Moog music was adopted by the Beatles and changed our world

From Donna Summer to Doctor Who, the world would sound very different without the groovy synthesiser that was invented 60 years ago.

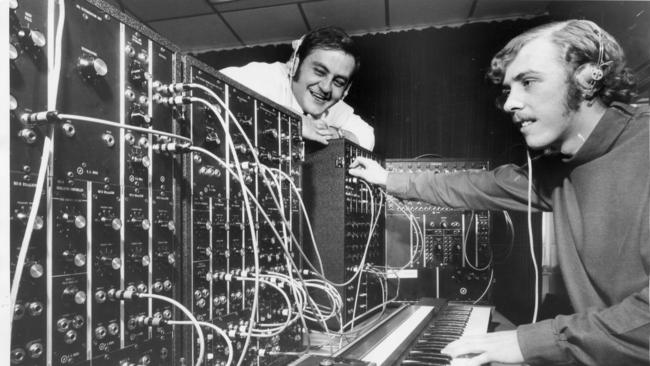

In 1964 a doctoral student from New York City called Robert Moog built a machine that could create and shape sounds by adjusting the voltage input. In doing so Moog took the scientific world of electronic music and placed it firmly into the mainstream. Sixty years on, with everyone from the Beatles to Karlheinz Stockhausen and Michael Jackson having got in on the act, the Moog has transformed modern music.

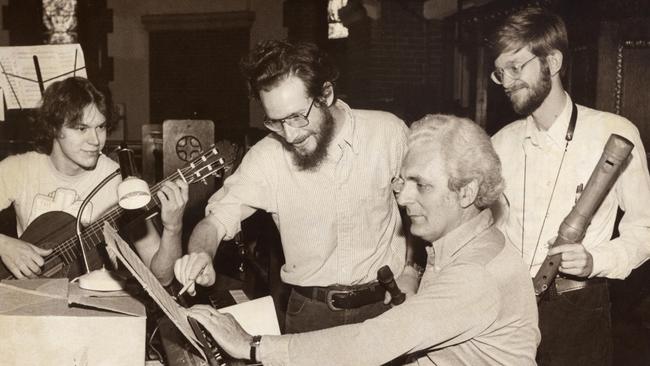

“It was the first mass-produced commercially available synthesiser,” says Will Gregory, co-founder of art-pop duo Goldfrapp, who is celebrating its 60th anniversary with an album by the Moog Ensemble, a nine-piece “orchestra” that uses the machines to their full potential.

“I Want You (She’s So Heavy) by the Beatles gets its character from a Moog. Giorgio Moroder made Donna Summer’s I Feel Love by pressing three buttons on a Moog that changed the key of the backing track,” Gregory says.

“By the mid-’70s all the funk bands were using it because it had such an amazing bass sound. It was a groovy machine.”

Pioneering American composer Wendy Carlos (originally known as Walter Carlos) recognised the Moog’s possibilities with Switched-On Bach, a million-selling album from 1968 that transposed 10 Bach pieces into an electronic setting. Carlos angered classical purists in the process, although Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys credited Switched-On Bach as “one of the most electrifying albums I have ever heard”.

Gregory sees it as the album that took the Moog out of the world of sound effects and into, as Carlos put it, “appealing music you could really listen to”.

“Initially Robert Moog didn’t even want to put a keyboard on the instrument because he wanted purity in sculpting the sound,” says Gregory, who argues that the real change came in 1970 with the introduction of the Minimoog: a portable, affordable version of the original synthesiser.

“The story goes that while he was on holiday the company put together a prototype Minimoog, after which he was won over. Once the Moog was out of the hands of the boffins, everyone could explore it.”

Moog was not alone in making synthesisers for rock stars. “When I started out computers were as big as this building,” Pete Townshend said when I spoke to him last week at the University of West London during an evening celebrating his bequest of a collection of keyboards, including the vast ARP synthesiser used on the Who’s 1971 classic Who’s Next.

“An amazing tutor called Roy Ascott predicted that computers would transform art and language, and this was in 1962. Twenty years later the Musicians’ Union were trying to ban synthesisers because they would put people like my dad (a former big band leader) out of work. It was clear that they were going to change everything.”

Then there was the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. The department’s most famous employee, Delia Derbyshire, came up with those incredible warping sounds we all know from the theme tune to Doctor Who.

“The Moog was a US thing so Delia used the VCS 3,” says Caroline Catz, the actor and director whose 2020 film Delia Derbyshire: The Myths and Legendary Tapes explores this pioneering figure’s life. “She used the first prototype British synth, the VCS 3, which was made in 1969 by Peter Zinovieff. It’s the same one Brian Eno used on the early Roxy Music albums.”

“There were parallel inventions by these eccentric characters around the world,” Gregory confirms. “For the VCS 3 you had a matrix pin board: to make the sounds you had to join the dots together with little pins. Russia had a synth called a Polivoks, which makes a howling noise, and the Italians had the buzzy Farfisa organ. There was an international arms race of synth design and the Moog influenced all of them.”

The Moog has been a big influence and inspiration for Gregory’s career. Turning electronic sounds into pop hooks was at the heart of Goldfrapp, formed with singer Alison Goldfrapp in 1999: their 2000 debut, Felt Mountain, was built around the effects a Moog could create. In 2005 Gregory put together the Moog Ensemble, initially to bring Carlos’s Bach arrangements into a live setting, and last month the ensemble teamed up with the Britten Sinfonia to perform everything from Bach’s Fugue in C Minor to John Carpenter’s theme to Escape from New York.

“We realised that by combining acoustic instruments with the Moog, one plus one made three,” he says. “That’s not a new idea – film composers like John Barry and Ennio Morricone have understood the possibilities of electronic music with orchestras since the ’60s – but I saw how much more there was to discover.”

Sixty years after the instrument was invented, Gregory’s hope is to use the Moog to its full capacity: in high and low art, classical and avant-garde, pop and the underground.

One of the classic Moog tunes is the frenetic, bleep-laden Popcorn from Gershon Kingsley’s 1969 album Music to Moog By; a version by the American studio band Hot Butter became a No.1 hit across Europe and Australia in 1972. Then there was Moog Indigo, a groundbreaking 1970 album by French composer Jean-Jacques Perrey. For much of the ’90s no night out was complete without the dancefloor going mad to that album’s EVA, an impossibly groovy instrumental redolent of space-age bachelor pads and utopian visions of the future.

Now, however, you can create anything you want on a computer. Where does that leave the Moog?

“I had an argument with someone about this recently,” Gregory says. “They were saying, ‘Why are you bothering with these old synthesisers when you can make anything digitally?’ Well, that is true – until you sit before a Minimoog, play a note and go: wow. The Minimoog has its own unique quality. The violin reached a peak of development 400 years ago. Sixty years ago, everything came together to make something – the Minimoog – that is enduring.”

THE TIMES

Heat Ray: The Archimedes Project by the Will Gregory Moog Ensemble is out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout