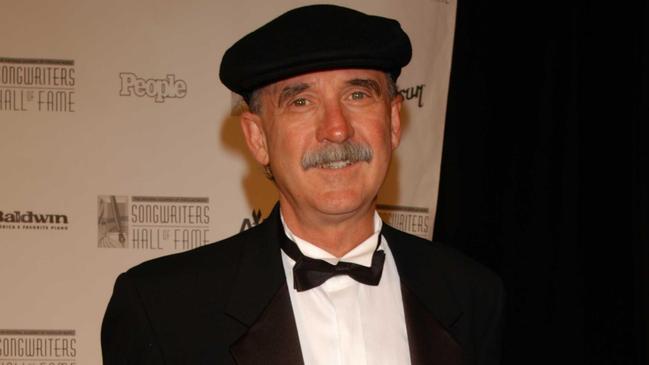

Will Jennings wrote the words that made the whole world sing

Celine Dion didn’t like Will Jennings’ My Heart Will Go On when she first heard it, but her husband convinced her it was at least worth a demo.

OBITUARY

When it came to writing a song, Will Jennings leant on the Cheshire cat’s advice to Alice in Wonderland that if you don’t know where you are going, any road will take you there.

Jennings wrote some of the most striking songs of the last 50 years – regularly for films, knowing little, sometimes nothing, about them.

His inspiration came from within; he could sense in the sometimes sparse musical works in progress with which he was presented a slice of humanity as deftly as Hal David did when he imposed lyrics on the sure-footed gems sent his way by Burt Bacharach.

A perfect example of Jennings’s artistry was a song he wrote that the filmmaker did not want, for a movie Jennings had not seen, built on the vaguest outline of its plot – an old woman looks back on a moment of risky love that ended in tragedy more than 75 years before.

Director James Cameron had decided that composer James Horner’s orchestral soundtrack to Titanic would extend to encompass the film’s end credits. He was adamant it should not be a pop song.

It had been put to Cameron that perhaps an anthem such as Whitney Houston’s soaring interpretation of Dolly Parton’s I Will Always Love You from the 1992 film The Bodyguard would do the trick. Cameron loved that song, but thought it a fluke. Where would they get another like it?

Still, Horner preferred the song option. He’d seen a rough cut of the movie and remembered going home deeply impressed and writing half a dozen themes that night, which grew to become the soundtrack. He worked one of them into an eight-minute sequence that would play out as the credits rolled.

But Horner had always seen it as his job to keep the audience in the cinema: “It’s my personal belief I should never let anyone put their coats on (before the credits end).”

Horner had worked once with Jennings who, despite his low profile, already had several Grammys (co-writing Tears in Heaven) and an Academy Award (co-writing Up Where We Belong), and invited him around to be secretly briefed on a song for Titanic.

Two years earlier, Jennings had met a centenarian whose vitality had impressed him. She was “about 101 years old when I met her … I realised she could have been on the Titanic”. With her in mind, and Horner’s slender version of the storyline, he worked for three weeks on the lyrics.

They are simple, conversational almost:

Love can touch us one time

And last for a lifetime

And never let go ’til we’re gone

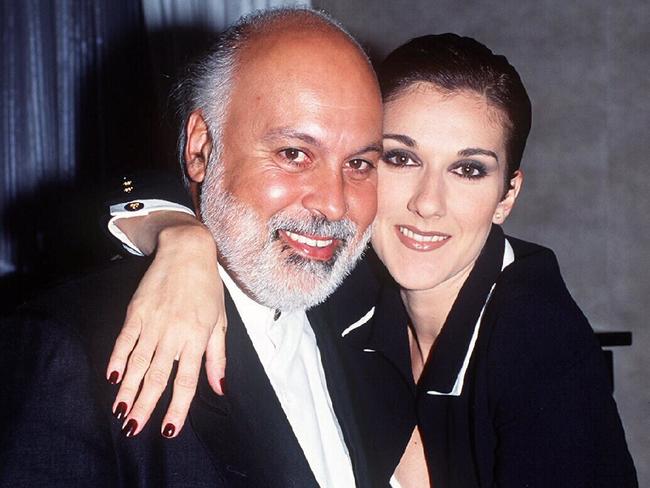

Horner loved them. Days later at a Las Vegas hotel, Horner, on a dodgy piano and in his schoolboy voice, sang the first rendition of My Heart Will Go On to Celine Dion. She had doubts.

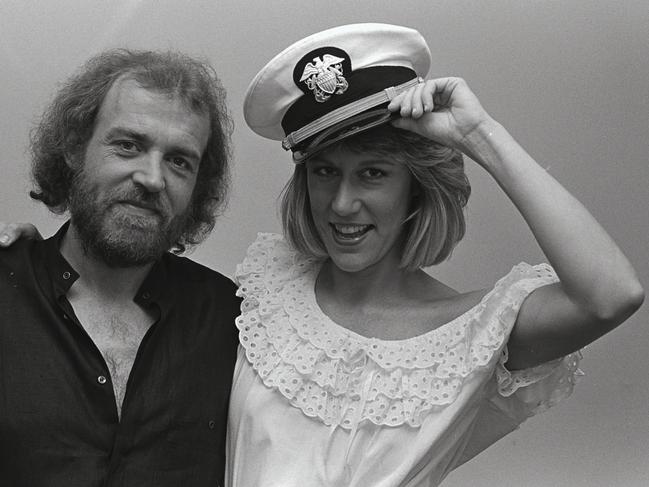

“I didn’t really like the song at first,” Dion told Jonathan Ross. “Thank God they didn’t listen to me.” Her husband, René Angélil, thought it was worth at least recording a demo.

Cameron is a grumpy perfectionist who always wants his way. Horner kept the tape in his pocket until he thought it the right moment, asking the director one morning “Are you in a good mood?”.

Cameron listened and was overwhelmed. He left the room in tears. He had his Bodyguard moment.

The Titanic soundtrack broke the records that film had set five years earlier: it topped the Billboard charts for 16 weeks, sold 30 million copies and remains the biggest-selling, mostly orchestral soundtrack of all time. The Dion single sold 18 million copies – the second-biggest-selling single by a woman ever – was No.1 in 25 countries and won an Academy Award and four Grammys.

But it is short of the best song Jennings ever wrote. Of all the great lyricists – David, Paul McCartney, John Lennon, Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, John Fogerty, Billy Joel, Bernie Taupin, Jimmy Webb, Stevie Wonder – perhaps only McCartney has come near to crossing so much musical territory and scoring hits in unlikely settings.

The least likely setting for Jennings was his Texas birthplace amid the oilfields where his father laboured. At school he liked English and poetry, and studied them at several Texas universities, securing a master’s in English in 1967, and then teaching while playing in a local band and hoping to make it as a country songwriter.

Newly married, he moved to Nashville and was quickly successful, providing the successful duo of Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynne with Feelins, a country chart-topper for two artists themselves legendary songwriters. With that under his belt he moved to Los Angeles in the hope of writing songs for films and, by all accounts, he was undaunted by the talent pool living off Hollywood.

He scored a track on a forgotten Walter Matthau film called Casey’s Shadow. The song was recorded by Dobie Gray, but also forgotten. It didn’t matter. By then Jennings was moving in elite circles and his talent was noticed.

BB King was in a rare fallow period and looking for songs to restart his career. At that stage, Joe Sample, a pioneer of the electric piano sound, and his band, the Crusaders, had worked with Jennings and they were employed to write the next two albums for King.

In the meantime Jennings co-wrote a song for Dionne Warwick, I’ll Never Love This Way Again, a million-seller that broke her five-year hit drought.

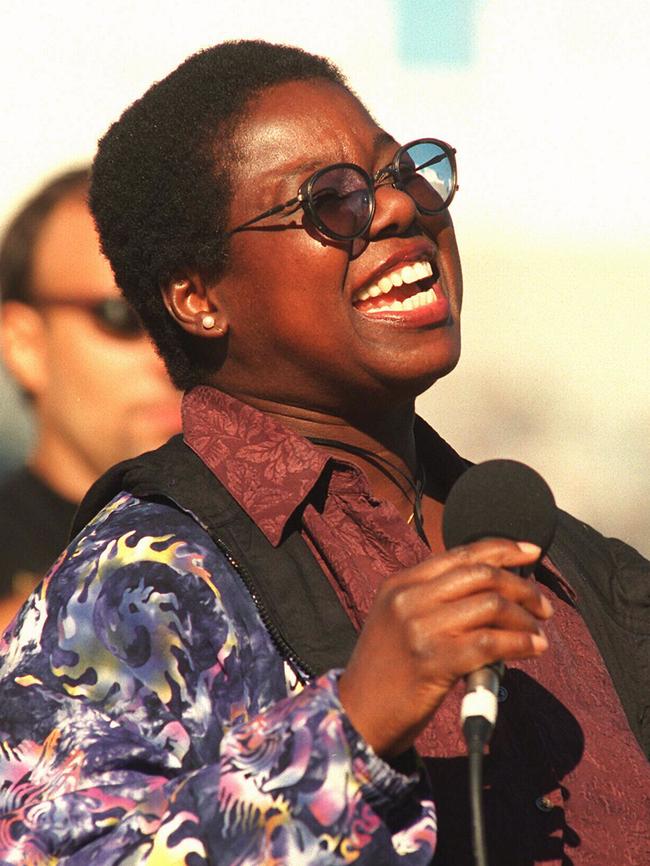

The Crusaders had been hot in the early ’60s and batted on but recently had been a backing band for others including Steely Dan, Marvin Gaye and Joni Mitchell. Jennings fixed that by writing Street Life with Sample, who called in singer Randy Crawford to sing it.

The jazz funk masterpiece became Crawford’s first and the Crusaders’ only hit.

Jennings’ purple patch had begun. Sample and Jennings then wrote One Day I’ll Fly Away for Crawford, a break-up song in the mould of I Will Survive, but with a soulful sophistication seldom found in popular music.

Why live life from dream to dream?

And dread the day that dreaming ends?

Crawford’s immaculate phrasing would have put a smile on Sinatra’s face. She had too much respect for Jennings’s words to employ the graceless bombast of the ’80s power ballads.

In 1980 I heard a BBC announcer say after playing it: “We’ll be listening to that song 25 years from now.” And Sample is posthumously forgiven for nicking the melody from Tchaikovsky’s Waltz of the Flowers.

The song, performed by Nicole Kidman, would be part of Baz Lurhmann’s Grammy-nominated soundtrack for Moulin Rouge that topped Australian charts for 11 weeks and was the best-selling album of 2001.

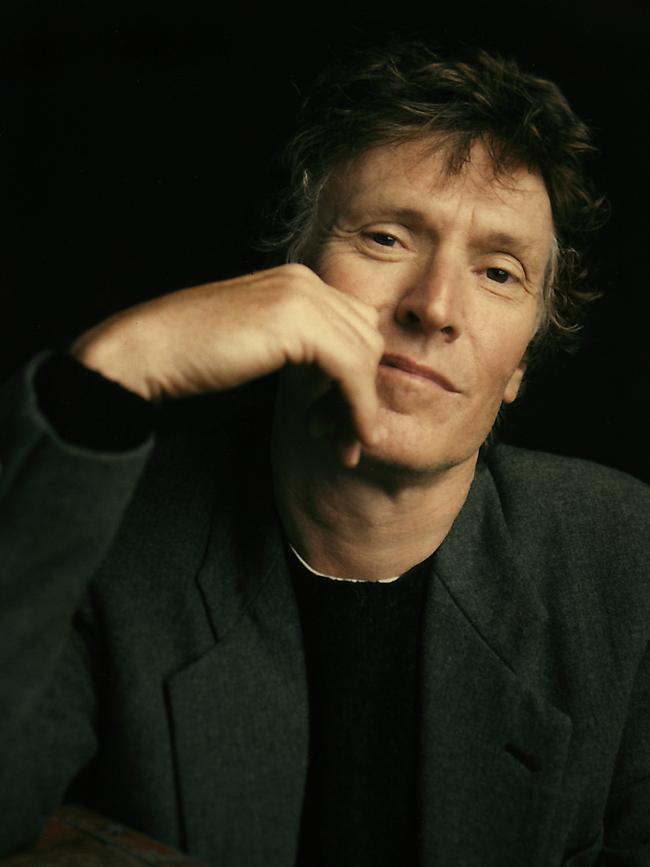

By 1980, former Traffic and Blind Faith singer and multi-instrumentalist Steve Winwood was lost. He’d been in two of the first supergroups and written some of their best songs, but the spark was gone.

Winwood asked Jennings to help write songs for a new album. Winwood would do literally everything else, other than the cover artwork. The first song set the scene:

When some cold tomorrow finds you

When some sad old dream reminds you

How the endless road unwinds you

While You See a Chance was Winwood’s last roll of the dice, its lyrics entrusted to Jennings. “We didn’t talk about what the song was about,” Winwood told Rolling Stone that year. “He just came up with this lyric, and it was right for me, right for him and right for the song.” And right for charts the world over.

Jennings would write songs for the next two Winwood albums, including Valerie, The Finer Things, Back In The High Life Again and Grammy award-winning Billboard No.1 hit Higher Love.

In 1983, husband-and-wife team Jack Nitzsche and Buffy Saint-Marie had written some music for the film An Officer and a Gentleman. The film’s producer, Taylor Hackford, was just about finished when he had a change of mind and called for a song to run over its end credits.

He wanted a duet, but not with Jennifer Warnes. Then Warnes suggested she sing it with Joe Cocker and Hackford came around. Cocker was on tour and playing in Seattle. One afternoon in late 1982 he flew to Los Angeles, meeting Warnes for the first time in the studio, returning for that night’s show as soon as his vocals were complete.

It was only Cocker’s second Billboard No.1 song, the first having been his gospel-rock reworking of The Beatles’ A Little Help From My Friends 13 years earlier. Up Where We Belong dislodged Men at Work’s Who Can It Be Now? to take top slot on November 6, 1982. The song won another Academy Award and a Grammy, seeing off nominees McCartney and Wonder. It is also listed by the Recording Industry Association of America as one of the Songs of the Century.

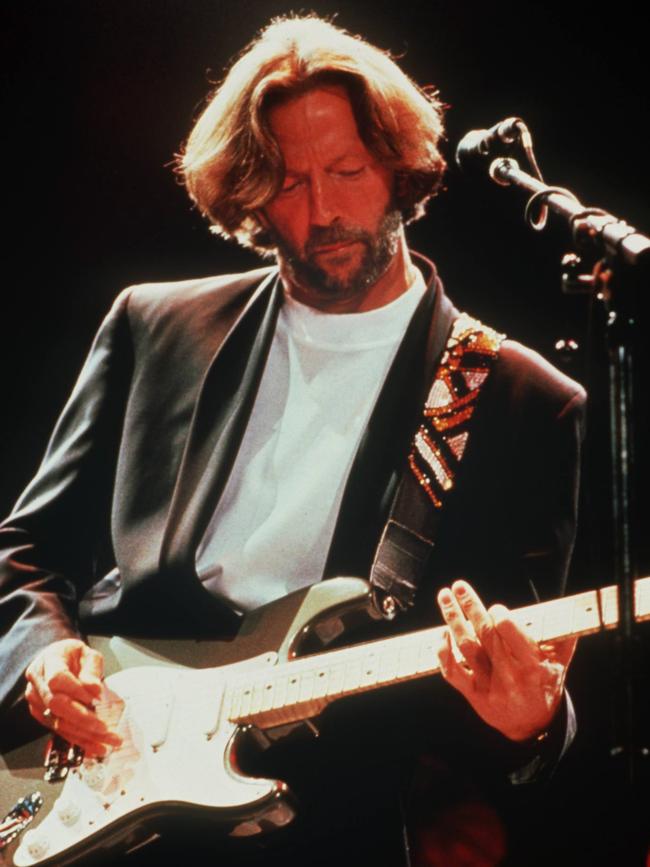

Jennings had a last No.1 in him, and it came about in an odd way. Through Winwood, Jennings had met Eric Clapton, who late in 1991 called him to help finish a song on which he was stalled but that was important to him. In March 1991, Clapton’s son Conor, four, had died falling from an apartment window 57 floors above Manhattan. Clapton had a song title – Tears In Heaven – and the first verse complete but nothing else would come.

Jennings encouraged Clapton to keep going. It was so private a thing he felt he was intruding, but Clapton insisted and Jennings wrote the rest, including the words of which he was most proud:

Time can bring you down

Time can bend your knees

Time can break your heart

Have you begging please

Tears In Heaven rose to the top of charts around the world (but only managed No.37 in Australia) and won three Grammys, including Record of the Year and Song of the Year. On January 16, 1992, Clapton recorded it before a small audience in England as part of his Unplugged album, helping it also top charts worldwide, this time including Australia.

Had Jennings a sense it was a hit? In an interview with the Songfacts website he said it “was furthest from my mind”. “I was so involved in the sensitivity of the subject, and I didn’t even think about that. I’m passionate about all the songs I write, but it was just in another place entirely, another category.”

He also wrote albums of songs for Roy Orbison and Barry Manilow, country superstars Rodney Crowell and Tim McGraw, and a few for Jimmy Buffett, co-writing perhaps his most touching song, Beyond The End.

On receiving the Academy Award for Up Where We Belong in 1983, he thanked “Tyler”, the small Texas town where he grew up and long ago returned to live in modest anonymity.

In 2015, Rolling Stone listed its greatest 100 songwriters. Jennings did not make the cut.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout