat flea, red devil squid and one that ticks all the boxes, spider-tailed horned viper. But the greater slow loris? C’mon! It’s hardly going to run you down. So I looked it up and went straight to the box labelled “danger factor”. Well, it seems greater slow lorises produce toxin in glands located inside its elbows. So if you happen to meet one, be sure to avoid the social distancing equivalent of the handshake. The Tasmanian devil, long mischaracterised by Looney Tunes, is there. So is the rough-skinned newt, another animal with a bad rap. This newt can cause paralysis … if you eat it. Better off not doing that and having another drink instead. All newts will approve of that.

This book also returned me to my childhood. When I was a boy, my brother and I would go to Sydney’s Taronga Zoo to see one animal: the wolverine. This was back in the day of old-fashioned cages and while we stood outside the wolverine’s for as long as our parents would let us, we never sighted one. Perhaps that was for the best. As Bayly notes, the wolverine’s super strength and sharp teeth and claws mean “it is good to keep your distance and appreciate these animals from afar”.

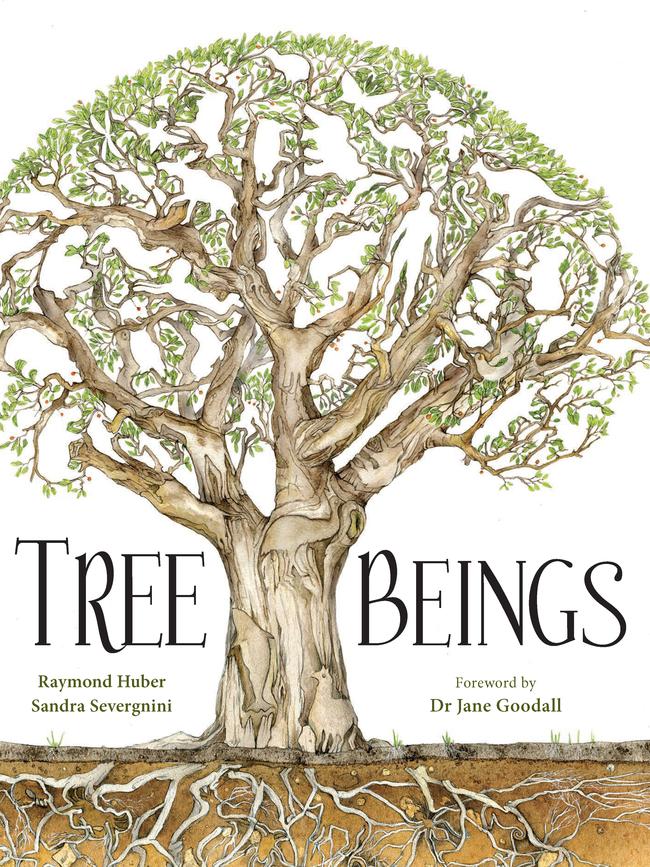

Tree Beings (Exisle, 96pp, $34.99 hardback) is by Kiwi children’s author Raymond Huber and Melbourne artist Sandra Severgnini. The book is aimed at schoolchildren but it is for all ages. It’s about why trees matter, has chapters like The Voice of Trees (aka the wood-wide-web) and Make Friends with a Tree and it draws on the work of pioneering tree lovers such as Richard St Barbe Baker and Julia Butterfly Hill. It opens with a foreword by Jane Goodall, who recalls her days studying chimps in Tanzania. “I got to know individual trees and I would greet them whenever I passed, pausing to feel the bark.”

Trees can be large, as can animals. They can also be small, like newts. I’ll finish with the opening to Nick Porch’s piece on a rare beetle in Animals Make Us Human: “Consider the little things.”

–

Tom Keneally’s love letter to ‘Australia’s groundkeeper’

I got to know echidnas only after I moved to Manly and became an habitue of the wonderful headland scrub of North Head. It is a place where on bush tracks, and sometimes on the street, you encounter them, these well-spurred, spiky balls of spines with what I find to be an amiable snouted face.

The snout is, of course, a birdlike beak to go with the other oddities of the echidna’s nature. Something about their humble, defensive imperturbability attracts me.

For longer than I like to confess, I mistakenly considered ‘‘echidna’’ an Aboriginal name, but no, she carries the name of the Mother of Monsters in Greek mythology, the half-human, half-snake woman. The human side of her is suckling, and the snake side of her is the small leathery eggs she lays.

She is an enduring mystery from the other side of the emergence of hominids. I call the echidna ‘‘she’’ because it’s a species in which the females have the best tricks, even if they are tricks not commonly visible to humans. And she doesn’t have the crowd-pleasing tricks of her fellow monotreme, the platypus, though we are told she can swim, especially if required to.

I say she has the best tricks even while acknowledging that the males have four penises, two of which they employ at the one time when impregnating a female and two of which they reserve for next time. A line of males will follow the female nose-to-tail for up to a month, tough work in the tangle of North Head, and then she will turn and mate through her bifurcated genitals with the male who lasts best and is able to neutralise other males with his poisonous spurs.

Within 10 days she will lay an egg, dropping it into a body pouch full of milk glands without teats.

The egg hatches and the hatchling stays in her pouch until maturity. At hatching it has no hind legs.

The small creature is called a ‘‘puggle’’, a name good enough to satisfy the euphonious wordplay of any child. You don’t often see a puggle in the wild, because she strictly keeps the child in her pouch, or, later on, her burrow, and discourages infant adventures.

Most interestingly, she has been found to have REM sleep. The echidna dreams. What is the echidna’s dreaming?

On a walk in the bush, on a morning full of the thick, particulate smoke of a burning country, and haunted by the global anxiety we felt that summer, I encountered one of the echidnas threatened, by both the fires and the state of the world, with extinction.

I love this creature: it gives off an air, despite its limited movement, of industry, and has the sort of waddle that in humans is the mark of elderly groundkeepers you have to charm before you’re allowed to do anything. As I met her that day, she was turning over the earth to the depth of her beak in her search for provender.

It was touching, of course, because she didn’t know she was in danger. I watched as always for the flick of her tongue, six to seven inches and lethally sticky to termites.

To see an echidna in the wild bespeaks how much human occupation, a tower of millennia, there has been in Australia, and of the contrast between Indigenous stewards and the stewardship of us immigrant groups.

Look at this busy survivor, who has been turning Australian soil for at least 20 million years, and one realises she has seen an unimagined version of our continent, has protected her young from the tread of the diprotodon, from the maws of the thylacine and the carnifex, the lethal marsupial lion, now extinct.

And in her august monotreme presence the news comes all the more forcefully that it has taken us less than two and a half centuries to bring the heroically surviving echidna, and the environment that sustains her, to crisis.

She doesn’t deserve it.

Name of her species: Tachyglossus aculeatus. Fast-tongued spiky. Australia’s groundkeeper.

This is an edited extract of Tom Keneally’s contribution to Animals Make Us Human, edited by Leah Kaminsky and Meg Keneally (Penguin Life, $29.99).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout