National Indigenous Art Triennial opens in Canberra

Curator Hetti Perkins invited artists to think about ceremony in myriad forms, from painting to sculpture, protest and performance.

Canberra may be the perfect place in which to hold an exhibition called Ceremony. No other Australian city is laid out with Canberra’s formal design and symbolism – from the axis linking the Australian War Memorial and Parliament House, to the cultural institutions along the shore of Lake Burley Griffin.

It is also, of course, a place of significance for the region’s Ngambri and Ngunnawal peoples, and for Australia’s Indigenous population generally. The High Court was where the falsehood of terra nullius was overturned in the 1992 Mabo decision. The Aboriginal Tent Embassy, first raised in 1972, has maintained a visible presence of Indigenous Australia at the seat of federal power.

Much earlier, as art curator Hetti Perkins explains, the Indigenous people of Canberra – the anglicised name for the national capital is derived from Ngambri – had a ceremonial ground near the current site of the National Museum of Australia. The historic meeting-place eventually was submerged after the damming of the Molonglo River in 1963 to form Lake Burley Griffin. As Perkins puts it, the “whitefella sacred geometry” of Walter Burley Griffin’s Parliamentary Triangle and lake has been imposed over the sacred ground of the Ngambri.

Perkins is the curator of the 4th National Indigenous Art Triennial at the National Gallery of Australia, to which she has given the title Ceremony. It’s about ceremony in many forms, from the ancestor stories, belief systems and languages of First Nations peoples, to contemporary expressions of Indigeneity through performance, mark-making, artistic practice and protest. It opens at the NGA on Saturday.

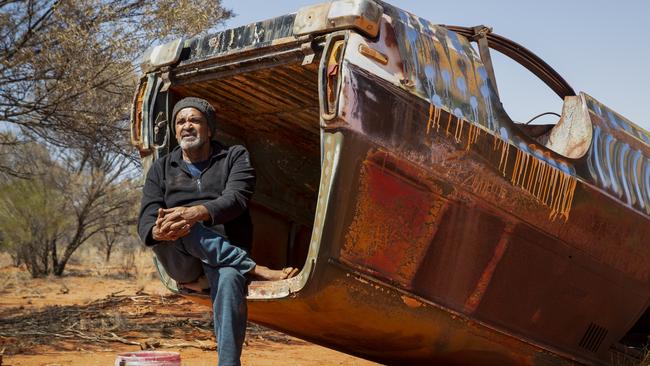

One of the most striking installations, by Robert Fielding, is of an abandoned car brought to Canberra from his country, near Mimili community, SA. In the piece called Holden On, the wrecked Holden has been painted with culturally significant designs, fitted with lights, and then installed on a pontoon so that it appears to float on Lake Burley Griffin. Perkins says Fielding’s work is layered with symbolism: of the vehicles that carry the stories and memories of people living in remote communities, and its position on Lake Burley Griffin being a reminder of the “annexing” of Ngunnawal and Ngambri country to make the modern federal capital.

“Those cars have their own stories – the people who owned them, the places they went, and the service they provided,” Perkins says. “But then, having it positioned on the lake, it’s making a point about the lake and being flooded. People may think, ‘That’s a bit surreal, there’s a car on the lake’. But it’s actually the lake that’s surreal, an instant lake.”

The Triennial was to have opened last year but has been delayed because of the pandemic. The exhibition includes work by 19 individuals and groups of artists, whose contributions include dance, carving, painting, ceramics, photography, ceremonial shields, weaving, video and installation, all connected by the idea of ceremony.

Perkins did not set out to define what a ceremony is, but says it can take various forms. Some common characteristics are repeated action, involving people alone or in groups, and a sense of occasion, whether joyous or solemn. Often there are rules about form and an expectation of appropriate behaviour.

“It’s about people coming together in a choreographed way for a common outcome,” Perkins says. “What I love about the idea of ceremony is that we acknowledge country wherever we go – it’s a small ceremonial act that people do individually, blackfellas and whitefellas. The idea of ceremony is very prevalent, around us and in us.”

Perkins’s exhibition includes a major new commission from Pintupi artist Mantua Nangala, marking 50 years of Papunya Tula Artists. Her large-scale triptych in fine-dotting technique depicts the sand dunes of her desert country around Kiwirrkura, WA, and – although the secret details are not revealed – alludes to the journey of the ancestral Kanaputa women through the women’s sites of Mukula, Marrapinti and Yunala.

Other works in the exhibition have a strong performative element. Language is present in the work of several artists, such as video artist Gutingarra Yunupingu who uses Yolgnu sign language and the “possibilities of non-verbal communication in examining and representing self and culture”.

Robert Andrew has made an electromechanical “writing machine” that works on a large surface prepared as a palimpsest. The mechanical scribe etches away at the white surface to reveal ochre underneath, spelling out a phrase of cultural significance for Canberra’s Ngambri and Ngunnawal people.

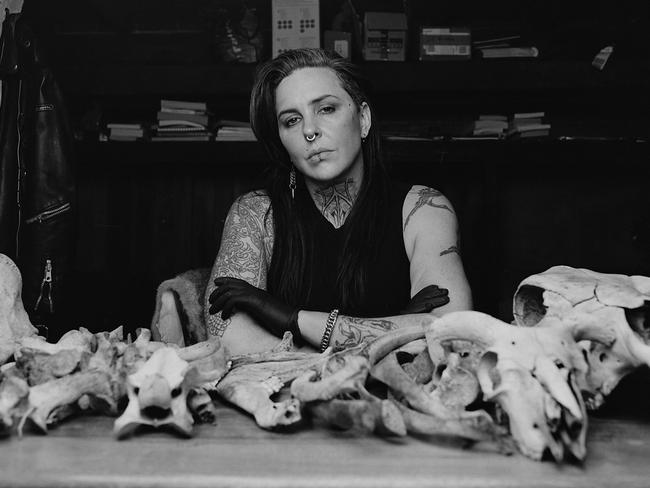

Language is also central to SJ Norman’s work called Bone Library, in which he will carve words from Indigenous languages onto bleached sheep and cattle bones – thus making a connection, says an essay about the exhibition, between “settler-colonial pastoralism, displacement of First Nations from their land and the loss of Indigenous language through this process”.

The 50th anniversary of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy is commemorated with a soft sculpture, Blak Parliament House, by Yarrenyty Arltere and Tangentyere artists, led by Marlene Rubuntja. The soft sculptures, representing new Parliament House, a gorgeous coat of arms, as well as human figures, animals and mythical creatures are made from reclaimed blankets that have been dyed with local pigments, tea and other materials. In a statement, Rabuntja says: “This Parliament House is for everyone. White, Aboriginal and any other colour. It belongs to the community.”

Asked about the recent anniversary of the Tent Embassy which was overshadowed by the arson attack on Old Parliament House – an act condemned by the Tent Embassy organisers – Perkins says she prefers to focus on the achievements of the Tent Embassy for Indigenous recognition.

“What the Tent Embassy is really about is land rights – and land rights is fundamentally about caring for country,” she says. “So that’s the important message that I think people should be taking from this 50th anniversary, and looking at the achievements.”

Perkins has a lifelong association with Aboriginal rights and the protest movement. Her father, Charles Perkins, was an organiser of the 1965 Freedom Ride that challenged racial segregation in northwest NSW, and a prominent figure in Aboriginal politics and the public service. In the 1970s when Perkins was working at the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, later rising to departmental secretary, the family lived in Canberra.

Another family, the Houses, lived not far away and also were involved in the protest movement. Perkins has invited Matilda House and her son Paul Girrawah House to participate in the exhibition as custodians of Ngambri-Ngunnawal country. Paul has taken up the practice of tree-carving, incising several eucalypts around the gallery with ceremonial designs. Perkins says she hopes he will be able to continue the traditional practice throughout the Parliamentary precinct.

The Triennial was first held in 2007 and was the first large-scale curated exhibition dedicated to contemporary Indigenous art and artists. Perkins says the Triennial is not a survey or representative of artists around the country, but instead is a curated exhibition in which she discussed and planned the commissions with the selected artists.

“I wanted to offer a space for artists to talk about how ceremony is very much part of their experience, their process and their lives, no matter where they’re from,” she says.

“It’s amazing how artists have responded in these myriad ways and with such enthusiasm and generosity.”

The 4th National Indigenous Art Triennial: Ceremony is at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, March 26-July 31; UQ Art Museum, Brisbane, August 19-November 26; and Shepparton Art Museum, Victoria, December 18-February 26, 2023.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout