Nicholas Harding’s sketches from the cancer frontline

Nicholas Harding has documented his recent treatment for cancer in sketches covering each day.

Before we turn to cancer, and one artist’s documentation of his treatment, let’s spend a moment on the theatre. Nicholas Harding calls himself a theatre tragic, which explains why he spends so much time inside rehearsal rooms around Sydney. In 2013 he went behind the scenes at the Sydney Theatre Company to sketch the creative team of Waiting for Godot, courtesy of his friend Hugo Weaving, who was playing Vladimir opposite Richard Roxburgh’s Estragon. Since then he has been back several times to the STC, and to Belvoir too, filling multiple notebooks with drawings that document the evolution of each production.

Harding loves the immediacy of theatre, the way the actors circle around on individual scenes trying to find the right note for any particular moment. “They’re sort of in a halfway place because they’re doing lines but they’re not putting everything into it yet,” he says. “It’s very much like how a painter works, where they deconstruct and put things together.”

His drawings are a fascinating insight into the theatrical process. They’re fascinating works of art, too, even if the artist thinks some are more successful than others.

“There might be nine pages of not quite getting there or not getting there at all,” he says, “and then I’ll hit the mark before building up for the next one.”

Harding has just finished sketching the rehearsals of The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, which opened at the STC on Monday, again with Weaving as the star, and Diplomacy, at the Ensemble Theatre, featuring John Bell and John Gaden, which opens tonight.

‘Some people sleep, some people read. I had lots of visitors, which takes your mind off things. I couldn’t read. Couldn’t focus. But when I could do something, I drew’

Harding won the 2001 Archibald Prize with a portrait of Bell, so working with the actor on Diplomacy was a return to familiar territory. But in a broader sense, his involvement with both plays marked a welcome return for the artist after a challenging few months in which he was diagnosed with cancer and then spent almost two months in treatment over Christmas.

Earlier last year, Art Gallery of NSW trustees had chosen Harding’s portrait of fellow artist John Olsen as an Archibald finalist. He had even appeared in a Foxtel Archibald documentary that followed a handful of artists preparing for the competition. But there he was, with barely any warning, facing long periods of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. It made sense, then, that he turned to art to understand this unfamiliar new world around him.

Just as he had done in the theatre, Harding used his talent to capture fleeting moments behind the scenes. Even when his strength started to fade and his concentration fell away, Harding continued to work, recording every step. All these drawings are contained in two notebooks, their pages full of the highs and lows of treatment, from flowers and snacks to visitors and medical equipment and pills.

“It’s second nature,” he says. “I’ve been doing it for decades. It’s something that’s just compulsive.”

There are no rules that control how patients confront cancer, and everyone deals with treatment in their own way. “Some people sleep, some people read. I had lots of visitors, which takes your mind off things.” Drawing for him was inevitable. “I couldn’t read. Couldn’t focus. But when I could do something, I drew.”

His first notebook opens with a drawing of the outside world and handwriting at the top: Lifehouse day 1 Newtown. The date is November 11, 2017. Harding was in a room at Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, the renowned cancer treatment centre in Sydney, looking out through vines growing over the window as he prepared for his first day of treatment.

One of the first things the doctors had told him was that he would never be the same again. Harding recalls that as unsettling advice. “You try to process it,” he says, “but you can’t, because what does that mean?” Harding was in good hands at the Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, where the details of treatment were explained to him, along with the side effects he was likely to experience.

The artist was eager to face his predicament head-on. Equally, he wanted doctors to be as direct as possible, to tell him “how it’s going to be”. Art, then, was an important way for him to stay sane and to stay connected to “my old self”.

“This keeps you in touch with how you were, and the part of you that you hope to remain.”

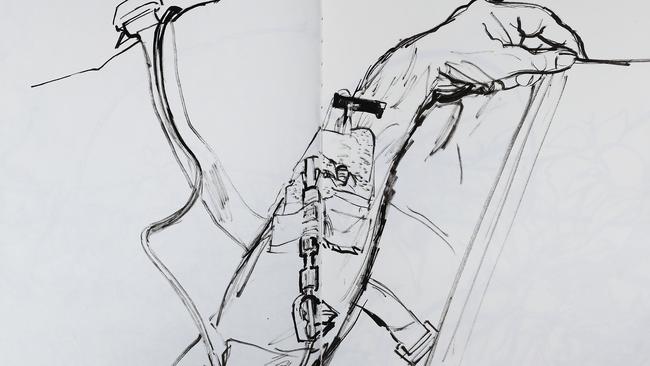

He made a sketch for each day of treatment, at least for a while. He drew some of his many visitors, as well as the gifts they brought along: flowers, food, ice cream, even a homemade chocolate smoothie that Weaving brought one day. He recorded other patients, a feeding tube, some pills and the various stages he encountered along the medical journey, including a cannula that had been inserted into his arm.

