How snow chains created the sound of Bridge Over Troubled Water

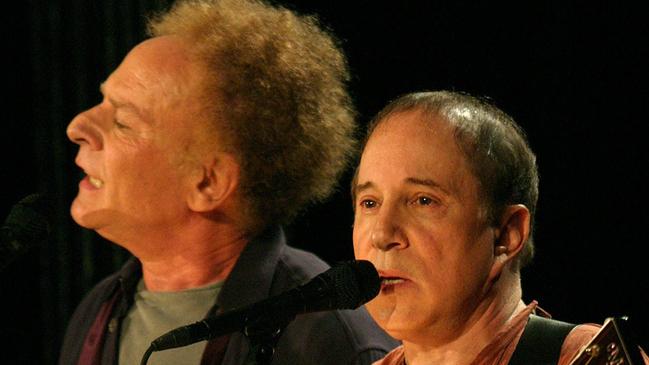

Paul Simon believes Bridge Over Troubled Water to be his greatest achievement, but it broke his partnership with Art Garfunkel.

It hasn’t snowed in Los Angeles since January 22, 1961, so very few of the city’s session drummers keep snow chains in the boot of their car. But Hal Blaine did. Good thing too. Late in 1969 he was called in to work on the final Simon and Garfunkel studio album, Bridge Over Troubled Water. The title track had evolved over the weeks from being the simple, hymnlike folk song that its author intended to a stately ballad that builds to a finale as irresistibly emphatic as Wagner’s The Flight of the Valkyries.

Simon and Garfunkel producer Roy Halee – his dad had been the voices of Terrytoons cartoon characters Heckle and Jeckle – was inspired by the passionate Phil Spector production of The Righteous Brothers’ Old Man River from four years earlier, which reveals its full dramas only in its final seconds.

Blaine understood where Bridge Over Troubled Water was to end up, but how to get to there? The song goes almost five minutes and we are 2.49 in before we even hear him – three distant cymbal crashes from a drum part brooding somewhere offshore. A few echoes persist. By 3.47 he’s back. By then he’d had an idea and been out to his boot.

“The ending of the song made me think of a man on a chain gang,” recalled Blaine towards the end of his long life. “It had that epic kind of feel that needed the right effect. So I got these big snow chains from my car and went back into this cement room in the studio and started banging them on the floor.

“On the two and four count, I’d slam them down, and on the one and three I’d drag them across the floor. Sliiiide-bang! Sliiiide-bang!”

Paul Simon knew the night he wrote it that he had a special song and he was so committed to getting it right that he and Art Garfunkel turned down the invitation to appear at the Woodstock festival, so they could work on it in New York City, not that far away from the upstate town hosting one of the epochal events of the 20th century.

The production then switched to Los Angeles where it would be completed by that city’s legendary Wrecking Crew squad of gifted studio musicians.

Simon was right about his song. It won Grammys for record of the year, song of the year, contemporary song of the year, and instrumental arrangement of the year. They also won album of the year and best engineered recording as Bridge Over Troubled Water went on to become the best-selling album ever, until Michael Jackson’s Thriller 12 years later.

But it was the moment that broke the partnership that had endured since school days for the boys born 23 days apart at the end of 1941 and who ended up living on the same street.

Simon first mentioned the song to Garfunkel not long before the pair started camping out at a rented house on Los Angeles’s Blue Jay Way – made famous the year before in the woozy George Harrison song written at number 1567. It was his “Yesterday moment”, he told Garfunkel. When it had more shape, he enthusiastically played him a tape. Of course, the appeal of the melody is universal, and Garfunkel picked up on that. At the end he urged Simon to sing it saying something like “It’s a great song. It’s your song. You sing it.” Their friendship was brittle by then; Garfunkel was off making films and, as always, Simon was writing the songs. They easily annoyed each other. Simon took Garfunkel’s comment as an insult. His partner in music had rejected his greatest creation. Garfunkel insists his comments were meant as praise for the composition. Simon told Rolling Stone in 1973: “He couldn’t hear it for himself. He felt I should have done it, and many times I’m sorry I didn’t …”

Simon started on the song after hearing a record at his friend Al Kooper’s house. Kooper played the famous, if simple, organ parts on Bob Dylan’s Like A Rolling Stone, and later put together Blood, Sweat and Tears. Kooper played his friend the antebellum spiritual Oh, Mary Don’t You Weep, by the Swan Silvertones, whose Claude Jeter could reach a striking crystalline falsetto. Towards the end – and certainly not in the lyrics of the song – Jeter calls out in a moment of devotional scatting “I’ll be your bridge over deep water if you trust in my name”. “I guess I stole it,” Simon said the following year and soon after sent Jeter, who claimed to have taken the line from the Bible, a cheque for $1000. He also invited Jeter sing the falsetto lines on his 1973 hit Take Me To The Mardi Gras.

It was Garfunkel and Halee pushing for the grand finish to Bridge Over Troubled Water, but it ran out of words before they arrived there. Halee asked Simon for another verse. Simon never worked that way; unlike Paul McCartney, his idol, who arrived in the studio with works in progress, and sometimes not, Simon wrote complete songs that were just to be polished there, at most.

Under pressure for more words to stretch out the grand production only he couldn’t see, Simon turned to something that had happened that morning. Looking into a mirror his new wife, Peggy Harper, had been distressed to see her first grey hairs. Simon came back in with: “Sail on silver girl, sail on by. Your time has come to shine. All your dreams are on their way.”

They couldn’t have been further from the white spiritual he had composed in the wake of the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy the previous year. Perhaps no other great song is so disjointed.

Ernie Freeman was brought in to arrange the orchestral parts. He had played piano on The Platters’ 1955 hit The Great Pretender, and won a Grammy for arranging Frank Sinatra’s song Strangers In The Night. When he handed around the sheet music to the players assembled to record Simon’s classic song, on the top was written what Freeman assumed to be its title: A Pitcher of Water. Those pages, with that title, are framed at Simon’s house.

During those days in Los Angeles, Garfunkel sat next to Larry Knechtel as he transcribed the song from guitar – on which its author had composed it – to piano. Knechtel, who had recorded with Elvis Presley, The Doors, The Beach Boys, and the Mamas and Papas, would share an arranging Grammy for his efforts, and his muscular chords do define the song (three years later he wrote and played the guitar solo on his band Bread’s single The Guitar Man, similarly changing its fortunes).

Bridge Over Troubled Water would top the US and UK singles and albums charts – it spent 33 non-consecutive weeks at No. 1 on the British album charts – but in Australia the single topped out at No. 2, kept at bay by John Farnham’s Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head, Shocking Blue’s Venus and The Beatles’ Let It Be.

Other than the song My Little Town which Simon wrote in 1975 and thought better suited his partner’s voice, they never recorded together again. And, notwithstanding some absurdly profitable reunion tours, they have spent the time since sniping at each other. Speaking after being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Simon said he regretted no longer being friends with Garfunkel. “I hope that one day, before I die, we will make peace with each other.” The audience applauded and whooped. Simon stayed at the microphone: “No rush.”

A few years later Garfunkel drove a final stake through their relationship, explaining to London’s Daily Telegraph that he had only befriended Simon at school because he was so short and felt sorry for him. “How can you walk away from this lucky place on top of the world, Paul?” he said of the partner who would no longer perform with him. “What’s going on with you, you idiot? How could you let that go, jerk?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout