Two billboards outside Holt Summit, Missouri: the true story

The movie Three Billboards echoes the true story of a Missouri mother determined to solve the mystery of her daughter’s disappearance.

A few weeks ago, Marianne Asher-Chapman went to see Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri, with some girlfriends who had called to alert her to the movie.

In the dark of the cinema in her hometown of Holt Summit, Missouri, the tiny blonde woman, aged in her 60s, watched a story so similar to her own she was, she says, “blown away.”

Three Billboards is the story of Mildred Hayes, a desperate mother grieving over the rape and murder of her daughter Angie. Furious at the slow progress of the police investigation, Mildred rents three billboards near her home, their messages ‘Raped while dying,’ ‘Still no arrests?’ and ‘How come, Chief Willoughby?’ intended to pressure the local officers into action.

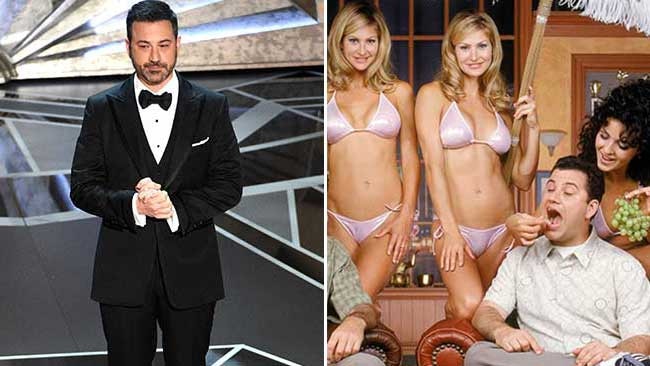

Martin McDonagh, director of the Oscar-nominated film, says he was inspired to write it after seeing billboards about an unsolved crime “somewhere down in the Georgia, Florida, Alabama corner.”

But his film’s story also echoes the true, and tragic story of Ms Asher-Chapman and her daughter Angie.

Over 14 years ago, in November 2003, Angie — who shares her name with the victim in Three Billboards — mysteriously disappeared on the day of her niece’s fifth birthday party. Days earlier, Angie, aged in her early 20s, had shown her mother the presents she'd bought for the little girl and the older woman knew she wouldn’t miss the party for the world.

Ms Asher-Chapman was also fighting throat cancer at the time and “I just knew she wouldn’t leave me through all that,” she told local media at the time.

But Angie never showed up, never answered the increasingly frantic messages her mother left on her mobile.

A week her disappearance Angie’s husband Michael Yarnell arrived on Ms Asher-Chapman’s doorstep and told her that his wife had left him for another man.

“He said; ‘I came home the other day and she was gone, I guess she has run away with another man,” Ms Asher-Chapman told the BBC this week. “I asked him ‘Why would she do that?’ She’d never leave her two beloved dogs. But he just said he didn’t know.”

Everything her son-in-law was telling her sounded wrong and rang immediate alarm bells. “Right there and there I thought he had a connection with her going missing. I asked him if he’d filed a missing person’s report and he said no because she wasn’t missing, she’d just run away.”

That started Ms Asher-Chapman’s long search for the truth about her daughter’s disappearance, and her search — which is still ongoing — for the young woman’s body.

But, like the movie’s grieving mother Mildred Hayes, from the very start Ms Asher-Chapman came up against a recalcitrant police force that showed little interest in her daughter’s fate.

“I had to argue with the police just to file a missing person’s report,” she says. “They didn’t want to do it. Every day I would call them up but real quickly I felt too intimidated to call them. I was made to feel I was bothering them.

“For five years I was hearing from this one detective; ‘No body, no crime.’ He insisted she had run away with another man.”

Ten days after Angie’s disappearance, Ms Asher-Chapamn’s certainty was shaken when a postcard arrived postmarked from Arkansas, and signed with Angie’s name. “It said: ’Gary and I are on our way to visit with his family. We’ll write once we’re settled.’ But although it looked like Angie’s handwriting it also looked strange, not really hers at all.” Plus, Angie had ever mentioned a ‘Gary’ to her mother.

Despite her doubt about the postcard’s authenticity, Ms Asher-Chapman took it to the police, who closed the case.

But she kept digging. She started her own investigation with one of her siblings, she contacted all Angie’s friends and, like Mildred Hayes, she rented billboards outside her town of Holt Summit and covered them with blown up flyers.

Her billboards didn’t attack the police as those of Hayes did; but the flyers, showing a huge picture of Angie, hung there in silent reproach at the perceived police failure to investigate.

She told anyone who’d listen about all the factors that made her daughter’s disappearance suspicious; Angie would have told her mother if she was having an affair, Mr Yarnell’s truck disappeared the week his wife did and a wall and part of the floor in the trailer the couple shared had been replaced for no apparent reason.

Under pressure from this stubborn, angry woman, the police eventually re-opened the case but the investigation continued to drag, with officers seemingly reluctant to take it anywhere.

“A couple of officers were sympathetic but what went against Angie was that she was living in the town of Ivy Bend which was arguably the most poverty stricken, drug ridden area in the state” she says. “I think that was a big part of it.”

In 2008, five years after her daughter went missing, Ms Asher-Chapman sent the postcard to a handwriting analyst in Texas who confirmed that the card hadn’t been written by Angie but by her husband.

Shortly afterwards Ms Asher-Chapman took her story a step up from the billboards, appearing on national television; and days later, Yarnell disappeared. “For the first time the police took an interest, and listed him as a missing person.”

Yarnell was finally tracked down in 2008 after police took a call from someone who had seen him at an airfield in Biloxi, Mississippi.

He was extradited to Missouri and eventually confessed that he had killed his wife — but insisted it was by accident.

According to Yarnell, Angie had fallen off the back deck of their home during a fight. He said she’d attacked him and in defending himself he accidentally pushed her off the deck where she hit her head and died. His story was that he panicked and put her body in a canoe, rowing to an island upstream. Once he got to the island, he said, he didn’t have the strength to drag her body ashore and it fell into the water. So he went home and concocted his story about the incident.

In 2009 Yarnell was convicted of involuntary manslaughter, sentenced to seven years and served just four.

But even after Yarnell was convicted Ms Asher-Chapman kept up her search — this time for her daughter’s body. The flyers came off the billboards but she put a shovel in her car and in the fine weather would dig up the fields around her daughter’s former home, looking under trees, in sink holes and abandoned homes.

She visited her son-in-law in prison, begging him to tell her where Angie’s body was so it could be retrieved and given a burial but he stayed silent.

Her worst moment came in 2013, weeks after Yarnell was released, when she literally bumped into him in a supermarket. “He asked me how I was doing and I said not too well because it was 10 years since she disappeared and I still didn’t have a body.”

Then she got into her car and parked by the supermarket door. “I parked in a handicap spot and I sat there for 20 minutes, waiting to run him over when he came out of the store. But then something snapped and I drove away.”

Ms Asher-Chapman is still searching for Angie’s body. She still has green and yellow ribbons tied around the trees in her front yard, she is still haunted by the tragedy.

She never knew about Three Billboards until long after its release, when friends called to tell her that its plot could have come from her life.

Watching the film one scene in particular stayed with her; a scene where Mildred is tidying the flowers growing under one of the billboards and she looks up to see a big doe watching her.

“That has happened to me time after time,” she says. “From the very beginning the deer would come to me. I always saw it as a sign.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout