Bondi to Hollywood and back: the story of singer Ben Lee

The prodigious songwriting talent who fell in with the Hollywood cool crowd, on returning to his roots and finding out what he loves most.

When Ben Lee’s 1998 record, Breathing Tornados, broke him in the US, the singer-songwriter declared his third release to be “the greatest album of all time”.

Back then, his ability to draw attention to his music with outlandish statements was seen as arrogance, but in fact Lee was taking cues from brash 1990s acts such as Oasis and experimenting with what became enduring interests for the young musician: cults of personality, self-promotion and social politics.

“I was brought up to believe in myself and believe that I could be successful at things,” Lee says by way of explanation. “It’s not nepotism, but the last few years have taught me that it isprivilege.

“Your early 20s is a feeling that you’re above what everyone else is doing … as you get older you can still believe that you have something special to offer, but it’s as valued as what other people have too.”

Now, at 42, Lee has transformed himself from a “precocious little c. t”, in the words of Powderfinger frontman Bernard Fanning, into an enduring Australian musical and cultural fixture.

Notwithstanding those late ’90s boasts, Lee enjoyed better commercial success at home with subsequent albums such as 2005 LP Awake is the New Sleep, which went double platinum in Australia and won Lee five ARIA awards, including best male artist, and single of the year for the relentlessly cheery Catch My Disease.

But it hasn’t always been a smooth ride for Lee, who has had a love-hate relationship with the mainstream music industry and experimented with religion, psychedelics and some questionable direct marketing.

Lee grew up in a Jewish household and attended the exclusive religious Moriah secondary school in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. He caught the attention of Waterfront Records and manager Steve Pavlovic, one of Australia’s best-known tastemakers, with his earliest demos.

Two solo records later, Lee was being introduced to the US by film star Winona Ryder and working alongside successful acts like the Beastie Boys, Ben Folds and Dan The Automator at the centre of American culture.

“On Breathing Tornados, I was exploring my frustrations with what I perceived to be the limitations of growing up in Sydney,” Lee says. “In this way only a 19- or 20-year-old who is projecting all their own limitations on to a city, or a tribe or their family, would be presumptuous enough to do.

“It’s a fundamental, heroic protagonist feeling.”

Sydney in the ’90s, Lee says “seemed square … I grew up seeing a lot of money around me, and it looked boring. I was looking for liberation”.

So he left. And by the time he was 20 he had an international music career and a circle of friends made up of the most famous entertainers in the US, so it’s no surprise Lee was caught in the rush of his own ego. He has since released a sprawling set of 18 albums – 11 as a solo artist and seven others under a variety of guises – and admits to having muddied his commercial footprint somewhat.

But a crisis of personality is on brand for Lee – after all, his first single was a devotional ode to the Lemonheads’ singer Evan Dando called I Wish I was Him.

Acceptance wasn’t easy to find in the music industry. Though initially welcoming of Breathing Tornados, some press in the US eventually rejected the hype.

Lee’s subsequent releases were brutally dressed down by critics and fellow musicians. Influential US outlet Pitchfork ranked Awake is the New Sleep — his biggest commercial success — at 2.9 out of 10 and levelled the staggeringly unkind criticism: “Like the class moron who turns out to be developmentally disabled, Ben Lee’s no fun to pick on anymore.”

In addition to the pain in his creative life, at 19 Lee lost his father, who died during heart surgery to repair a torn aorta.

In the years that followed, Lee joined what he describes as a cult, marketed essential oils and administered psychedelic treatments, and wrote music for dying people before finally finding himself in a happy marriage and back in show business. “Part of leaving the cults and spiritual stuff was getting real with who my community is, and that’s entertainers,” he says. “I was looking for meaning and connection in extreme places”, whereas now he recognises “my real community is people who like to get on stage and make people laugh, cry and swoon”.

Since moving from his family’s base in Los Angeles during the height of the US coronavirus outbreak back to Sydney, Lee has been busy re-establishing his presence in the Australian music industry. He has a new album in the works, I’m Fun, which features a cast of guest musicians including Jon Brion, Megan Washington, Zooey Deschanel, Shamir, Sadie Dupuis and Christian Lee Hutson. The first single was due this month but has been delayed.

Lee and actor wife Ione Skye (daughter of respected ’60s pop musician Donovan) produce a monthly evening of comedy, music and performance art at Sydney’s Giant Dwarf theatre – also on hold during the Sydney lockdown – called Weirder Together, which is an extension of the variety show they hosted at LA’s Largo Theatre.

The show is a chance for accomplished performers to try new things and experiment with their acts. “When you get up on stage, no one cares about how much money you’ve made,” Lee says.

“If I’m getting up to perform songs between Judd Apatow and Bo Burnham, I have to be clear about who I am and what I care about.”

Lee relishes his role as host. “I love art, but you know what I love more? Artists. To be surrounded by creative geniuses is one of the biggest gifts of my career.”

I met Lee for a coffee at a Paddington cafe around the corner from Five Ways, near his new home, before Sydney’s own coronavirus outbreak locked down NSW. “I’m interested in the smart, weird people,” he tells me. “What REM said – ‘The acceptable edge of the unacceptable’.”

He has always straddled interesting and contradictory worlds and values; he points out that the Bondi where he grew up was ungentrified and uncool.

“My entire psychology was formed out of where I lived,” he says. “I lived at the very top of North Bondi, where the golf course is.” Later, Lee would return to the top of his street for a photo shoot for this article.

“After World War II, my parents bought there in the ’60s, and no one wanted to live on the coast of the eastern suburbs because it was thought that the Japanese could bomb there. The area was working class.”

His father was on Waverley Council and into Labor politics and unions. “My dad would go down to (local pub on the beachfront) the Bondi Hotel to meet with constituents, and there were biker gangs,” he says. “But we were Jewish. All the family and people I went to school with were further up the hill in Vaucluse.”

His mother worked for the Department of Health, “getting vaccination information to non-English-speaking people”.

In an echo of his parents perhaps, Lee has spent a lifetime perfecting the ability to move between worlds. His ability to infiltrate complex scenes such as the American entertainment industry, gathering followers along the way, strikes me as quasi-political.

“In politics, you have to be able to meet the needs of different people, and some of them fall into conflict with one another,” Lee says. “I lived in between worlds, and still pride myself on being about to go uptown or downtown.”

He paints a picture of an early life typified by a yearning for transformation, personal dissatisfaction and the desire to turn into the rock stars occupying his fantasy life. “People want to get involved with someone who has a vision. It’s exciting, the feeling of being around somebody who wants something. It’s the reason why people get involved in cults.

“I knew there were gatekeepers in the music industry, and I wanted to meet and understand them. I was a student.

“I showed up in LA and Winona (Ryder) took me under her wing,” he says. “(I was) having late-night drinks with Lenny Kravitz and Fiona Apple. It felt appropriately insane in relation to my ambition … I was invited in, which is different to showing up with your guitar on Hollywood Boulevard and wondering ‘How do I get into the club?’. The reality that (later) hit me was how much hard work was actually involved.”

And yet when the young singer found himself at the place he wanted to be, he rejected it.

“I couldn’t accept that I was one of them. I would meet some famous person that I admired and act like a dick because I thought, ‘You’re just an entertainer’.”

The whole experience demystified the entertainment industry for Lee. “You look at Lenny Kravitz and it’s very glamorous. (But) if that guy is doing 80 shows a year, at least 60 of those are not in glamorous places. I think that dichotomy between escapism in the world of show business, and how real it gets in terms of self-confrontation, is incredible.”

If Lee’s music career has seen highs and lows, his romantic life was no less dramatic for a time.

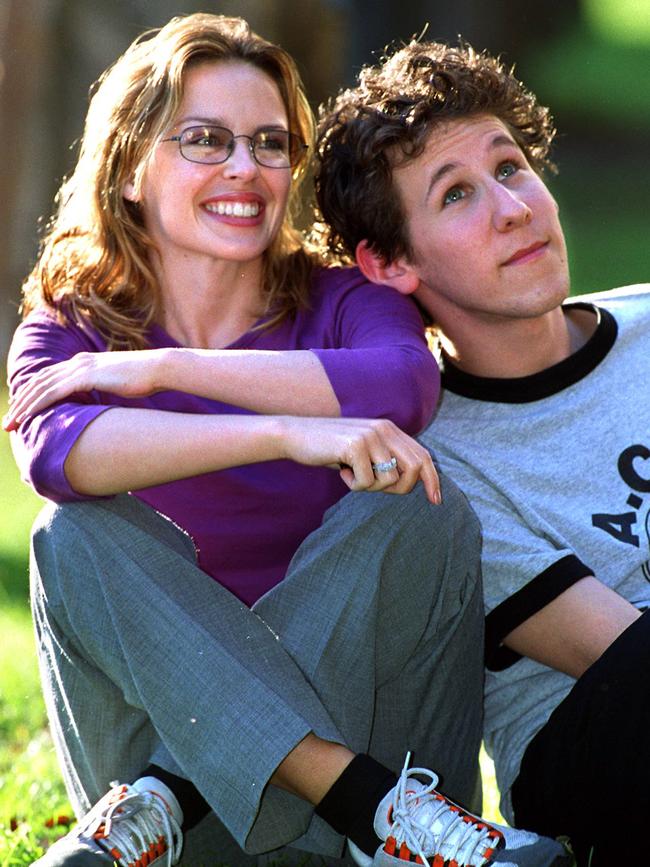

He dated Claire Danes in the late ’90s and early 2000s. Danes was a Hollywood ’90s “"It" girl” and with Lee as her career was going stratospheric. He’s remarkably forthcoming about that period of his life when asked. “Baz Luhrmann reached out while he was making Romeo + Juliet, about contributing some music. Claire was a big fan, she had talked about me in some magazines and things. I guess it was her form of witchcraft. Little did I know she had told friends she was going to marry me,” he says, laughing.

“While I was in LA, I sent a fax to thank Claire via her agent. Next thing she offered to take me out one night after the studio. She ended up taking me to Winona (Ryder)’s house. It was 1996 and there was no social media. Famous people’s lives were private.”

Danes and Lee lived together for six years, splitting up as their lives and careers took different paths. Lee recalls that he was off chasing crop circles in rural England as Danes formed a relationship with her then co-star Billy Crudup during rehearsals for a theatrical performance. “In the broadest sense, 18 is too young to pick a life partner,” Lee says.

“If you meet a couple that are wildly in love at 18, you almost hope they break up.

“We were both kids who started working really young and fell in love … we kind of parented each other through our late teens and early 20s. We were there for each other and it was us against the world.”

Danes had grown up in Manhattan, New York, the daughter of a sculptor and a photographer, while Lee was a Sydney boy with a relatively stable family life.

“Claire grew up in artistic chaos looking for stability,” he says. “I came from a middle-class background, looking to have my mind blown. We were a good match for an important period of our lives. At a certain point, though, you can’t stay a kid forever.”

After the relationship ended Lee became a devotee of Sri Sakthi Narayani Amma, the charismatic head of compound Sri Narayani Peedam in southern India. Joined by members of Empire of the Sun, Old Man River and Sydney indie band Gelbison, Lee made pilgrimages to offer his devotional support to Amma.

He married Skye – star of Cameron Crowe’s generation-defining film Say Anything – in a Hindu ceremony in India in 2009 following a long courtship that began as a mutual friendship via Skye’s ex-husband, Adam Horovitz of the Beastie Boys.

Despite the charitable works undertaken by the guru and his followers, Lee eventually saw a different side of the organisation and felt “a moral objection to the way Narayani Amma led his community”, he says. “There was a devotee who committed suicide. After his death, I watched the guru proclaiming that this devotee had ‘reached Moksha’ (liberation), meaning that he’d fulfilled his mission on earth. I thought this was an absolute bullshit move. For me, that was unforgivable.”

His disillusionment spiralled into an association with the wellness industry and a role peddling essential oils — a moment Skye remembers with embarrassment.

Sitting on the couch in their Paddington home, Skye visibly shudders when I mention the time the couple spent marketing the doTerra oils that promise to, among other things, rid the body of toxins. “That was embarrassing. That embarrassed me a lot,” Skye says, while Lee chuckles to himself.

“I didn’t really think Ben would lose his mind, but I began to wonder ‘What’s our life going to be like?’.”

Lee sees a line running through all of it. “There was never much difference between me at 19 saying ‘I’m Australia’s greatest songwriter’ and running off to India.

“It was all an experiment of persona and taboo – a lethal combination of my issues around giving away my autonomy and my fascination with these edgy experiences. People like me spread culture through our excitement about it. But we also spread faulty ideas, and get blinded by our own enthusiasm,” he admits – an echo of the politician. “It’s something I’ve learned to be on guard against as I’ve gotten older.”

In recent years he has embraced social media, using various platforms to persuade people against online cult QAnon and to champion causes adopted by the progressive left. “For black people in the US, who live in fear of being killed by police on a daily level, an honest reckoning with the racism at the heart of America is the only way forward. Australia has a similar need,” he says. “Larger conversations about racism and sexism (are) a massive step forward for our society,” he adds. He stresses that these sorts of campaigns are a long way from the “cults” he rebels against. “I view cults as being specifically about charismatic leadership and control,” he says. “I do not feel that there is a moral panic (with identity politics).”

Having had difficult experiences so young, and coming from the self-directed ’90s underground culture, it seems natural that Lee chafes against the commercial side of the music industry. “(In LA) Sia and I used to be around the same co-writing sessions and she was loving it … (but) I would come home from the sessions completely depleted, and thought, ‘This isn’t for me’.”

Yet Lee has played his version of the game successfully enough to survive, and to thrive back home – even as he was confronting the realities of a career in music in his 40s, before lockdown threatened live performance everywhere.

“I got an email from my booking agent, and he said: ‘Canberra’s a little light, we’re going to have to grow it’,” he says, laughing. “You have to be brought back down to Earth. A screaming crowd is the best feeling in the world, but it’s temporal.

“I’m a songwriter, but also open to adventures. I spent three days as a consultant in the writers room for Celeste Barber in a show about the wellness industry. I think about it all as creativity.”

Lee concludes that there’s nothing random about his choices. “There should be a powerful logic behind each decision,” he says. “Almost a rabbinical quality. (That’s) something that I took from my parents. I gave it my all, and that was the hill I died on. That’s the love of the game.

“Peers of mine, they all hit the target perfectly and had insane misfires … and that’s because they demanded and were afforded the liberty to indulge their impulses.”