Under the Volcano: The story of Beatles producer George Martin’s dream island recording studio

The extraordinary story of rock stars creating timeless art in the Caribbean is skilfully captured by a pair of Australian filmmakers.

Every Breath You Take by the Police. I’m Still Standing by Elton John. Money for Nothing by Dire Straits. Mixed Emotions by the Rolling Stones. The Reflex by Duran Duran.

At a glance, this may not look like much more than the beginnings of a great 80s-themed playlist of instantly recognisable songs. But there’s a common denominator in each of these winning compositions, and it has to do with where they were all recorded: a state-of-the-art studio in Montserrat, a small island in the Caribbean.

The island’s population today is tiny, and a fraction of what it was when famed Beatles producer George Martin established AIR Studios Montserrat in 1979. Why? Twin disasters: a hurricane followed by a devastating volcanic eruption.

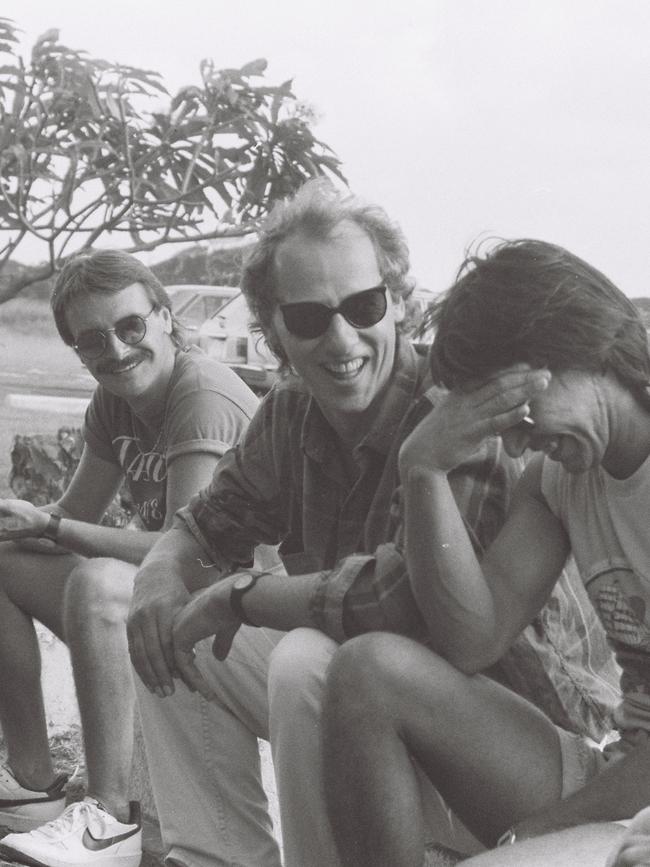

This extraordinary story of top-tier rock stars creating timeless art in paradise – followed by a fearsome showing of nature’s awesome power – is skilfully captured in Under the Volcano, the debut documentary feature by a pair of Australian filmmakers.

The idea was hatched by Fremantle-based producer Cody Greenwood, who recruited Sydney-based Gracie Otto to direct the film.

Featuring interviews with the likes of Dire Straits frontman Mark Knopfler and all three members of the Police, as well as sundry lesser-known individuals with deep personal connections to Montserrat, the in-depth documentary was a mammoth undertaking that was two years in development before Warner Bros Pictures picked it up for distribution.

The story had not been told at length on film, and Greenwood felt there was no one better placed to tell it than herself, given her personal connection to the famous studio’s history.

“My mum Frane Lessac was an artist on Montserrat in the 1970s,” Greenwood says. “She’d heard about this island where the harbour was too shallow for cruise ships, and jet planes couldn’t land because it was too mountainous.”

Lessac moved there a few years before Martin set up AIR Studios. She then made a living selling her artwork to the wealthy musicians who would go there to record.

“She later moved away, but we would always go back there when I was a kid,” says Greenwood. “When I started my company Rush Films, I thought this would be a good one as a first film out the gate, not quite realising the scale of trying to make something like this,” she adds with a laugh.

The first step the producer took was one that could have torched the entire idea, had the result gone another way. George Martin had died in 2016, aged 90, so the studio founder wasn’t around to give his blessing to the project or to share his recollections about AIR, an acronym for Associated Independent Recording, which he established in London in 1965.

So Greenwood penned a handwritten letter to his widow Judy, asking her to be in the film to speak on behalf of her late husband.

“Montserrat was his dream, and the island means so much to Judy Martin and to his children that, without them, this story just could not have been told,” says Greenwood. “The Martin estate ended up giving us all this amazing archive (footage), and Giles (Martin’s son) is such an important character – he knows so much about his dad’s life, and now he’s a music producer, too,” she says, adding: “If Judy hadn’t come back, or had said no, I wouldn’t have made the film.”

The contributions of Judy and Giles Martin are brief, but also act as a kind of emotional compass for the narrative.

For them, AIR Studios Montserrat wasn’t just a place to record music – it was the living embodiment of Martin’s post-Beatles decision to step back from being quite so hands-on in the control room.

Instead, he saw his role as creating a platform for artists and fellow producers to take advantage of the isolation of Montserrat to capture their best work, freed from the intrusive pressures of bustling cities and paparazzi.

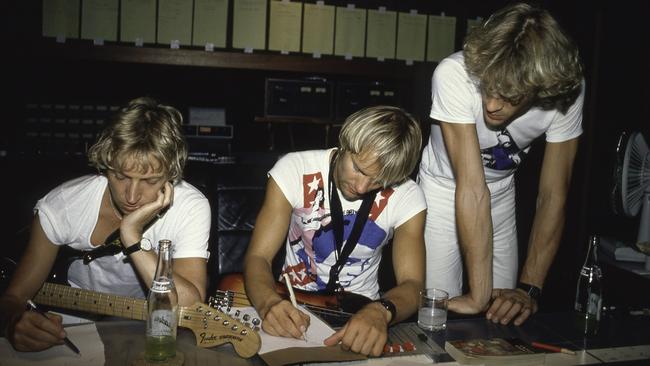

The Police recorded two albums there: 1981’s Ghost in the Machine, and Synchronicity, released two years later. At one point, guitarist Andy Summers visited Martin at his home on the island to see if he could help the famously fractious trio break their deadlock by coming on board as a producer.

Martin demurred, and instead told Summers that the three ambitious young men had it in them to nut it out together. And he was right: those words of wisdom from the older, experienced studio owner helped The Police get over themselves and get back to work.

“I love that Andy Summers is like, ‘We’re the biggest band in the world – why wouldn’t George Martin want to produce us?’” says Otto with a laugh.

“I think for (Martin), it was always about trying to find these creative environments, and find spaces and places for people,” says the director. “Even with the Beatles, he was this guiding presence that would enable people to be more creative.

“He spent a lot of time down there, and was just around; he produced a lot of the albums that were down there in the early days, and then he kind of just let it do its thing,” she says. “I always wonder what he would have done next in this life.”

In a true departure from normality for many of the artists who visited Montserrat, the locals weren’t overly impressed by the likes of Stevie Wonder rocking up at a local bar one night for an impromptu jam while on the island to record with Paul McCartney. If they were famous cricketers, rather than rock stars, it would have been a different story.

The final session recorded at the studio in 1989 was Steel Wheels, the 19th album by the Rolling Stones, which ended a three-year estrangement between the band’s co-founders, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger.

Soon after, Hurricane Hugo damaged 90 per cent of the buildings on the island, including the studio.

And when the previously dormant Soufriere Hills volcano began erupting in 1995, 19 people died and much of the island became uninhabitable.

As a result, most of the 10,000-strong population never returned to Montserrat; about 4000 settled in Britain. AIR Studios is still standing but the uninhabitable “exclusion zone” takes up about two-thirds of an already tiny island.

Naturally, the filmmakers had to travel there, pre-pandemic, to capture some footage that bookends what is an otherwise bright, sunny tale.

“We were there for about eight days, and we went pretty much straight away down to the volcano area,” says Otto. “We saw it as a Pompeii of the Caribbean. Drone footage allowed us to get closer to the volcano, because we could only walk in to about 2km.

“It’s an interesting contrast between the lush greenery of the mountains and the blue water – and then going down there, where it’s like a set from a film.”

Having visited about 10 times previously, Greenwood was itching to return to see how it looked post-disaster, too.

“We wanted the island of Montserrat to be a character in itself, and it is, with its post-apocalyptic landscapes and the black sand beaches,” she says. “I knew that we had to get down there, and we had to film the studio, because I’d seen photos of what it now looked like. It was so cinematic, and really eerie.”

For the filmmakers, the volcano became a metaphor for both the music industry’s move from analog to digital recording after 1989, and for the end of George Martin’s decade-long adventure running an isolated studio in paradise.

“As George Martin says in the film, everything has a period: you bring something out of nothing, and it always goes back to nothing again,” says Greenwood. “We really wanted to show that connection between the power of Mother Nature and the fact that we’re all essentially at its mercy.”

Under the Volcano will screen on digital platforms including iTunes and Amazon from September 1.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout