Why songs of the 1970s mean so much to boomers

Before the walkman and streaming, listening to the music of great artists was a shared experience.

Music can be a sort of time machine. When I hear The Carpenters’ version of (They Long to Be) Close to You, I am transported back to the family television room of my youth. I can still picture Karen Carpenter on the black and white screen, seated behind her drum kit, gently biting her lower lip between opening stanzas.

Similarly, any track from the album Deep Purple in Rock reminds me of teenage parties. Cat Stevens’ Tea for the Tillerman will forever summon forth memories of the girlfriend who ran away from her alcoholic mother. This LP was one of her few possessions, and she played it incessantly in her one-room bedsit.

I didn’t own copies of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s Déjà Vu, or Carole King’s Tapestry, but they were everywhere at the time, and so I remain conversant with every note and lyric.

There were also live performances in my youth that still elicit vivid memories, Frank Zappa’s first tour of Australia being one example. It was 1973, and Sydney was experiencing power blackouts due to industrial action. To my great relief, and no doubt Zappa’s, the Hordern Pavilion had its own generator. The crack band, including jazzers George Duke and Jean-Luc Ponty, was road-testing the material which would later appear on the album Apostrophe (’).

I also have vivid memories of Pink Floyd’s 1971 tour down under, where they were forced to play on a makeshift stage at Randwick Racecourse with a gale-force wind nearly blowing them onto the racetrack. Mind you, the weather added a certain frisson when Roger Waters let out his evocative scream during Careful with That Axe, Eugene. The sound quality was awful, and the show began hours after it was scheduled, but all that frustration only adds to my recollections.

University days also provided a string of memorable experiences thanks to the lunchtime concerts staged by the student union. Lodged in my memory is Australia’s answer to progressive rock, MacKenzie Theory, with Cleis Pearce whipping up a storm on her electric viola.

Scabrous outfit The 69ers also left an indelible impression, especially their scatological tune Bum Sweat, Crusty Bits and Stangers.

Music has a remarkable capacity to occupy our brains, attaching itself to specific times and places. As neuroscientists such as Daniel J. Levitin have shown, our physiological response to music is highly complex, engaging many different parts of the brain simultaneously.

Multiple-trace memory modelling suggests that specific memories are cross-coded with the context in which they were formed, and there’s nothing quite like music to prompt those unique memory cues with their time-specific setting. While repeated listening to old favourites diminishes their capacity to invoke memories, when we hear a song that we haven’t listened to for a long time the floodgates are often opened, triggering deep emotions and recollections.

Researchers have also noted that we tend to respond best to music that we denote “our music”, which inevitably means the music of our teens and twenties – the age at which we listen to music to make sense of the world. So deep are these memories that even brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s cannot expunge them. Indeed, people suffering advanced types of dementia may no longer be able to identify family members but play them a song from their youth and they will frequently sing along, word perfect.

Why do we keep returning to the music of our youth? Studies confirm that our musical tastes are largely locked in by the time we hit our twenties. There is also plenty of research to show that most of us stop seeking out new music around the age of 30. For the rest of our lives, we tend to reach for the music of our youth. One study found that our favourite songs activate the pleasure areas of our brain, releasing dopamine, serotonin and oxytocin. The more we like a song, the more intense those neurotransmitters become. What’s more, with familiar songs, our brains anticipate the high points of the tune, triggering even more positive brain chemicals.

The way we respond to music is also culturally ordained: it’s not inherent in the music itself. While it’s long been assumed that minor chords are more likely to evoke melancholy feelings while major scales are considered to be happy, that simply doesn’t hold true for people with only sporadic exposure to western music.

In one study, remote communities in Papua New Guinea were compared with musicians based in Sydney to gauge their separate reactions to specific chord progressions and melodies. The PNG folk were just as likely to choose a minor scale as being happy as they were a major scale. Our responses to music are reinforced by the cultural use of specific music, say to accompany events such as parties, funerals or weddings. Having learnt how to respond to types of music, we can thereafter use music to help regulate our moods.

In the 1960s and ’70s, music was stuff to be shared. I loaned my King Crimson and Gentle Giant albums to my high school English teacher, and he responded with his Little Feat and Steely Dan discs. My friends and I would regularly gather in front of a stereo system for the sole purpose of listening to an album together.

Music back then had social consequences. To simply walk down the street with certain LPs under one’s wing (front cover always facing out) was to make a public statement about who you were.

When cassette tapes arrived, we created compilations of favourite tracks and handed them to our paramours, thus providing a tangible demonstration of the sort of person they were getting involved with.

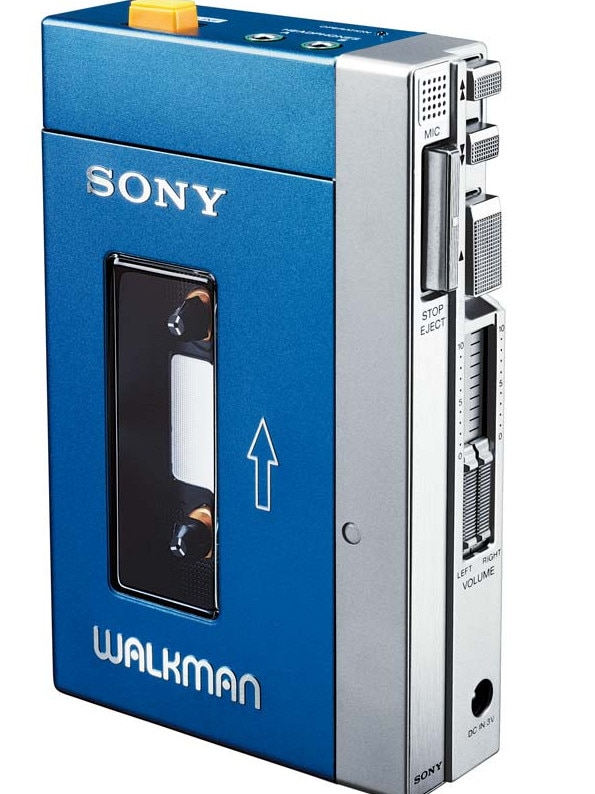

But in the late 70s came the Sony Walkman. Suddenly music was no longer something to be shared. The very nature of music changed. Music became increasingly personalised, piped through a headset and excluding other people from the listening experience.

Today, apart from live settings, music is mostly consumed in private and rarely shared with others. I doubt that many young people gather to simply sit still and listen to an album. Thanks to streaming services, music can be turned on and off like a tap. The listener has far less investment in the music than they did when they had to travel to a store and hand over hard-earned cash.

Some 10 million songs are uploaded to streaming services every year. As often as not, the music we hear is being determined by algorithms. Even the pleasure of following band members from album to album has vanished. Only the title artist now gets a credit on the streaming service, and supporting musicians are summarily ignored.

Music today is so accessible and absurdly abundant that I fear it is losing its value. From observing young folk today, music appears to be something that accompanies screen games, or is played in the background while doing other things like homework.

Of course, every generation believes the music of their formative years to be the best ever created. That’s because it is often embedded in our brains alongside intense and emotional memories. But I do wonder whether music will have the same resonating impact on today’s youth that we boomers enjoyed in our formative years.

Tony Wellington is the author of Vinyl Dreams: How the 1970s Changed Music (Monash University Publishing, $36.99).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout