Margaret Olley's studio could live again

RATHER than a museum, the late painter's home should become a residence for working artists.

THE last time I saw Margaret Olley at her home in Sydney's Paddington was in April, a few days after the portrait of her by Ben Quilty won the Archibald Prize.

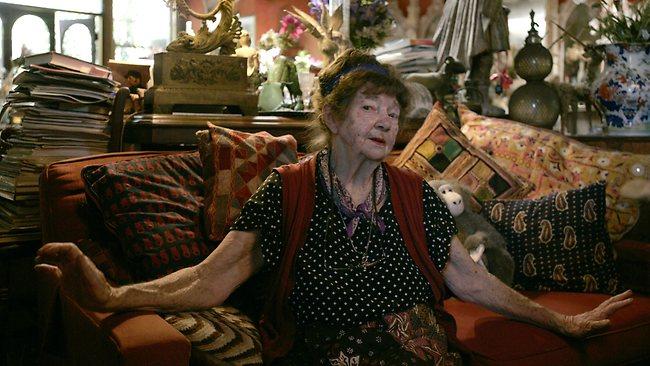

As on the previous occasions I'd been fortunate enough to visit, I entered the old hat factory studio by the laneway door and stepped gingerly through that abundantly furnished and chaotic room - always worried I'd knock something over - to Olley.

She was sitting near the courtyard doors where the light was good and she was working on a painting: a still-life of flowers for the exhibition that was due to open in September. She had a ciggie in her hand and was drinking the murky concoction that she called her amino acids.

Olley in her element was a wonder to behold: a small but commanding presence in a swirling microcosmos of beautiful objects and junk, the heady smells of cigarette smoke and oil paint, and always classical music on the radio. On this day it was playing orchestral excerpts from Tristan and Isolde, so the sensory overload was nearly complete.

She wasn't much in the mood for talking. Her health hadn't been good and the Archibald business had been a distraction from her work. She wanted to paint and I sensed her impatience to be getting on with it.

When she died on July 26 she had all but completed the final work for the exhibition: a large painting of her "yellow room", with its Matisse poster, fireplace, oriental carpet, and a table with a ceramic jug. The painting described the domestic interior: life in the Olley house was art, and art was life.

A state memorial service for Olley will be held at the Art Gallery of NSW tomorrow, with speeches by the Governor-General, Quentin Bryce, and others, and performances by the Australian Chamber Orchestra, didgeridoo player William Barton and pianist Alexey Yemtsov.

After that, discussions may turn to how Olley can be given a lasting memorial. In one sense, there are already so many: her paintings, and the many other artworks she had, over time, given to state and regional galleries. Indeed, all of her earnings went into the Margaret Hannah Olley Art Trust which - together with Olley's personal gifts - donated more than $10 million.

More vexing is what to do with her property at 48 Duxford St, the terrace house and adjoining hat factory. There is general agreement that this unique corner of Australian art be saved in some way, entire or in part. Author David Malouf and artist Cressida Campbell, for example, believe the house and contents should be preserved in situ. Others, including Olley's executors Philip Bacon and Christine France, seem to favour a display of Olley artefacts in another gallery or institution.

The nation could do something special. Some of the best places in the world for experiencing art are not the great encyclopedic museums but intimate house-museums where an artist lived and worked: the London home of neoclassical architect John Soane, for example, or the Long Island, New York house and studio of Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock, where Blue Poles was made.

The most meticulously preserved artist studio, though, must be Francis Bacon's at Dublin City Gallery, The Hugh Lane. Bacon's studio at 7 Reece Mews in London was even more chaotic than 48 Duxford St. In 1998, archaeologists moved the entire studio - more than 7000 items, including the door, walls and ceiling, as well as photographs, scraps of paper, paint tubes, books and records - to Dublin, Bacon's birthplace.

Within a few kilometres of Olley's place in east Sydney are several artist houses, and their example may be instructive. The missed opportunity is the house Patrick White and Manoly Lascaris shared at 20 Martin Road, Centennial Park. Efforts to save it for the nation as a study centre came to nothing, and the house is now in private hands with a plaque on the fence. The property is listed on the State Heritage Register.

Not far away in Surry Hills is the Brett Whiteley Studio in Raper St, a fascinating display of the artist's life and art. His studio upstairs has been preserved in a roped-off area, with canvases and brushes, a divan in the corner, walls stuck with postcards and photos and Bob Dylan playing evocatively on the sound system.

The property is owned by the Brett Whiteley Foundation and managed by the AGNSW; it is open at weekends and sponsorship from investment bank JPMorgan keeps admission free.

Would such a set-up work for the Olley house? Several people have described it as a living work of art, even as Olley's most original creation: a layering of detail and texture built up over the years.

Campbell understands, possibly better than most, its art-historical value. The subject of Campbell's art, like Olley's, is domestic interiors and still life, although Campbell makes exquisite woodblock prints while Olley painted in oils.

Olley has left, in several places, the arrangements of flowers and vessels that she painted in her still-life pictures. An earthenware jar with a branch of pomegranates, now dry, brittle and brown, remains near the window where she painted it. It is this context, Campbell says, that makes it interesting: still-life being not only the study of a particular subject, but a composition of objects, space and light.

Fortuitously, in the weeks since Olley died, the house has been photographed in detail, with plans under way to turn the high-resolution images into an interactive website.

It would be fitting, too, to preserve some of Olley's tableaus - the pomegranates in the jar, the yellow room and Chinese screen - and house them at another venue, gallery or museum. It could be done beautifully, with displays of her paintings and a corresponding re-creation of the place they were painted in.

But it would be extremely difficult and expensive to turn Olley's house into a museum with everything preserved intact. For reasons of security, entire sections would need to be roped off, so the visitor's experience would be one of peering into the gloom, rather than a meaningful engagement with the objects.

And unlike the Whiteley studio, the house is not of a scale that could accommodate dozens of visitors. Serious restoration work would be needed if it is to be turned into a public space.

And, when I visited on Friday, the house felt cold and dark without Olley's animating spirit. I saw her little bed, her brushes and the boards on which she mixed paint. But her paintings had been removed, and much of the contents looked like dusty junk. As she said, when the light wasn't good for painting, it was as if all the colour had been sucked from the room.

Philip Bacon says Olley had no pretensions about keeping the house and studio as a memorial to herself. This may be due to her modesty, and also her pragmatism. So much of her life was about supporting other artists, and enriching our culture with her gifts. Shouldn't this be her legacy too?

A few streets away in Paddington, at 45 Ormond St, is another artist's house that may be the best model for Olley's. It was the former home of composer Peggy Glanville-Hicks, and after she died in 1990 it was turned into a residence for composers to work. Glanville-Hicks believed composers needed "leisure and silence" for them to work creatively.

Let's see Olley's house turned into an artists' residence, where one or more artists can work for several months at a time. Parts of Olley's world - this little bohemia in gentrified Paddington - should of course be retained. But to turn the entire house into a museum would be more fitting for a Miss Havisham than the vital and generous person that Olley was.