A message of love, beyond the grave

As a funeral director, Richard Gosling was sometimes asked to meet the person who would be in the coffin. Here, he recalls a tender exchange with a woman who did not want her children to worry about her after death.

I’m a firm believer that every call to our funeral home should be answered quickly. The phone shouldn’t ring for more than two chirps before one of us picks it up. Reaching out to a funeral home is the last thing people want to do. Emails should also be answered promptly.

“I want to talk to someone about prearranging my own funeral.”

That’s one of the messages I received. I copied the email address and wrote back, introducing myself and asking how I could help. The woman asked if I could come out and see her, and be discreet. I reassured her I could. She gave me the directions.

“Come through the gate, quickly through the gardens, and then you’ll need to buzz from the door.”

At the appointed hour, I found myself walking through her apartment complex, past neat hedges and windows. At the door, I buzzed, and a female voice answered. I introduced myself, and the door clicked open. When I got inside, the woman was sitting on a large and comfy-looking sofa by the window, with a blanket over her. She didn’t get up, and I bent to touch her hand as I said hello. Her skin was cool, and she pulled the hand back under the blanket.

I started my usual preamble about prearrangement and prepayment, but I could see she wasn’t listening. In fact, she looked for all the world like she was just having a rest, but then I realised she wasn’t. She was drawing near the end.

“I want to have everything in place for when it happens.”

“We can do that,” I said and took out my file. “We’ll need to start with the Births, Deaths and Marriages information that – ”

“And you’ll need for my death certificate.”

I nodded.

“I’m afraid so, yes.”

I wrote down the answers my client was able to five me: parents’ information, her place of birth, marriage history, and the names of her children. She smiled as she said each name, and asked me if I needed to know grandchildren and, though I didn’t, I let her talk me through them one by one.

“You’re a yiayia?” I asked and she smiled at me.

“I am.”

She let her breath slow for a moment. Then she told me her daughters lived in the same building and would chase me out if they knew I was there.

“They still think I am going to beat this,” she said.

“Well, maybe you will.”

She shook her head slightly.

“I won’t. But that’s OK. It’s OK now. If I can know this (funeral plan) is in place, then I will feel better.”

We worked through the details – the church and coffin and flowers – and then she asked that her family follow on to the crematorium.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes. I want my daughters to come to the crematorium with me.”

We talked for a little longer, her wanting to know how things worked when she died, who would collect her, where she would be held, how long after death the funeral would take place.

Then she talked about her priest and asked me to let him know about these arrangements but to ask him please not to tell the girls. I said I would try.

Then she looked at the clock and told me I should go soon.

“My girls will be coming back.”

I put my things away and stood. She stayed seated, and I walked over and held her hand again.

She said, “Thank you.”

I tried to find something I could say. “Stay safe and warm,” I said, and she smiled.

“Quickly, now. Off you go.”

The following day another email arrived from her. There was a Word attachment to it.

“I know this is asking a lot, but please would you read this to my family at the crematorium after the service? It would bring me peace if you would say yes.”

I opened the Word document. It was a love letter from a mother to her children and grandchildren and to her sons-in-law. Beautiful words that she wanted me to say on her behalf.

“Of course,” I wrote back. She replied with her thanks.

She faded from my mind, until the phone rang months later to tell us, at the funeral home she had picked for herself, that she had passed.

Typically, when we meet the family of a deceased person, we have maybe a minute to win their trust, to assure them that we can look after their mother, sister, daughter with safe hands and care. Walking back into my client’s apartment, her daughters now present, her brother there, all turning my way, I felt I was on the back foot. They could easily have a distrust of me, a suspicion that came from the fact that I had been here before, talking to their mother without their knowledge.

The corner where she had sat was empty now, and I sat close to where she had been, and introduced myself, explaining the situation.

“Mum met with you?”

“She did. I’m afraid she had me sneak in while you were all out. She wanted to set things down, and I don’t think she wanted to upset any of you.”

“You snuck in?”

“I know. It makes me sound like a cat burglar. She was very precise. She told me to arrive after such-and-such a time, park an unbranded car out of sight, not wear a uniform, come in through a specific gate. She chased me away at the end because she knew you’d all be home soon.”

They stared at me, and I expected to be called a ghoul and thrown out.

Instead, with a deep breath, one of the daughters asked me what was in the funeral arrangement. I talked them through it, step by step, and when I mentioned the priest, they said they would call him soon. I said I had already spoken to him some months before under their mother’s instruction.

“The priest is in on this?”

“He’s been praying for her.”

Then I told them about their mother’s desire for them to attend the crematorium after the church.

“With the priest?”

“No, just yourselves ... she has given me a letter that she wants me to read you all after the funeral service.”

“You’ve read it?”

I said I had.

There was a long exhalation of air in the room.

“And she planned all of this?”

I nodded.

“Then this is what we do – it’s what she wanted us to do. There’s nothing bad in the letter?”

“Nothing at all.”

Eyes watched me, and then they agreed, and they signed the papers I needed.

After the service, as friends gathered around the hearse, I explained to the crowd that the family would now be moving on for a private cremation, but that they were all invited to the wake.

We slowly drove across the city and pulled up precisely on time at the crematorium chapel. Our staff carried the coffin in, and the concierge asked me if there was music.

“No, just me - and a letter.”

Crematorium concierges have given me some of the most needed hugs I have ever had after particularly hard services.

Standing at the lectern, I introduced myself, and again explained to the children that their mother had me sneak into their building and plan her funeral out of their sight.

“Then, the day after we met, she emailed me this letter and asked that I read it when we reached this point.

“I have copies for you all once I have read it out.

“I hope this is OK with you all. Please forgive your mother’s words coming from a middle-aged man’s mouth.”

I unfolded the letter, which I had read aloud a few times to practise, so as not to stammer or mumble. Now, with her daughters in front of me, I found that I could barely say a word.

The letter was about nothing but love. Her love for them. Her joy for them. Her love for her sons-in-law, her grandchildren. She adored them all and wanted them to know it. Love, pure and beautiful, written from the corner of the sofa by a woman in her last days. A woman who wanted to know that, on the day her family said goodbye to her, she would have the chance to speak to them and reassure them, one last time, to tell them:

I love you.

I have loved you.

I will love you.

Always.

I reached the end of the letter and felt my hand shaking as I pulled some copies out of my pocket and stepped down to hand them over.

Thankfully, the family hugged me.

One of the daughters said, “You will never be hungry if you are near my home,” which remains, to this day, one of the greatest things that has ever been said to me.

To express love is a wonderful thing. We really should say it more often.

People tell me love stories nearly every day. They arrive and tell me how great their father was, how perfect their mother was. Beautiful wives. Handsome husbands. Perfect children. Longed-for babies. Such wonderful babies. Friends. Good friends. People who danced, painted, sang, flew, built, discovered, dreamt and loved. There is so much love in death. Pain, yes, terrible pain. But surrounding it, above and below it, is nothing but love.

I loved you so.

You’re gone, and I will miss you.

I will remember you.

Thank you.

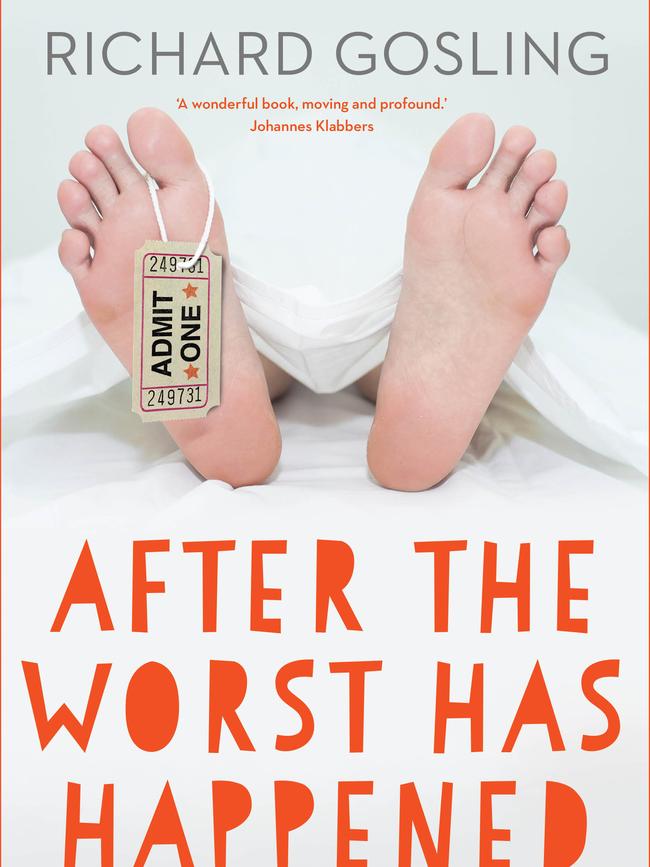

This is an edited extract from After The Worst Has Happened by funeral director Richard Gosling, published by Affirm Press and out next week

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout