I looked into Liz's violet eyes

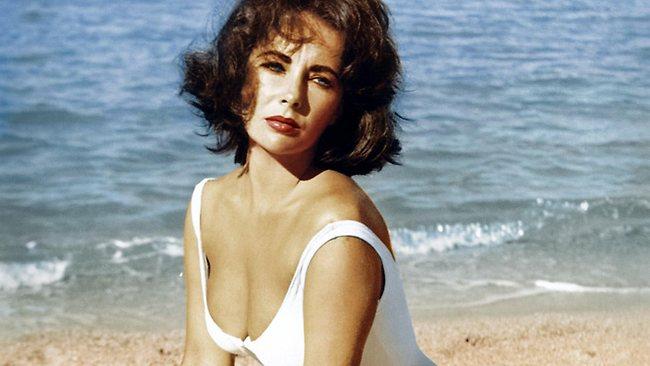

SHE was not the greatest actress but Elizabeth Taylor had a magnetic presence.

THE 1973 San Sebastian Film Festival in Spain opened with one of Elizabeth Taylor's lesser efforts, Night Watch.

The only reason such a prestigious festival would screen such a poor film was that Taylor had agreed to attend in person, and star power is not to be discounted.

The screening was due to begin at 10pm but, thanks to Taylor's notorious reputation for being late, no one was surprised when it turned 11 and the star had still not arrived. I was in the audience that night, sitting with theatre and film pioneer Rouben Mamoulian, who was chairman of the international jury. After his experiences with the actress on Cleopatra 12 years earlier, it's not surprising he became visibly annoyed as the minutes ticked by, but he kept his sense of humour.

"They certainly gave the film an appropriate title," he muttered.

Finally she arrived, apologised, made a gracious speech, and the screening was under way. Two hours later I was ushered into her presence at the official reception and found myself transfixed by her famous violet eyes. I have never seen eyes of that colour before or since and I don't believe cinemagoers were able to appreciate how remarkable they were.

She was, of course, one of the most glamorous Hollywood stars. In the early days of World War II, in Los Angeles, the child actress attracted the attention of casting directors first at Universal and then at MGM, where she remained under contract for several years. Her early roles in family favourites such as Lassie Come Home (1943) and National Velvet (1944) made her immensely popular the world over.

She effortlessly made the transition to teenager, then to young adult, making an impression in the 1949 version of Little Women; and, in her first significant adult roles, as the daughter of Spencer Tracy in Vincente Minnelli's sublime Father of the Bride (1950) and its sequel Father's Little Dividend (1951), she became a star.

Yet MGM didn't seem to know what to do with her. She was, perhaps, too beautiful, and it was generally considered her acting range was limited. As a result, many of the films she made for the studio in the 1950s - The Girl Who Had Everything, Rhapsody, Beau Brummel, The Last Time I Saw Paris - could have been made by anyone.

There are a couple of standouts in this period: in George Stevens's magnificent version of Theodore Dreiser's An American Tragedy, retitled A Place in the Sun (1951), she brings rare depth to the potentially shallow role of the rich girl who falls in love with the poor young man, a tormented Montgomery Clift; and in the swashbuckler Ivanhoe, made the following year, she is touchingly vulnerable as a Jewish girl at the centre of the drama. Then came Elephant Walk, a melodrama set in Ceylon (as it then was) in which she plays, with considerable feeling, the unhappy young wife of plantation owner Peter Finch. It was a role she stepped into after Vivien Leigh, the original star, had left because of illness, and Leigh can still be glimpsed in long shots during the film's exciting climax.

It was Stevens's Giant (1956) that finally convinced sceptics that Taylor should be taken seriously as an actor, and her scenes in this epic with Rock Hudson and James Dean are memorable. Her close friendship with gay actors such as Hudson and Clift, with whom she made another epic, Raintree County, in 1957, undoubtedly encouraged her to work on behalf of AIDS sufferers in later years.

She startled audiences with the maturity with which she played the title character in the watered-down film version of Cat on a

Hot Tin Roof (1958), and was amazingly sensual in Suddenly Last Summer (1959), directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz; in what was, at the time, an exceptionally explicit film, she plays opposite Clift and Katharine Hepburn. The following year she won her first Oscar playing a callgirl in the bland Butterfield 8.

By this time her private life was notorious. She married hotel heir Conrad "Nicky" Hilton Jr in 1950 when she was 18, divorced him and in 1952 married British matinee idol Michael Wilding, then, in 1957, married producer Michael Todd, whose death in an air crash in 1958 widowed her. Her "stealing" of singer Eddie Fisher from his young wife, Debbie Reynolds, caused a scandal; she married Fisher in 1959.

The production of Cleopatra is a saga all of its own. It started under the direction of the enormously talented Mamoulian, with Peter Finch as Caesar and Stephen Boyd as Mark Antony. Taylor's now habitual lateness and tantrums led to long delays, and when she was taken seriously ill the production was abandoned for a time. When it eventually re-started it was under the direction of Mankiewicz (Mamoulian never made another film) and Rex Harrison was cast as Caesar and Richard Burton as Antony.

The much-publicised romance between Taylor and Burton led to her divorce from Fisher in 1964 and her fifth marriage the same year. Taylor and Burton co-starred in several more films, most notably Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) and The Taming of the Shrew (1967), films that showcase a new level of maturity for Taylor as an actor. Was Burton, a fine classical actor, responsible for this? Did he coach her and encourage her to find the resources to play these roles? Or did she, as some believe, damage his career, dragging him down to her level in routine assignments such as The VIPs and The Sandpiper?

At any rate, the tempestuous marriage lasted 10 years. They divorced in 1974 but remarried in 1975 and divorced again in 1976.

Subsequent Taylor roles are of little interest, except for Joseph Losey's creepy Secret Ceremony (1968), a film much censored on its original Australian release, and John Huston's full-throttle Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967), in which Taylor played opposite Marlon Brando. She made some films in the 70s and 80s, but as she got older she seemed to lack the enthusiasm, and she directed her energies towards other causes: representing a perfume company, championing AIDS awareness and being a very public friend of pop star Michael Jackson.

Maybe she wasn't the greatest screen actor: she was no Davis or Hepburn. But I have no doubt she was one of the world's most beautiful women.