Personal journeys into dementia cause for society’s concern

People with dementia describe their experience in a moving performance with the Australian Chamber Orchestra.

As Nell Hawe will tell you, she doesn’t look like someone with dementia. She’s too young. She has a bright personality. She wears fashionable shoes and has fancy nails.

Yet Hawe, 55, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease three years ago. For four harrowing years before that, she’d experienced the signs and symptoms of dementia, but the doctors she consulted put it down to stress.

Hawe had spent her working life in aged care and assessment, including care of dementia patients, so she knew what she was looking for. Memory loss. Writing notes and setting alarms on her phone to remember things. Forgetting where she’d hidden Christmas presents.

Her diagnosis in 2020 came as a relief: at least she now knew what was wrong. Hawe lives in her own home and has the help of support workers. But the disease has affected her vestibular system and sense of balance, and she has to use a wheelchair when outside her home. And dementia has come with significant personal cost.

“I lost my marriage. I lost my friends. I lost my work life. Lost my driver’s licence,” she says. “But it has opened many doors.”

Last year, Hawe became involved in a theatre project to document people’s experience of dementia and to share their stories with others.

To Whom I May Concern is a form of verbatim theatre. Across several months, the participants took part in group conversations, after which their stories were recorded and scripted as “letters” addressed to friends and loved ones. In the performances, each of the participants reads their letter aloud.

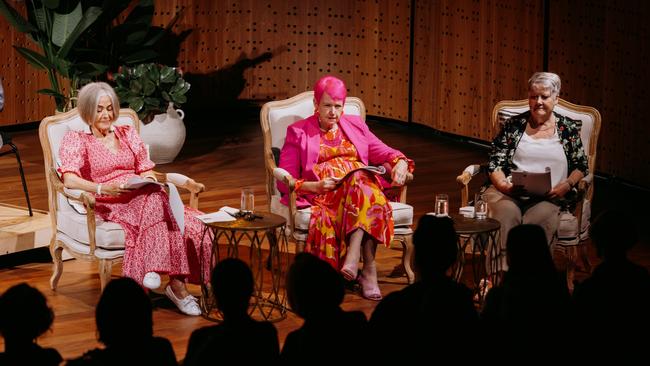

The project was presented last year and returned for two performances last week, at the Australian Chamber Orchestra’s Neilson studio, at Pier 2/3 in Sydney. Six people with dementia – Susan, Gwenda, Dennis, Bobby, Val and Nell – read their letters in the hour-long show, with musical interludes provided by five musicians from the ACO.

I don’t expect to see many shows this year as important, affecting and beautifully presented as this one. Everyone’s stories are individual, uniquely their own. And yet there are similarities, shared experiences of living with dementia.

Susan, who introduces the performance and sets the scene, describes her experience of a planned visit to the Sydney Writers Festival with a friend, and the comedy of errors that ensues. Missed trains. A lost phone. A dash home and getting the car. No parking spots. Defeat. “The friend, a loving loyal friend, said, ‘Everyone has days like that, Susan’,” she says. “Well, no they don’t. Not as often as I do.”

Bobby, a psychologist, says she was used to having a busy life, working with clients, able to multitask and handle almost anything. “I was competent, organised, and you might say a bit anal. Then I couldn’t organise my work, I was getting confused, I couldn’t remember people. I thought I was tired and burned out. I retired but things didn’t get better. I could talk to one person, but following a conversation with two people, not at all.”

Eventually, Bobby was diagnosed with frontal lobe degeneration, but doctors and specialists didn’t bother to explain the condition to her.

“Was anybody ever going to tell me?” she says. “Dear doctors, it does matter. I need to know that it’s real, and what I’m experiencing isn’t imaginary, and I’m not going mad, and I’m not just making it up – even though I wish I was.”

While the speakers are reading their letters, silvery light from an overcast day filters through upper-level windows. As each speaker finishes, the musicians play a brief movement from a string quartet, or a piece with piano. The musical choices are not bright or effervescent, but are gentle and have a slightly melancholy tone.

Gwenda describes the experience of personality change: moods that come out of nowhere, the feeling of not caring. “Dear Empathy,” she begins, “Why did you leave me? Because you left me, I don’t care any more … I wondered: how much of how I behave is me, and how much the disease? I recognised that I just stopped caring. I just don’t give a shit about anything. It’s emotional blunting. I went through a lot of grief for the loss of the person I was.”

To Whom I May Concern was developed by Maureen Matthews, a nurse and psychotherapist in the US who has worked with dementia patients. What makes the Sydney performances really special is the addition of music, and the classy surroundings of the ACO’s Neilson studio. This wasn’t a meeting room with plastic chairs, or an aged-care facility, but a professional theatre with proper seats, lights and amplification.

The live music reminds us we are in the realm of people’s emotions. It calls us to listen, to attend to their stories. I watched Hawe during one of the interludes, smiling and nodding her head to the music’s gentle rhythm.

The two performances were presented by Group Homes Australia – a company that offers home-style accommodation for people with dementia – with support from the ACO, Dementia Australia and the University of NSW. Group Homes founder Tamar Krebs says she would like to take the show to other cities including Canberra, so politicians and policymakers can see it.

She makes the point that people can live with a diagnosis of dementia for many years, in their own homes and active in the community, before they need fully supported care.

They are the “invisible cohort” in public discussions about dementia.

Here are some things I learned. Dementia is a disease, not a normal part of ageing. The term covers about 150 different conditions, including Alzheimer’s, mild cognitive impairment and frontotemporal dementia. With most conditions there is no known cause, and no cure. Dementia is not usually hereditary, yet a diagnosis can profoundly affect the family and friends of those with the condition.

Hawe says she wants to educate people about dementia, and destroy the stigma and misconceptions that surround it. The brave people who took part in To Whom I May Concern deserve to be more widely heard.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout