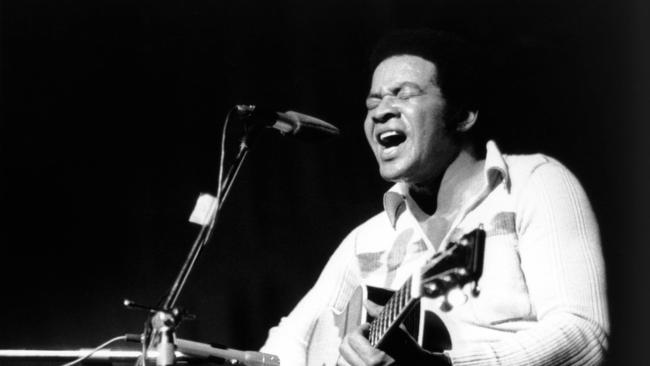

The sound of beauty and soul: remembering Bill Withers

Bill Withers avoided the spotlight in later years, but his presence lived on through his ubiquitous songs.

OBITUARY.

Bill Withers. Musician. Born July 4, 1938. Died March 30, aged 81

Bill Withers grew tired of people telling him “We thought you were dead”, but as the superstar who walked away at the height of his success and opted for a 35-year self-imposed silence, it was an easy mistake to make. “Sometimes I wake up and I wonder myself,” he joked.

After a stream of memorable hits in the 1970s that stand among the best-loved in the canon of popular music, he stopped making records and performing in 1985. There were no comebacks and no desire to put himself back in the spotlight. Even when a tribute concert was arranged in his honour at Carnegie Hall in 2015, he declined to sing with Ed Sheeran and the other stars who had gathered to pay homage.

Yet his presence lives on through his ubiquitous songs — and from Ain’t No Sunshine and Lean On Me to Lovely Day and Use Me, what songs they were. Sting, one of the countless artists who covered Ain’t No Sunshine, cogently summed up the appeal: “The hardest thing in songwriting is to be simple and yet profound,” he said. “And Bill seemed to understand, intrinsically and instinctively, how to do that.”

In his brief career Withers’ songs won him three Grammy awards and four further nominations. Barbara Streisand, Michael Jackson, Liza Minnelli, Aretha Franklin, Tom Jones, Paul McCartney, Mick Jagger and Diana Ross were among those who covered his work.

His music was also sampled by hip-hop artists including Jay-Z, Kanye West and Tupac Shakur and featured in countless Hollywood films and TV commercials. No karaoke session or TV talent show seemed complete without someone singing one of Withers’ hits and his songs were used in the official inauguration celebrations for at least two American presidents.

All that was missing from the on-going celebration of his music was Withers himself as he hid away in the luxury home his royalties bought him high in the hills above West Hollywood.

There were occasional sightings, such as his induction by Stevie Wonder in 2015 into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and he seemed grateful enough for the recognition. “I see it as an award of attrition,” he said. “What few songs I wrote during my brief career, there ain’t a genre that somebody didn’t record them in. I’m not a virtuoso, but I was able to write songs that people could identify with. I don’t think I’ve done bad for a guy from Slab Fork, West Virginia.”

Yet he had been away so long that mostly when he ventured out, nobody recognised him. In a rare interview around the time of his induction, he told a story about having lunch in a restaurant one Sunday and overhearing a group of women in the next booth mention his name.

“They were talking about this Bill Withers song they sang in church that morning,” he said. “I got up on my elbow, leaned into their booth and said, ‘Ladies, it’s odd you should mention that because I’m Bill Withers’.”

Needless to say, nobody believed him.

His early retirement and enigmatic life were examined in the 2009 film documentary Still Bill. It portrayed a man who had never had second thoughts about walking away, although there were enigmatic moments that suggested something darker was in play. At one point he played a few chords on the piano and announced to the camera: “Thoreau said most men live lives of quiet desperation. I would like to know how it feels for my desperation to get louder.”

He is survived by his second wife, Marcia (nee Johnson) whom he married in 1976. She directed his lucrative publishing company, licensing his work from an office on Sunset Boulevard. His children, Todd and Kori, also worked for his management company. A previous marriage to the actress Denise Nicholas, the star of the American TV sit-com Room 222 ended in divorce after less than a year.

William Harrison Withers Jr was born on American Independence Day in 1938. The youngest of six children to Bill, a coal miner and Mattie (née Galloway) who remembered a grandmother who had been born into slavery, he grew up in rural poverty, made worse when his father died when he was 13. Asthma and a stutter led to him being designated as “handicapped” at school and his main pleasure came from singing in church.

Desperate not to follow his father down the mine and even keener to escape the Jim Crow laws that systemised racial segregation across the South, at 18 he enlisted as a non-conscript in the US Navy, which was theoretically non-segregated. He was disappointed to find out that the practice was somewhat different, but he served for nine years.

He moved to Los Angeles, where he took a job with the Douglas Corporation, installing lavatories in aircraft. Although he had sung with bar bands in his navy days and knew he had a good voice, he had no thoughts of turning professional until he attended a Lou Rawls show.

“I was making $3 an hour, looking for friendly women, but nobody found me interesting. Then Rawls walked in, and all these women are talking to him,” he remembered. “He was being paid $2,000 dollars a night and he didn’t even have to get out of bed in the morning.”

At the time he had never played a guitar, but he bought a cheap model from a pawn shop, taught himself a few chords and began writing songs between factory shifts.

Saving from his weekly paycheque until he had enough to record a rudimentary demo, he hawked his songs around the Los Angeles record companies but found no takers until he met Clarence Avant, a black music executive who had just started an independent label called Sussex.

Avant recruited Booker T Jones of Booker T and the MGs fame to produce Just As I Am his 1971 debut album. “He came right from the factory and showed up in his old clunk of a car with a notebook full of songs,” Jones recalled. The album was recorded in three four-hour sessions and the record’s cover photo was taken during his lunch break at the factory.

By the time the album was released Withers was 33. It was an extraordinarily late age to be launching a recording career but Just As I Am made an immediate impact. Singing in an understated, conversational style with sparse arrangements, covers of Everybody’s Talkin’ and Let It Be were fine enough in their own way. But it was the ten compositions from Withers’ own pen, including Ain’t No Sunshine, which grabbed the attention.

The combination of a voice with the soulfulness of Stevie Wonder and the folksy, singer-songwriter sensibility of James Taylor gave his music a unique appeal to black and white audiences as Laurel Canyon met the Watts ghetto. Ain’t No Sunshine gave him a million-selling hit single and won a Grammy for Best R&B Song.

Withers’ second album, 1972’s Still Bill, was arguably even better and included the No 1 hit Lean On Me, a tender and poignant gospel-inspired ode to friendship, which he explained was inspired by growing up in a poor but supportive rural community.

By now he was big enough to sell out New York’s Carnegie Hall and to join James Brown and BB King at the concert in what was then Zaire alongside 1974’s Rumble in the Jungle in which Muhammed Ali took back the heavyweight championship of the world bout from George Foreman. When Sussex folded in 1975, in what seemed like a good move at the time Withers signed with the far bigger Columbia Records. Instead, his experiences at the label led to him quitting the music business.

There were further hits including Lovely Day and Just The Two Of Us, a duet with Grover Washington, but by 1980 he had almost given up in exasperation at record label executives telling him what his music should sound like. “Blaxperts, I call ’em,” he said. “That’s the white guys who are supposed to have some kind of tap into your black psyche.”

When the label suggested he should cover Elvis Presley’s In The Ghetto, he refused on the grounds that his own songs were better. “I’m a songwriter. That would be like buying a bartender a drink,” he said.

When another executive told him “I don’t like your music or any black music, period,” he said he was “proud” that he managed to refrain from hitting him.

Between 1971 and 1978 Withers recorded seven timeless albums of immaculate songcraft, yet there was to be just one more record. After 1985’s Watching You Watching Me he went on strike. He wrote two songs for a Jimmy Buffett album in 2003 and another for a George Benson record six years later, but his own voice was never heard again.

There were no regrets. “I’m not motivated to draw attention to myself or travel all over the place. There was a time for that and when it was done it was done,” he said. “Back where I’m from, people sit on their porch all day.”

THE TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout