Paul J. Greguric: homelessness to JF Archibald biographer

Paul J Greguric was living at a men’s shelter when he started work on his biography of JF Archibald, The Man Behind the Prize.

Two years ago, Paul J. Greguric was an author in search of a story. He was working on a novel about the time he lived on a rice farm in Thailand, but hadn’t been able to find a publisher.

As was his habit, he would write during the morning at the State Library of NSW, and then walk to the Matthew Talbot Hostel in Woolloomooloo, where he was living at the time, for lunch.

One day on his walk back to the hostel, he noticed banners flying outside the Art Gallery of NSW, advertising that year’s Archibald Prize exhibition.

It struck him that while many people have heard of the Archibald Prize — that annual collision of portraiture and celebrity — little was known about the man JF Archibald: founder of The Bulletin, early publisher of some of Australia’s canonical writers, and donor of a magnificent fountain in Hyde Park.

He looked up Archibald on the hostel computer and found that the last biography of him was Sylvia Lawson’s The Archibald Paradox, which was published almost 40 years ago.

“I needed another writing project, but I had nothing to go on,” Greguric says. “I thought, it’s time for someone to write JF Archibald’s life story.”

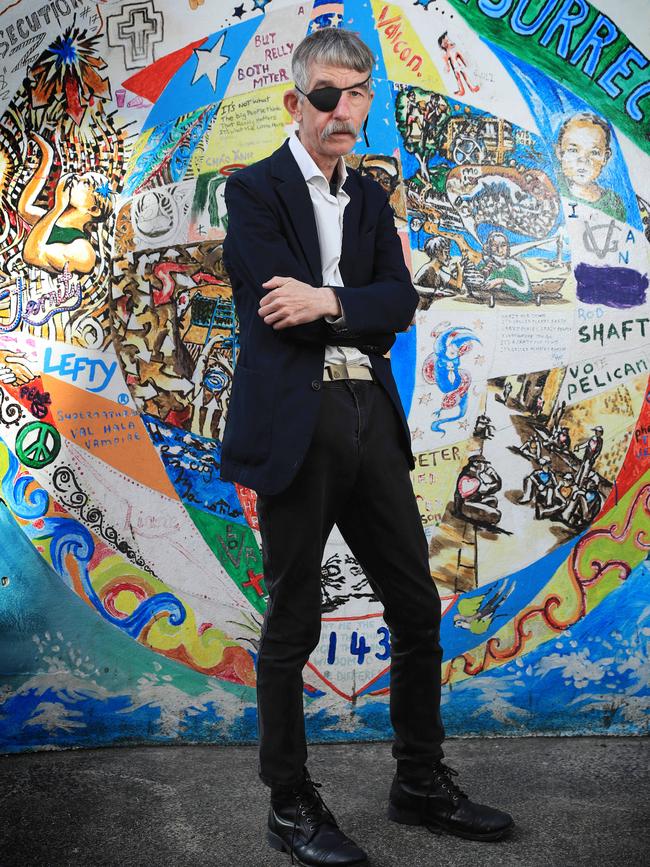

Greguric, 57, is slightly built, has a shaggy moustache, and wears a patch over his right eye. He had been an English teacher at a Sydney high school and long held aspirations of becoming a full-time writer.

On New Year’s Eve in 2010, he was attacked on the street and lost his eye, spending a month in hospital. He wears the eye patch, or sunglasses, to hide his disfigurement.

“You can say I’ve struggled with alcohol in the past, especially after my wound,” he says.

“When I was a teacher and this hadn’t happened, I was just a bloke who went to the pub. After this wound, I was using alcohol at times as a coping mechanism.”

Booze got the better of him. When he could no longer pay the rent at the hotel he was living in, he became effectively homeless.

He went to the Matthew Talbot because it offered accommodation to single men, and because he’d been told the food there was better than at some other places. A bed usually is available for three months, but Greguric stayed for 12, from August 2017 to August the next year.

“I slept in a dorm with about 50 men, homeless men,” he says. “I started writing a book about living on a rice farm in Thailand. My routine was to have breakfast at the Talbot with the men, then carry my laptop to the State Library. From 9am to 11am I would write this novel, then I’d come back to the Talbot for lunch. But after I finished the book, no Australian publisher would touch it. The publishing industry didn’t want to know me.”

J.F Archibald gave him a new project, and a renewed focus. The story that unfolds itself traverses struggle, personal cataclysm and ambition.

Archibald’s papers are held at the State Library and the research librarians there helped Greguric dig deep into the archive. Among the papers he inspected was a handwritten card recording a complaint from Archibald’s half-sister that Archibald had changed his given names, from John Feltham to the more exotically francophone Jules Francois. “That was the beginning of my detective work,” Greguric says.

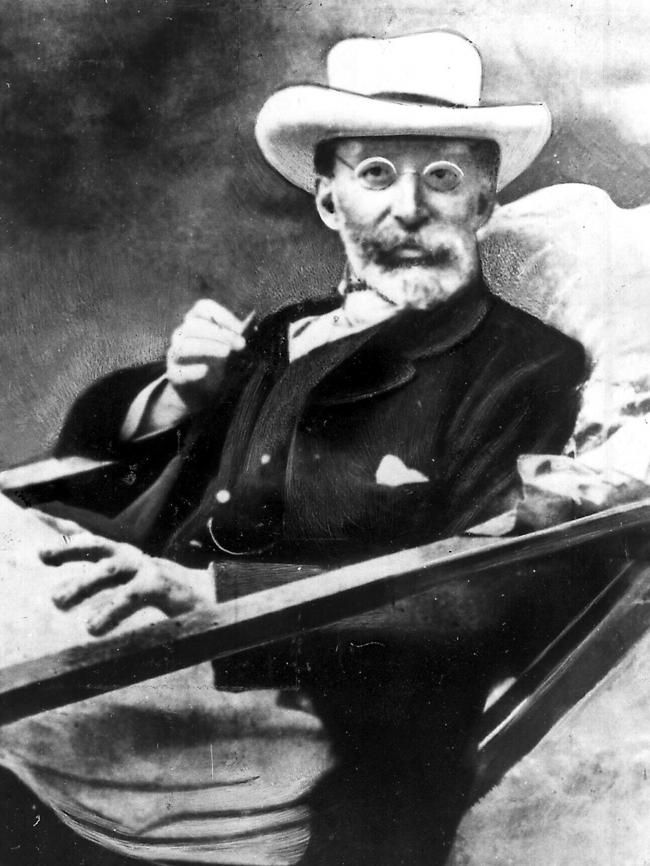

John Feltham Archibald was born at Kildare near Geelong in 1856 to Joseph and Charlotte Archibald. Joseph was a policeman on the Victorian gold fields, escorting gold on its perilous journey from the mines to Melbourne. Charlotte gave birth to five children and died when John was four years old. He was raised by Charlotte’s sister, Agnes.

At 15 he started in newspapers, first as a compositor (typesetter) at the Warrnambool Examiner. He submitted articles to the colony’s newspapers and landed a job at The Melbourne Telegraph covering the police courts, including a report on an execution at Pentridge Prison.

In Greguric’s account, Archibald was a skilled compositor and swift with a shorthand note, but he did not have the same early success as other young reporters his age. By the time he was 20 he quit newspapers and worked in the public service. And there were other distractions.

“When he was in Melbourne he appears to have fallen in love with a visiting singer, called Carrie Godfrey — I found a photograph of her,” Greguric says.

“This was when he changed his name from John Feltham to Jules Francois. He changed his identity from Roman Catholic to Jewish, and he became a francophile.

He appears to have followed the singer and her vaudeville troupe to Queensland, where he was heartbroken. Then he went to Sydney and attempted to go back into journalism.”

Sydney was where Archibald found success and, eventually, wealth. He became friendly with journalist John Haynes, and together they founded The Bulletin, publishing their first issue in 1880.

Archibald’s talent came to the fore as an editor and publisher whose magazine was vigorously nationalistic and republican — although it also fanned prejudices against non-white immigrants and Aboriginal people.

“He was very good at selecting pieces that he knew would interest people — everyone from the drover’s wife to the local schoolteacher,” Greguric says.

“But The Bulletin was shunned by the upper middle class and what was called the resident aristocracy.

“I read hundreds of editions of The Bulletin, and more often than not, it was the aristocracy, the monarchy, that was mocked and attacked,” Greguric says.

Disillusioned with the direction The Bulletin was taking, Archibald stepped down as editor in 1902.

By now he was comfortably off and started another periodical, The Lone Hand. But his mental health went into decline. Greguric says he would be diagnosed today with bipolar disorder — and in 1906 he was admitted as a patient to Callan Park Hospital for the Insane.

Although he suffered relapses, Archibald recovered his health and reinvented himself as a patron of the arts. He became a trustee of the Art Gallery of NSW and built a substantial personal collection, including paintings by Streeton, Heysen, Lindsay and Longstaff. He also encouraged the work of Hobart-born portraitist Florence Rodway, who would later paint Archibald’s portrait and enter it in the inaugural Archibald Prize in 1921.

Archibald left ample mysteries for a biographer. Greguric says he had several “Rosebud” moments during his research, a reference to the enigma uttered by the fictional media proprietor Charles Foster Kane in Citizen Kane. A daguerreotype in the State Library shows a young woman with a child, and carries a title indicating the picture is of Archibald as a young boy with his aunt, Agnes. A handwritten note accompanies the photograph: “Have pursued a shadow all these thirty-five years.” Who or what was the shadow, and whither the pursuit? Adding to the mystery, Greguric says the photograph is not of Agnes, but of Archibald’s mother, Charlotte.

“Either journalism was the shadow he pursued, or the memory of his late mother and his aunty,” Greguric says. “It’s a mystery. No one will ever know.”

Nor is it clear exactly why Archibald left a tenth of his substantial estate to establish the Archibald Prize. When he died in 1919, his bequest required that the prize be awarded for a portrait “preferentially of some man or woman distinguished in art, letters, science or politics”.

Archibald evidently had an interest in art and in the meritorious people of the day, but the bequest is opaque on other matters — such as whether the prize was intended to build a portrait collection.

Greguric completed his biography in about 18 months. He worked as he did before, writing in the mornings at the State Library and then going to lunch at the Matthew Talbot, even after he moved out of the hostel and into a boarding house.

There was some incredulity around the hostel — fanciful stories are not uncommon there, Greguric says — when he told people he was writing a book.

“I think they thought I might have been making it up,” he says. “Being a writer was like being a very lonely detective. That’s what it felt like. I’d walk out of the library in the afternoon and have nobody to discuss Archibald with. I had to do it on my own, and I hadn’t found a publisher either.”

Greguric did find a publisher, independent imprint Shawline Publishing, in Melbourne. His biography, The Man Behind the Prize, will appear in print two years after Greguric saw the banners flying and just in time for this year’s Archibald Prize — its centenary.

Greguric says he wants to return JF Archibald to the national narrative — not only for the Archibald Prize and the Archibald Fountain, but as a visionary magazine publisher who helped shape Australia’s literary culture around the time of Federation.

“If it wasn’t for Archibald, Banjo Paterson would never have been published, Henry Lawson would never have been published, and Miles Franklin was first reviewed positively in The Bulletin,” Greguric says. “It’s a wonderful, beautiful legacy.”

The Man Behind the Prize, by Paul J Greguric (Shawline Publishing, $22.94, from Booktopia)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout