Opera Australia chief Fiona Allan puts company on new track

Opera Australia’s new CEO, Fiona Allan, is planning property deals and investment in local stories and productions.

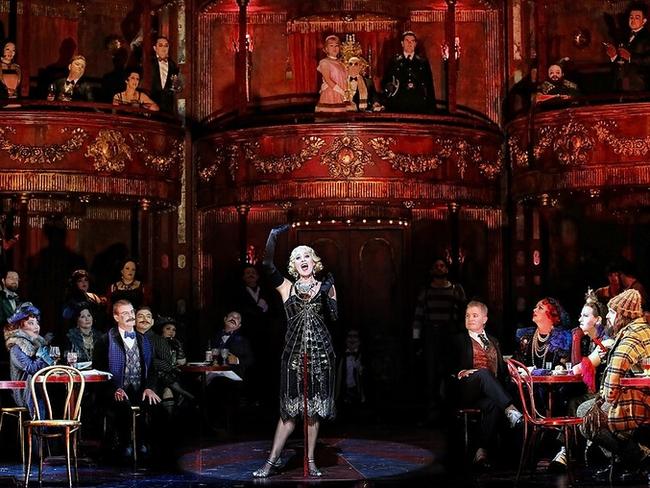

A new broom has swept into Opera Australia and the nation’s biggest performing arts company is poised to transform its approach to opera production, revenue and talent development.

Sydney-born Fiona Allan, who took up her post as chief executive of OA in November, says she wants to see the company be more substantially Australian and to offer career paths for professionals from across the performing arts.

The company is about to purchase property in regional NSW to build a production facility and warehouse, and it plans to move ahead with redeveloping its inner-Sydney headquarters, potentially releasing millions of dollars in asset value.

Allan is looking closely at OA’s business model and how the company will rebound from the pandemic, particularly the loss of revenue due to hundreds of cancelled performances and absent tourists. She says she is not considering redundancies.

A pandemic may not be the most propitious of times to take charge at a major opera company, but Allan seems undaunted. There have been “amazing” advance sales for some of OA’s headline productions this year, including The Phantom of the Opera and Lohengrin in Melbourne with tenor superstar Jonas Kaufmann.

Even so, the Omicron outbreak has kept people away from the Sydney summer season and threatens the best-laid plans.

“I think this year is going to be a tougher year for us than even previous years,” Allan says. “All of us had hoped that 2022 would be the recovery year and a new version of normal, and had programmed accordingly. We have a full program across cities, a national tour, schools tour – the full Opera Australia experience.

“The costs are sunk into that already because of the planning horizons that we have. And already, in Sydney summer, we are facing big box-office losses.”

Allan’s tenure at OA coincides with the arrival of Glyn Davis as chairman, after the departure this month of former chair David Mortimer. She says the pre-pandemic business model built up by artistic director Lyndon Terracini and her predecessor as CEO, Rory Jeffes – based on a high number of performances and turnover that reached $130m in 2019 – cannot continue with trading conditions as they are. It’s not only that OA can’t rely on audiences – and particularly tourists – returning in great numbers soon. Allan is clear that she wants to refashion the company’s operating model and to set the parameters of its artistic output.

“I have great admiration for Lyndon’s entrepreneurialism, his commerciality, the fact he has expanded the company, his eternal quest for excellence and exactitude,” she says.

“But I am interested in exploring some other things as well. I’d like to look at how do we put more of an Australian stamp on what is essentially a European art form, and what does having a national opera company mean in contemporary Australia.”

In contrast with Terracini’s co-productions with leading European opera houses and roster of international artists, Allan wants greater prominence given to Australian stories and creative talent.

She speaks of partnerships with tertiary institutions including the National Institute of Dramatic Art, and of closer involvement with the state opera companies. “I would like to see more Australian-created productions and not always a focus on the main stage – we can be putting opera in different places as well,” she says.

“We have some amazing talent development programs around young singers, but that could be extended to other states, it could be in partnership, we could be joining up a national infrastructure so that we see much clearer pipelines of talent.”

Asked whether her vision for the company falls within the purview of chief executive or artistic director, Allan says her role is to set OA’s overall strategy in consultation with the board. She won’t be drawn on Terracini’s term as artistic director, other than to confirm his current contract ends late next year.

Allan has returned to Australia after 18 years in the UK, where most recently she was both artistic director and chief executive of the 1850-seat Birmingham Hippodrome. She studied the clarinet, but knew from a young age that she wanted to be an arts manager; in fact, she wanted to run the Sydney Opera House. As a youngster she would be at the Opera House several times a month, sometimes slipping into performances without a ticket after interval.

“I had a clarinet teacher who played in the then Opera and Ballet Orchestra, who would sneak me into the pit,” she says. “I saw Dame Joan (Sutherland) in Dialogues of the Carmelites, from the pit.”

Allan says OA is considering two possible properties within striking distance of Sydney as the site for a new-build production centre. The company last year sold its Alexandria warehouse for $46m, following an earlier sale and leaseback of its Melbourne building.

The regional opera centre, which Allan would like open by 2024, will be the warehouse for sets and costumes, a training facility and possibly a venue for community outreach.

Allan is keen to progress with redevelopment of the Opera Centre in Sydney’s Surry Hills, in partnership with a property developer. OA would retain its offices and studios, while the airspace above could be developed as apartments. Allan says she is considering all possible revenue flows, from commercial musicals to investments.

Discussions about the company’s future model are under way with the board and with major government partner the Australia Council, and consultants will be coming to scope the business, she says. OA expects to report an operating deficit for 2021, but a smaller loss than was feared.

“We have nothing planned in terms of redundancies,” she says. “Over the Covid period we lost 25 per cent of staff across the board, every business area. We are not currently looking at redundancies.”

Since Allan arrived in November many have offered their two cents’ worth about the company’s future. Allan, who has 10 direct reports, says she has been struck by the size and complexity of a company with so many moving parts.

“I know all the component parts, but I’ve never worked to this scale,” she says. “It’s huge.”