There are also several self-portraits. In one of them, he’s sitting on his couch at home, drawing orchids and OxyContin and a Picasso etching of a naked woman. This was a reference to his particular circumstances: Harding had cancer at the base of his tongue, having contracted human papillomavirus, or HPV, a common virus that can be transmitted through oral sex. (Australia was the first country to introduce a free national vaccination program against HPV, starting with girls in 2007 and boys in 2013.)

On another page he drew a self-portrait opposite a drawing of the Hill End painter Luke Sciberras, who had sent a message from Katoomba Hospital, where he was having a heart check-up. Both artists are shown with tubes attached to their bodies, and this is what Harding has written under his own portrait: “My tube is bigger than your tube.”

For all these drawings Harding uses a pen — specifically a Schmincke Aero Color Liner No 3, the same one he uses for theatre rehearsals. Unlike pencils, the pen means his lines cannot be easily erased. “That’s one of the disciplines of it,” he says. “You’ve kind of got to visualise what you’re looking at and how you’re going to transpose it, and that takes a bit longer. That’s one of the beauties of both this and rehearsals. It’s not one moment, it’s a short period of time, and that might take about five minutes.”

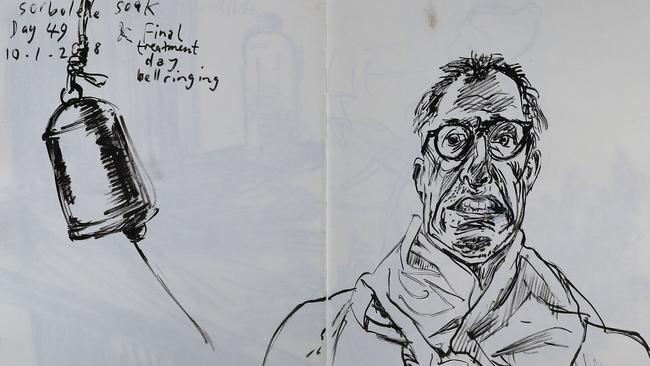

Towards the end of his treatment, the frequency of Harding’s drawings dropped away. He had been warned about this period. His energy levels waned, water started to taste like metal and he generally felt lethargic, like he was jet-lagged. He was no longer doing a drawing every day, but he still came close. Then, on day 49, his final picture shows him ringing a bell to celebrate the final day of treatment.

That was January 10. Harding had completed seven weeks of chemotherapy and 35 sessions of radiation therapy. Then came two tough weeks at home when he could barely stay awake. He has since returned to work, albeit at a reduced rate, and will learn the results of his treatment next month. And yes, he plans to document that stage as well.

Harding has posted some of these drawings on Instagram but otherwise has kept them close to home. They’re not being prepared for an exhibition, at least not yet.

All this activity, though, has given him an idea. It relates to his recent painting of the Flinders Ranges — Wilpena eucalypt and wattle, a finalist in last year’s Wynne Prize — that hangs in his living room in Sydney. He returned to South Australia last August to gather more material, only to find that fire had torn through the area, leaving the vegetation black and charred, no longer full of colour and life.

It was around this time that he felt a lump in his neck. “I want to do a big painting of that size,” he says, pointing to the picture in his living room. “A fire cycle. That will be my major statement of what I’ve been through. For me it’s become an allegory for what they did to my throat, which is to burn the f..k out of it ... The green shoots beginning to appear from the blackened scrub (will be) a signifier of future recovery. ”

But when it comes to the drawings, he has no firm plans. Friends have encouraged him to enter a self-portrait into the Archibald Prize, but he’s not sure he would have anything ready in time, since entries need to be submitted by mid-April. If not the Archibald, then, what will he do with all these drawings? It’s too soon to say.

“I don’t know how it’s going to pan out at this stage,” he says. “It’s a lot to process and it’s only two months since treatment finished. It all happens very quickly. This is one of my ways of processing.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout