Interview: director Paul Goldman on his film Ego, a portrait of Michael Gudinski

Paul Goldman’s documentary offers an absorbing portrait of Michael Gudinski, a true believer who loudly and proudly beat the drum for Australian sounds for nearly 50 years.

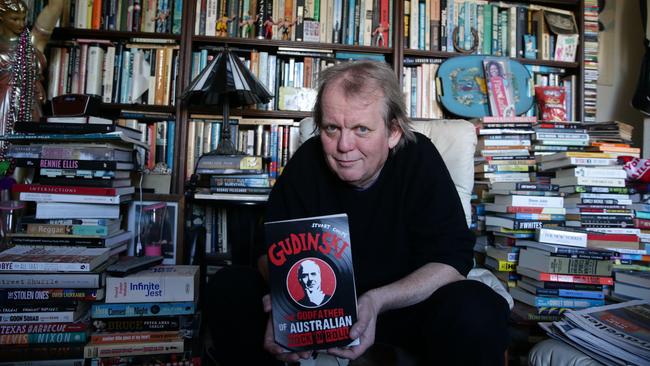

Michael Gudinski didn’t want a book about his life to be written and, in an effort to stymie it, put plenty of hurdles on the road to publication by asking his vast wide network of contacts to keep quiet and decline interview requests.

But when the Australian music entrepreneur realised he couldn’t stop it – nor its incorrigible author, Stuart Coupe – he became a reluctant participant in what was ultimately an authorised biography published in 2015.

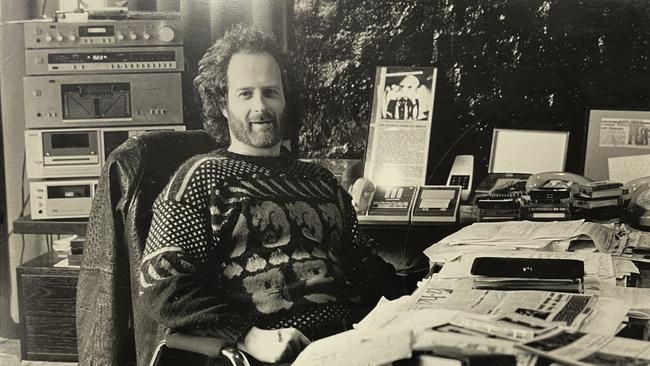

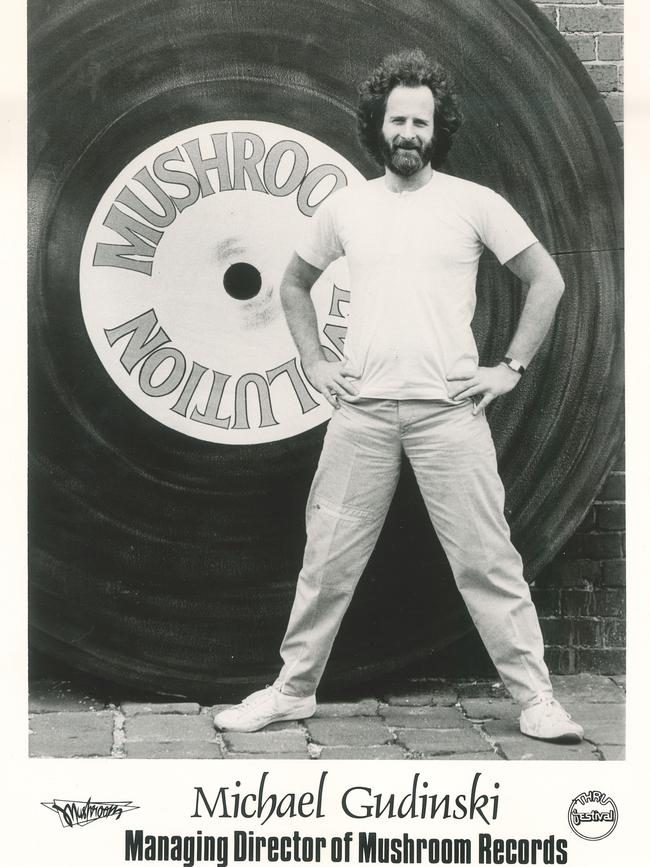

In time, despite his protestations, the subject came to develop a strange pride in those printed pages discussing and dissecting his business deals as the founder of Mushroom Records, the music company he co-founded in Melbourne in 1972.

“Michael realised he’d better say something, because Stuart was talking to all his enemies,” Paul Goldman told The Australian with a laugh. “And of course, when you went to Michael’s office, up that spiral staircase – which I’ve climbed too many times – Michael would open a cupboard, and there’d be a hundred copies of it, sitting there, which was something I always enjoyed.”

With a deepening of tone to mimic Gudinski’s famously gruff, barking voice, Goldman offered this impression: “I didn’t like this book, and I f..king wish he hadn’t written it – but do you want a copy?”

It was Coupe’s skilful literary excavation of a life devoted to promoting Australian music through Mushroom and its group of companies that cracked open the door for Gudinski to consider a screen version of his story, soon to be in cinemas.

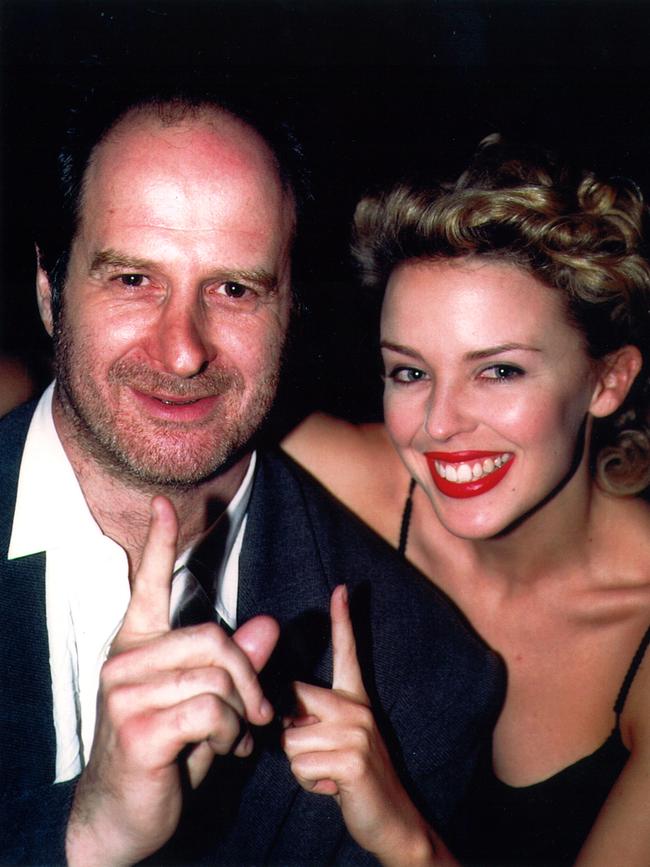

As with the book, there was reluctance – though in this case, the resistance was offered not by the titular subject but by Goldman, a filmmaker who has made more than 200 music videos for artists such as Silverchair, INXS, Nick Cave and Kylie Minogue. According to him, there was tension from the beginning of the project.

“Michael sent me a whole bunch of treatments that had come to him, unsolicited, for documentaries, because everyone realised that Mushroom’s 50th anniversary was coming up,” said Goldman.

“He asked me to read them and give him an opinion, so I read other people’s treatments – which I’m never comfortable doing – and said I didn’t think much of them. And then he got really pissed off on the phone and said, ‘Well, why don’t you f..kin’ make it?’. And I said, ‘Because I don’t want to f..kin’ make it’.”

Part of Goldman’s resistance was because he knew Gudinski well: their first encounter was in 1979, when he was a film school student who had made a music video for a song titled Shivers by rock band Boys Next Door, a forerunner to The Birthday Party and, later, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds.

On meeting at Mushroom’s Melbourne office, what followed was a typically expletive-laden music industry interaction of that era.

“I went there with the producer, who was also a film school student and a good friend of mine, Lucy Maclaren, who has gone on to have a storeyed career,” said Goldman. “Michael looked at what we’d done and said, ‘I want it’. We basically said, ‘You can’t have it; they own the copyright’. Michael said, ‘I don’t give a f..k’. Lucy said, ‘Go f..k yourself’; it was fractious from the moment we walked in the office.”

Yet like many before and after him, the filmmaker was drawn into the Mushroom orbit, through the push and pull of Gudinski’s alternately charming and blunt manner.

Goldman’s film credits include directing Suburban Mayhem (2006) and Australian Rules (2002), as well as 2010 documentary Such Is Life: The Troubled Times of Ben Cousins, about the former AFL star, for which Gudinski was executive producer.

Once more, despite his reservations, Goldman faithfully climbed that spiral staircase to Gudinski’s office, and they discussed a tentative film project.

“I was very reluctant, and I said I’d do it if I could do some very long, intense interviews with him, and deep-dive,” said the director. “Michael was a little bit concerned about that; about where I might go. But he understood that it was a chance to maybe have a final say, and right some wrongs, and set the record straight on quite a few things. I imagine he also thought it was an opportunity to have a dig at a few people. But we never got to do that.”

Gudinski’s sudden death in March 2021 changed everything. Their shared vision for a four-part, four-hour documentary was scuttled, and when Goldman resuscitated the project a few months later, it was clear compromises needed to be made.

“It was going to go into a lot more depth,” said Goldman. “I would have interviewed a lot more people, it would have taken a lot longer to make. But Covid came, Michael died, and I just felt like I had to honour the promise I’d made to him.”

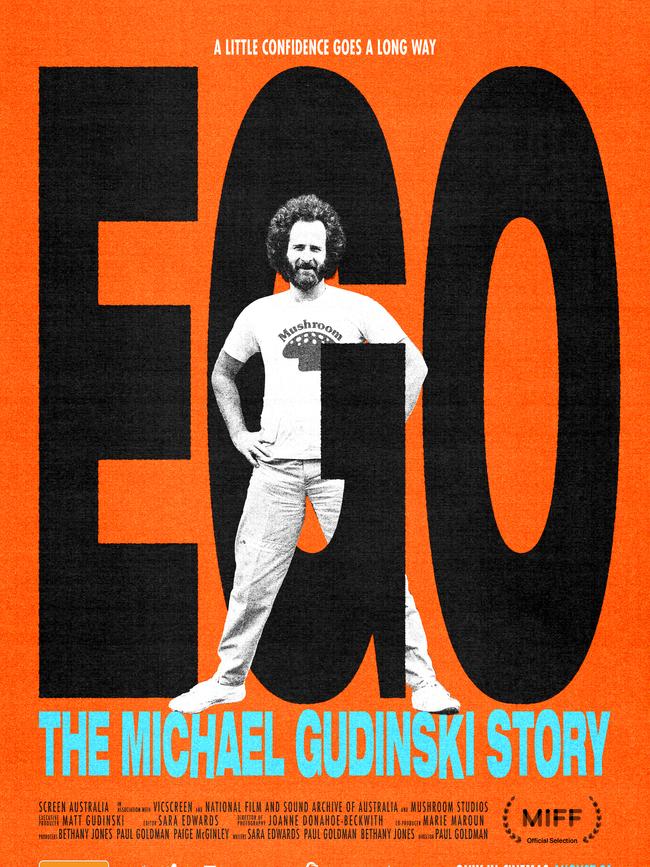

Ultimately, Goldman’s cut runs a little under two hours, and its title of Ego is a nod to Ego is Not a Dirty Word, a 1975 song by Melbourne rock band Skyhooks, one of many successful acts signed to Mushroom Records.

According to the director, the documentary was drawn from 120 hours of interviews and more than 1000 hours of sundry material from Mushroom’s 1972 formation onwards. “We were lucky that Michael, from the age of 19, loved the spotlight and publicity, and was never shy of the camera,” said Goldman.

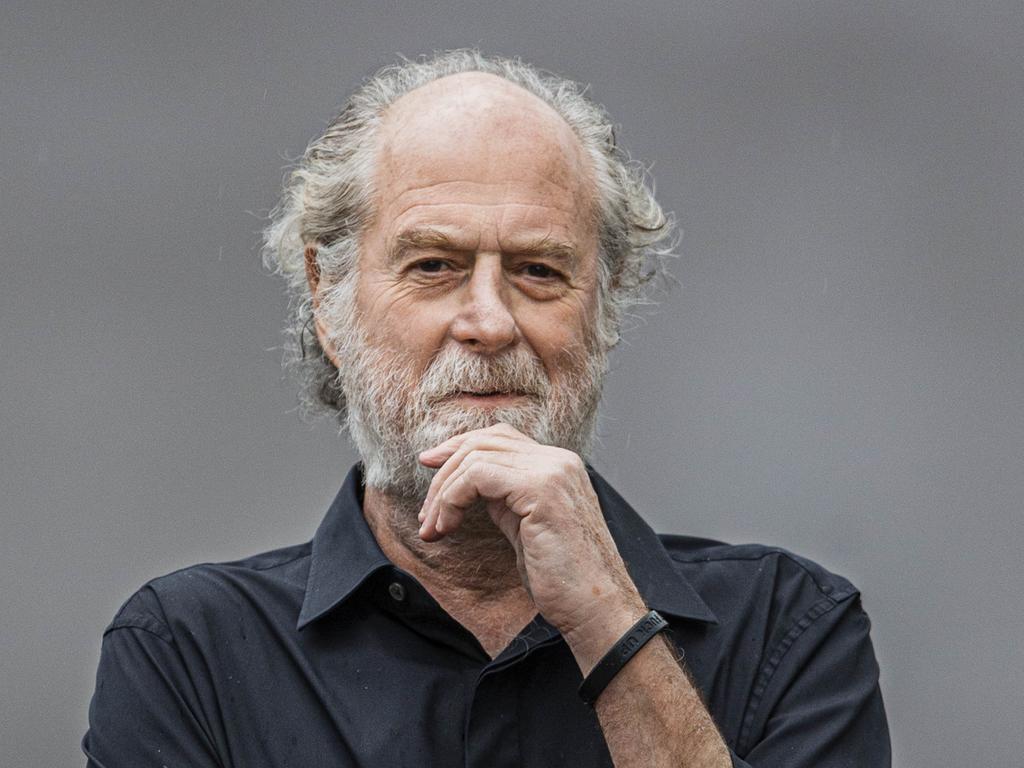

“He had been an incredibly loud – some would say obnoxious – advocate for Australian music,” he said. “So there was a wealth of archival material to dive into, but I found myself stopping to remind myself that he was dead. That’s pretty strange as well.”

When Gudinski died in his sleep at home in Melbourne, aged 68, it triggered an outpouring of grief across the Australian music industry and beyond.

A memorial service held at Rod Laver Arena was attended by performers including Kylie Minogue, Jimmy Barnes and Paul Kelly, as well as British pop singer-songwriter Ed Sheeran, who spent two weeks in hotel quarantine in order to be there and sing. (A poster in Frontier Touring’s office today, signed by Sheeran, bears this handwritten message: “Mikey! Thanks for taking me to stadiums. Mad c..t. Love, Ed.”)

Also at the memorial, video tribute messages were played on the big screens from the likes of Taylor Swift, Bruce Springsteen, Elton John, Billy Joel and Rod Stewart, all of whom were Frontier clients at some point.

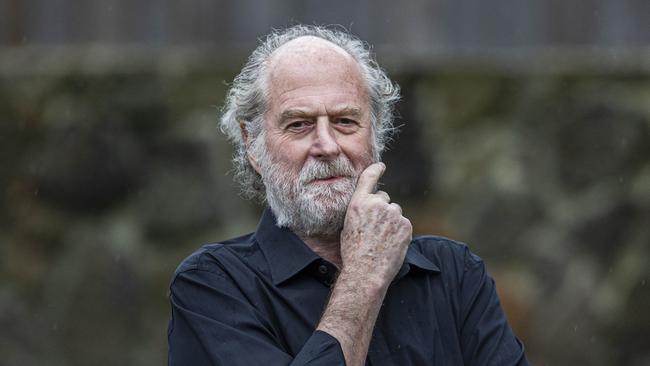

The director is upfront about how Gudinski’s absence changed the film’s tone. “When you make a documentary, you find yourself slipping into some pretty dangerous territory,” said Goldman. “I didn’t want to make a hagiography, so that really bothered me the whole way through. I was worried about interference from the family and other people, especially after he died.

“If Michael had been alive, I’m sure people would have had a real swing at him – but they didn’t. Some of the people who, on the phone, off the record, said, ‘I’ll come and be interviewed, but you won’t like what I’m going to say’ – then they’d sit in front of the camera, and they were as meek as little kittens.”

Goldman posits two reasons for this change of heart: firstly, people are generally reluctant to speak ill of the dead, no matter their flaws – and Gudinski had plenty of those, as he himself would admit.

Secondly, he said, “I also think that people probably realised the f..king significant contribution he’d made, and the legacy, and what it’s really worth.

“I mean, for any kind of venal or churlish opinions you might have about certain things with Michael, the achievements – across film, television, his advocacy for Australian music, his love of Melbourne – were phenomenal.”

As well, Gudinski’s death resurfaced some of his more quieter, principled stands, such as employing many talented, intelligent women at his Mushroom group of companies – a decision that was “very f..king rare in the music industry”, Goldman notes.

He was also a strong advocate for supporting Indigenous Australian artists, most notably Yothu Yindi and singer-songwriter Archie Roach, whose successes while signed to Mushroom were two of his proudest moments.

“A few people who were looking forward to the opportunity to come in and have a real swing at him, I think they probably had a deep, long think about it and realised that it would have just been churlish to do that,” said Goldman.

While Ego is no hagiography, it does tell a version of Gudinski’s life with some of the rougher edges sanded off. It is an absorbing, entertaining story of the biggest personality the Australian music industry has ever known, and Goldman can hold his head high for honouring the promise he had made to its subject and his resounding pride for the sounds made here.

“We still live in the shadow of the cultural cringe; it still haunts a lot of people – but not Michael Gudinski,” he said. “He just went, ‘F..k it – we make music’. I know there’s a lot of hyperbole and a lot of bullshit around this, but Michael was a true believer. He beat the drum very loudly, both here and overseas.”

It is fitting that the film will premiere this week at the Melbourne International Film Festival and tell the story of a proud, loud Melburnian.

And while it’s risky to presume the thoughts or behaviours of anyone after their death, Goldman is adamant his absent friend would be marshalling his considerable network of contacts in full-throated support for the Yes campaign for the Indigenous voice to parliament.

“I have no doubt that if Michael was alive, he would be organising concerts in all the capitals, on the same day, to support the referendum,” said Goldman. “I have no doubt. He would have thought that was such an important issue that he would have done something about it.”

Ego: The Michael Gudinski Story will be in cinemas August 31, following its premiere at MIFF on Thursday, August 10.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout