A Hundred Years of Dirt: Rick Morton wrestles with a dark inheritance

Rick Morton wrestles with a dark inheritance in his funny, tragic account of growing up in outback Australia.

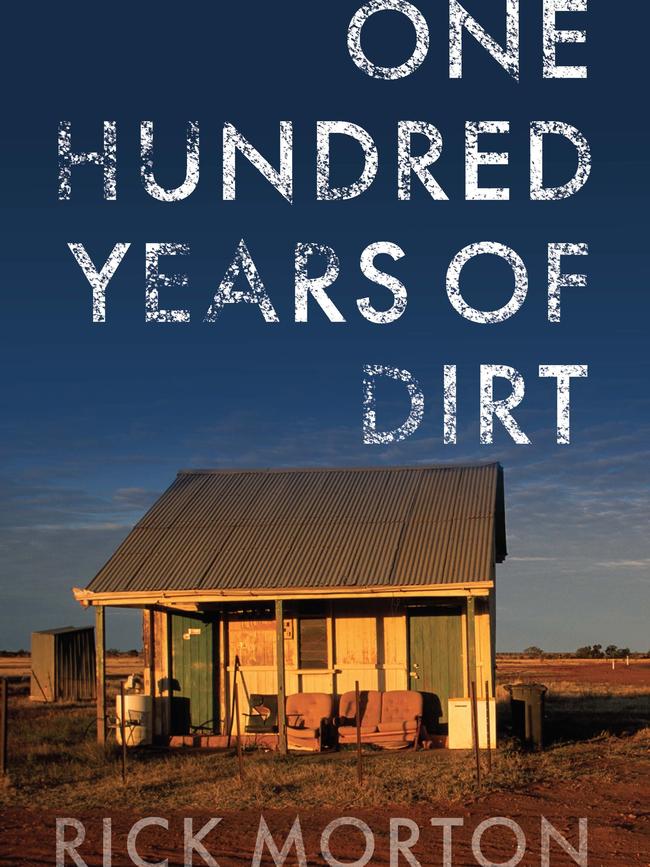

‘My sister Lauryn has taken up hunting wild pigs, which is a thing people do.” So begins Rick Morton’s irrepressible and improbable memoir One Hundred Years of Dirt, with a story readers will absorb in much the same way as they watched Doctor Who as kids: entranced, appalled, through a veil of fingers from behind the couch.

It is an arresting opening line, but not as comic as it sounds. In the world where Morton grew up, the world where his younger sister still lives, pig shooting truly is a thing that people do.

Morton, a reporter on this newspaper, may situate himself as an outsider in these early pages, describing his mounting horror at the bravery and warrior vigour demanded of him, a scribbler gone to seed during his years in the city, a gentle gay man dropped into a blokeish outback realm.

But what becomes clear is that One Hundred Years of Dirt is written by someone with deep knowledge of and an intense sympathy for the place and people about him.

If David Malouf’s idea of Australia is informed by the continent’s tropic east coast, its emerald verdancy, then Morton’s is characterised by red soil and endless blue skies.

This is the Channel Country of southwestern Queensland: the far side of the dog fence designed to keep dingoes out of the nation’s agricultural breadbasket. An empty, effectively lawless, violent and death-haunted region, in other words, yet also the place where, for the first years of his life at least, the author lived a remote, dusty idyll.

Morton’s memoir is the story of how that idyll ended in exile, poverty and domestic heartbreak. It is a tale filled with terrible news: one whose main redeeming feature, beyond the warmth, wit and savage honesty of its prose, lies in the definitive proof it offers that its subject made it through alive, though not without outbreaks of self-sabotage along the way.

The salient fact of Morton’s history is that his family was (and remains), for generations, at home in this hostile landscape.

A century back, Celsus Charles Morton arrived in the Birdsville region and began carving out a kingdom in the bush. Subsequent generations owned or managed huge tracts of agricultural land, albeit marginal country. At one point they owned a parcel of outback Australia the size of Belgium.

These men were more like 19th-century Russian landowners than English landed gentry. There was little opportunity for them to step back from hard work to indulge more refined activities.

They were ferocious workers and backblocks autocrats, constantly feuding among themselves, whipping their children and employees as though they were unemancipated serfs.

These were, Morton reports, the kind of people “who have the kind of resistance to natural forces that aircraft engineers look for in testing”.

By the time Rick makes his first appearance in the 1980s, the family has suffered for decades under the iron rule of his grandfather, George Morton, owner of Pandie Pandie station. Despite the drollery with which Morton drapes George’s story, the brutality of which the man was capable is stark. He beat his own daughter with a screwdriver to the point where she could not stand up; his sons slept under their beds of a night to evade the same treatment.

George’s wife, Lorrie, had nowhere to run. She was obliged to watch as her husband turned the children against one another and caused them lasting psychological and emotional harm. And no one of that younger generation seems to have suffered more than Rodney, the author’s father:

Most of the Morton men are barrels with legs. Their beer bellies surge out and hang below the waists of their jeans. They never learned to walk softly on this great Earth. My father was not any of these things, rather a throwback to his own grandfather. Scrawny and short, he could have been taken in a gentle breeze. His father called him Acre because they ran 1.6 million acres at Pandie Pandie and Rodney was a speck on it, so Acre he was.

Morton portions out this dark inheritance with such matter-of-factness that readers may overlook the point of the exercise. He wants us to appreciate the injury done to his father, so that we may accept with greater forbearance the injury he will inflict to his own family. Then, of course, there is the damage that the author will visit, later on, on himself.

Try as they might to contain the damage, it seeped through, father to son and father to son. Desolation moved like a slinky through them all.

First, though, there are the few, good, early years. Rick and his older brother, Toby, grew up in the late 80s and early 90s on a station so remote that Burke and Wills met their end in the region. The danger inherent in living at such remove from ordinary medical care is brought home when, one day, while in a shed, six-year-old Rick is there when his brother is accidentally set on fire:

In my mind there is no middle, just a jump cut to the frantic rush to the homestead.

It was Father’s Day, and there was Dad, cradling Toby in his arms while skin hung from his son like curtains.

The kicker comes when Rick’s mother takes the Flying Doctor flight alongside her desperately ill son, carrying her newborn daughter with her and, in the interim it takes for the treatment to stabilise Toby’s condition, the boy’s father begins an affair with the children’s 19-year-old governess. It is cruelty piled on top of tragedy and it inevitably leads to break-up. “Acre” Morton and his new partner head one way; mother Deb and her three children head to a housing commission place in Charleville.

Even a long review can do bare justice to the crappy things that happened to Rick Morton and his newly constituted family in the years that followed. The man who had spent years physically and emotionally abusing his wife then cut her off, often not even meeting basic child-support payments.

Morton is at his most ferocious as a journalist in those parts of the book related to the working poor in rural and regional Australia, and we trust him because he has been there, a boy trying to placate his hysterical mother after leaving a light on because even a few extra dollars on a power bill might be the difference between poverty and utter penury.

How Morton managed to escape this life is partly a testament to his mother’s scrimping and saving, and partly a case of talent winning out, but it is a close-run thing nonetheless. Brother Toby becomes involved with drugs and ends up in jail while Rick, an anxious boy who is already aware that to be homosexual in a country town is not a choice available to him, somehow finds his way to Bond University on a scholarship of sorts, and then on to journalism, albeit via a circuitous route of screw-ups and breakdowns.

Morton drinks too much and makes poor life decisions; he is a financial basket case. Somehow, though, through a cussed, crazy, razor’s-edge progress, he ends up making a career for himself, first on the Gold Coast and then in Sydney. This is not a book about success, however. It is the account of a man who has carried large amounts of accumulated hurt into adulthood, then fought tooth and nail not to be undone by it.

Nor is it even wholly a memoir. Very little of the author’s past is more than sketched in these pages. Morton’s illustrious and monstrous forebears are mopped up with an anecdote here and there; his school years are passed over in pages. Only stray wisps of family life are touched on for their own sake.

Instead Morton has sought, where possible, to tie his experience to wider social issues. He cites academic studies and statistics, relays anecdotes and cautionary tales culled from his years as a journalist. He rails against those professional right-wing contrarians who presume to speak for the poor and marginalised of country Australia while pulling in urban media salaries. He also accuses the left of ignoring the pain that, say, increased energy prices have on the same benighted groups.

Morton may do it with a wink and a one-liner, but much of this account is given over to a furious editorial against a blind and self-regarding coastal elite.

That he includes himself in this general condemnation is what returns us to the personal. Morton articulates, with passion and unrelenting autocriticism, his sense of culpability and shame. His is a Gordian tangle of childhood trauma and sexual confusion, survivor guilt and substance abuse.

It would be a short life, impossible to assimilate, were the author to play it straight.

Rather, his genuine love for family and friends, his gleeful self-awareness, even when caught in the trap of mental illness — his comic verve, which shines off every page — bears him and the book aloft.

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

One Hundred Years of Dirt

By Rick Morton

MUP, 192pp, $29.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout