Archie Roach, pioneering Indigenous Australian musician, dies aged 66

As an Australian singer-songwriter whose music drew on his lived experience in the Stolen Generations, Archie Roach leaves a monumental contribution to the arts.

Archibald William Roach, AM, singer and songwriter, born Mooroopna, Victoria, January 8, 1956. Died aged 66 at Warrnambool, Victoria, July 30.

As a pioneering Indigenous Australian whose music drew directly from his lived experience as a member of the Stolen Generations, Archie Roach leaves behind a monumental contribution to the performing arts.

“We are heartbroken to announce the passing of Gunditjmara (Kirrae Whurrong/Djab Wurrung), Bundjalung Senior Elder, songman and storyteller Archie Roach,” said his family in a statement released by Mushroom Group at the weekend.

“We thank all the staff who have cared for Archie over the past month. Archie wanted all of his many fans to know how much he loves you for supporting him along the way,” said the family statement, which noted that his sons, Amos and Eban, have given permission for Roach’s name, image and music to be used, so that his legacy will continue to inspire.

“We are so proud of everything our dad achieved in his remarkable life. He was a healer and unifying force. His music brought people together.”

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said Australia had “lost a brilliant talent, a powerful and prolific national truth-teller’’.

“Archie’s music drew from a well of trauma and pain, but it flowed with a beauty and a resonance that moved us all,’’ Mr Albanese tweeted.

“We grieve for his death, we honour his life and we hold to the hope that his words, his music and his indomitable spirit will live on to guide us and inspire us.’’

Tonight we mourn the passing of Archie Roach.

— Anthony Albanese (@AlboMP) July 30, 2022

Our country has lost a brilliant talent, a powerful and prolific national truth teller.

During his 32 years in the public spotlight, Roach was a constant presence at concert halls, theatres and festivals. A series of health problems in recent years, including a grand mal seizure, a stroke and lung cancer, could not keep away from the stage.

His recording career began with his landmark 1990 debut album Charcoal Lane through to One Song, a track released in February - his final release - a sparsely arranged six-minute track telling a narrative that stretched back through time, linking ancient past and the present, and unintentionally tracing the full circle of the singer-songwriter’s life.

“Remember well what we have told you / Oh don’t forget where we come from,” he sang. “Mother Earth will always hold you / And we are born of just one song.”

It comprised only Roach’s soulful vocals while accompanied by two jazz musicians in guitarist Stephen Magnusson and double bassist Sam Anning, who joined him Roach at his final concerts alongside multi-instrumentalist Erkki Veltheim.

“I like it that way: sometimes less is best, and you don’t have to cover it with too many other instruments, so the song really stands out,” Roach told The Australian in February.

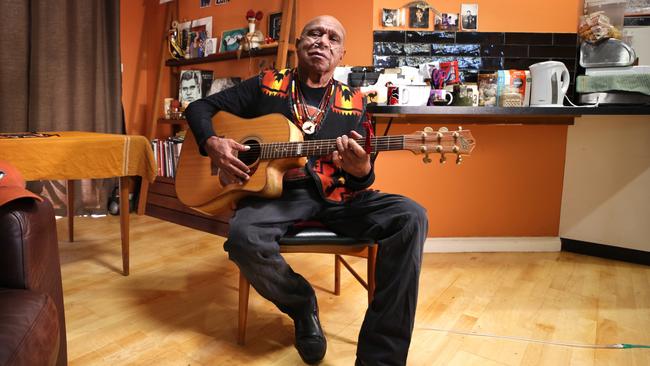

With a guitar, his voice, his story and what would end up being dozens of published songs, Roach set about quietly changing the course of Australian culture and the nation’s understanding of the Stolen Generations.

As far as the man himself was concerned, though, he was just one link in a long chain stretching back through history.

“I was a folk and country singer, but a lot of what my songs were about, blackfellas had been singing for tens of thousands of years, well before country music even existed,” Roach wrote in his engrossing 2019 memoir, titled Tell Me Why.

“The old people lost their brothers and sisters and parents, too; they also looked at the skies and wondered where they were and who had come before them,” he wrote. “They sang to create a sense of the great mystery of existence.”

“They sang in their language, along with the didgeridoo and clapsticks,” he wrote. “The only difference is that I sang in English, with a six-string guitar. The phrasing, language and instruments used are different, but I believed the emotion and soul of the music were similar.”

It was that undeniable sense of emotion that captivated people when they heard this quiet, humble man first sing into a microphone. But well before he became known as a musician, he had to experience the shock of a past that had been hidden from him.

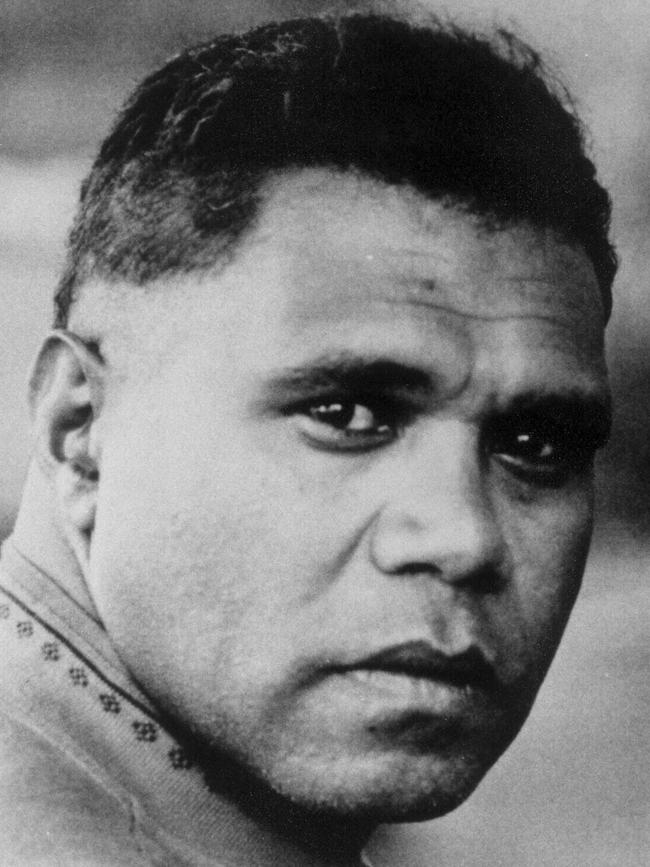

Born Archibald Roach in Mooroopna, Victoria on January 8 1956, he was removed from his family by Australian government agencies at the age of two. It wasn’t until he was 14 that he received a letter from a sister he didn’t know he had, about the death of the birth mother he didn’t know he had, which began to shine a light into the darker corners of his Stolen Generations family history.

After deciding to leave his kind and loving adoptive parents in Melbourne in search of connecting with members of his blood family in Sydney, Roach’s life on the road began, but it was littered with pitfalls: a significant amount of his late teens and young adulthood was spent self-medicating with alcohol while either sleeping rough or in temporary accommodation.

Encouraged by his partner and fellow songwriter Ruby Hunter, Roach began taking his abiding interest in telling stories through song seriously. “It was concerned about the people around me whose pain and joy I felt so deeply I had to write about them,” he wrote in Tell Me Why. “Empathy was my impetus.”

Three pivotal events in the space of three years led to his career as a singer-songwriter.

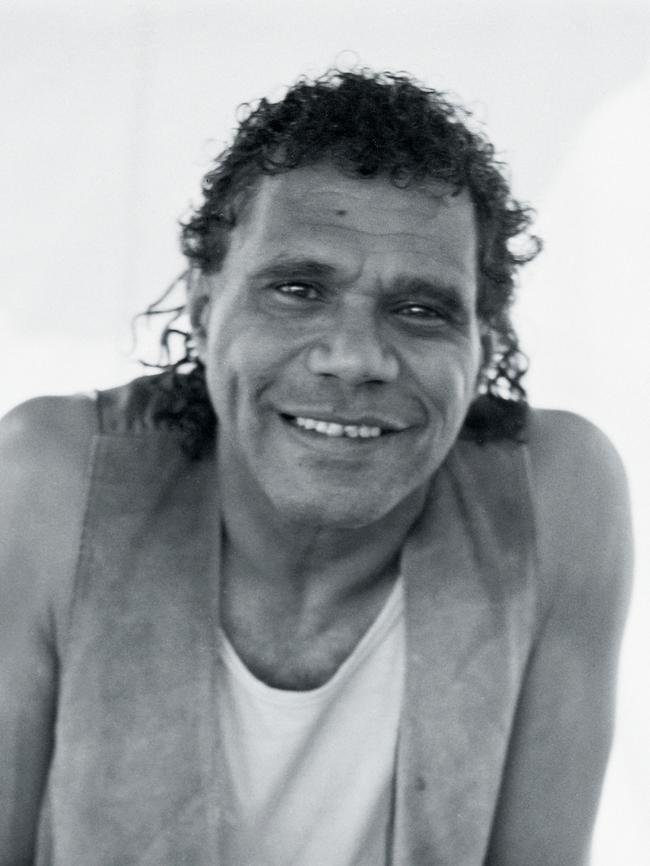

The first was in 1988, when Roach was 32. At the Survival Day events held at Sydney’s La Perouse parklands – chosen due to its proximity to the approach into Botany Bay, which Captain Cook and crew had undertaken 200 years earlier – he took his guitar on to a stage and played something very few had heard before.

It was called Took the Children Away, a landmark song about the Stolen Generations, and its memorable opening lines were these: “This story’s right, this story’s true / I would not tell lies to you.”

Recalling the song’s live debut in his memoir, Roach wrote, “As soon as those lines were out, I felt no fear, no trepidation. I was alone in my thoughts. The crowd was somewhere else. My mind was on my old dad and mum, and my brothers and sisters, and uncle Banjo.”

“I didn’t try to sing to impress, or to educate,” he wrote. “I sang to honour. This is something I think I learnt sobering up. Respect and truth are the cornerstones of my life now, and when I played, I played to respect the stories. I did that by playing them true.”

Soon, others began to take notice of those stories, particularly singer-songwriter Paul Kelly and guitarist Steve Connolly, who happened to catch a performance of what would become Roach’s signature song on ABC TV.

This link led to the second pivotal moment in Roach’s life, when he was asked to open for Kelly and his band, the Messengers, at Melbourne Concert Hall (now known as Hamer Hall) in 1989; a major coup for a largely unknown performer.

There are a few moments in Australian live music history that deserve to be cherished, and this is certainly one of them.

Roach’s 20-minute set ended with Took the Children Away, and Kelly has recalled watching from the side of stage, goosebumps prickling his skin and the hairs rising on the back of his neck, as the song ended and a stunned silence befell the room.

The man leaving the microphone thought he had bombed, but the quiet was eventually punctuated by a building wave of applause unlike anything he’d heard before. Roach had arrived.

His third breakthrough occurred when Kelly and Connolly offered to record and produce his songs, which would become his debut album Charcoal Lane, released in 1990 by Mushroom Records.

Speaking with The Australian about Mushroom founder Michael Gudinski after his sudden death aged 68, in March last ye, Roach said, “He gave me a chance, back 30-odd years ago, to record. [Gudinski] could have easily said ‘No’, especially songs like Took the Children Away; ‘That’s too political’. But he took it on board, and if it wasn’t for him, I suppose I wouldn’t be a recording artist.”

His musical success, when it came, was never the sort that saw him topping pop charts. After winning two ARIA Awards in 1991 for Charcoal Lane, including best new talent, he instead slowly drew in a wide national audience of folk, country and roots fans who thrilled to his singular style of story-songs.

He had met his life partner, Ruby Hunter, in Adelaide when they were both homeless teenagers. They had two children together, and fostered many more; Roach was bereft when she died suddenly in 2010, aged 54.

What Hunter saw better than anyone was the value, importance and resonance of her husband’s achingly personal songs, and how recording them might help other Indigenous Australians hear his voice and walk through the door that he cracked open.

Twelve years after her death, his final work, titled One Song, was included as the final track on a 44-song anthology of his work across the decades, titled My Songs: 1989-2021, released earlier this year.

“It’s an interesting idea to have a song like that, which is the beginning, being the end,” Roach told The Australian in February. “From Took the Children Away, it’s come full circle to One Song. It’s almost like confirming to yourself that you haven’t forgotten where you come from; I realise I was born of just one song.”

After a string of health concerns in recent years, his oxygen tank was a constant companion, as reliable as a heartbeat and such a fixture of his life by then that he was way past feeling self-conscious about his nasal cannula.

“It’s just who I am now,” said Roach of the hardware in August last year. “It helps me to sing, to talk and to share stories with people. It certainly is a lifeline – but as well, it’s something that just enables me to do what I love to do.”

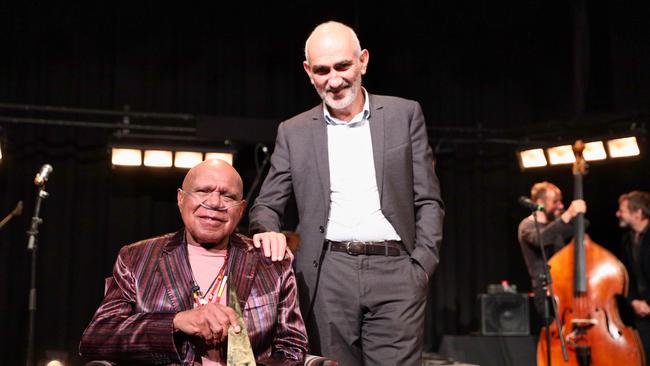

He was inducted into the ARIA Hall of Fame in November 2020, but even making it to one of the major moments of his career was touch-and-go, after Roach’s health took a turn for the worse and he ended up in hospital not long before he was due to be honoured.

But he pulled through, and performed in a stunning group reading of Took the Children Away at the Lighthouse Theatre in Warrnambool alongside Paul Kelly and others, for what was one of the most moving and memorable moments in our music history.

Survived by his sons, Amos and Eban, his life in music perhaps more hard-earned and well-deserved than any other Australian artist of the past three decades, and his boundary-smashing actions went on to inspire the following generations of Indigenous artists to pursue their art and find significant audiences, just as Roach did.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout