History hangs in the rebalance: the National Gallery of Australia moves towards a full rehang of its collection

Nearby, Augustus Earle’s 1826 portrait of Bungaree looks out near a 1975 photograph by Mervyn Bishop, the one that shows Gough Whitlam pouring soil into the hand of Vincent Lingiari. Sombre landscapes by Eugene von Guerard and mourning scenes by Robert Dowling are combined with a poignant 2005 painting by Julie Dowling, feather armbands from northeast Arnhem Land and an 1847 daguerreotype of an Aboriginal man with two younger companions.

Stand back from all this and the picture becomes clear: the National Gallery of Australia is changing in fundamental ways. Its new treatment of what once would have been its 19th-century Australian display now stands as a guide to the way director Nick Mitzevich wants to reimagine the gallery as a whole. “It’s sort of like the tasting plate of where we might go,” Mitzevich says. “I’m playing the long game here.”

The national collection gradually is being reconfigured as a living, breathing display, a contest of ideas to challenge the wisdom of the past. Starting with 19th-century Australian art, Mitzevich says he wants to use the collection to “review and revise” the gallery’s approach to art history.

He also wants to remove many of the artificial barriers used to segment work — time, geography, medium — to tell a story with greater nuance and relevance for visitors. “With art,” he says, “I don’t think there are rules. There’s a canon of art and there’s an accepted history, but it’s our jobs to review it all the time.”

Mitzevich, who took over as director 18 months ago, calls this a “transitional moment” for the gallery. The new display, Belonging: Stories of Australian Art, is a small but ambitious spread. It opened quietly on level one early last month, and it’s the first step towards a full rehang of the gallery’s collection.

Several curatorial departments worked together on Belonging, a process the director intends to repeat across the next two years.

“When we do a much more comprehensive approach,” he says, “we’re going to use a similar methodology where we’ll look at history from multiple points of view rather than following the prescribed art canon.”

Belonging features 170 works by indigenous and non-indigenous artists, ranging from painting to video, photography, sculpture, prints and silverware. It brings together historical and contemporary work to “reconsider” colonisation in Australia.

According to the curators, this is a story that doesn’t privilege a settler narrative. So instead of opening with, say, a European perspective of a strange new land, one of the first works in the show is a three-channel video work by Christian Thompson from 2017.

Curators are relying on the nonlinear notion of “everywhen”, where past and present and future exist simultaneously. This is a sentiment echoed in the Charles Perkins quote printed on the wall: “We know we cannot live in the past but the past lives in us.” It also recalls a 2018 show at the National Gallery of Victoria, Colony, which examined Australia’s colonial past from different points of view.

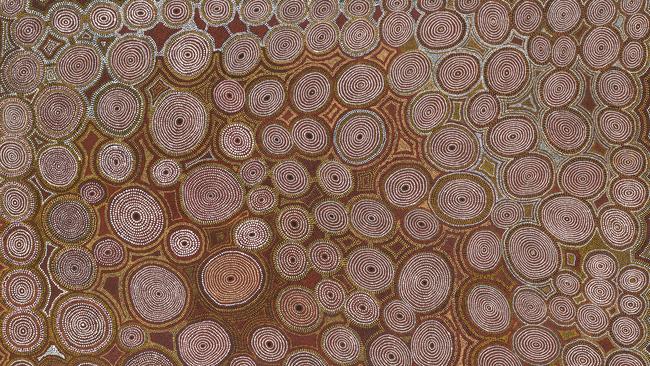

Hence the combinations across time. Anatjari Tjampitjinpa’s bark from 2008, Driving Around Warrang/Sydney, hangs near works by John Glover and Conrad Martens — the common ground is that all the artists are responding to a landscape both familiar and utterly foreign.The gallery also has made a key change relating to attribution. Since many of the objects are attributed to indigenous people whose names were not recorded, the gallery is now using the term “ancestors” instead of “unknown” artist. Non-indigenous artists are still referred to as “unknown”.

The work on Belonging also has focused attention on gaps in the NGA collection. “It’s the first step in having a dialogue with our audience about how we tell different stories,” Mitzevich says.

Visitors to the gallery next year will encounter an entirely reimagined Australian collection. First, though, a lot the art — by men, anyway — will be coming down to make space for Know My Name, a celebration of female artists that will dominate this year. Then comes the rehang, and Mitzevich wants to prepare visitors for a sweeping rethink of what it is that a gallery can and should do.

Mitzevich has history here. Before Canberra, he ran the Art Gallery of South Australia for eight years. He sparked plenty of debate in Adelaide with a dramatic reimaginging of the European art collection, a thematic rehang that famously included two headless horses hanging from the ceiling. In Canberra, the director says the new display will be neither entirely chronological nor entirely thematic. “I’m having a bet both ways. You don’t have to be one or the other,” he says. “With this project in Australian art we’ve done both. Parts are chronological and parts are thematic, and we weave it all in together. In some ways, it’s a hybrid.”

Mitzevich wants to use the permanent collection in an “exhibition style”. By that he means there still will be permanent displays, but ones that will be presented more like temporary exhibitions instead of static, immovable arrangements of work.

“I don’t think I need to have the same methodology all the way through,” he says. “What’s important is that we show that art has so many different facets and it’s about trying to share with the audience in a logical, methodical way that art-making has a complexity and it’s much more interesting than art textbooks.”

Traditionalists may grumble — and they certainly did in Adelaide — but Mitzevich is in good company when it comes to gallery trends worldwide. Curators are rethinking their approach at the Tate in London, while at the city’s National Portrait Gallery director Nicholas Cullinan is embarking on a “comprehensive top-to-bottom rehang” that embraces uncomfortable questions about the work on the walls.

Two NGA staff members have also travelled to New York to see the much-discussed new hang at the Museum of Modern Art, where director Glenn Lowry has overseen fresh juxtapositions within a once familiar display.

“We’re really interested in what’s happening there and we’re really interested in what the Tate have been doing in their displays,” Mitzevich says. “We’re all trying to be responsive to the developments in both art and art practice and art theory. These institutions are all pointing in the same direction. The difference is that we’re responding to our collections in a direct way. That’s the nuance that each of us bring. All of our collections are different.”

As with Belonging, curators are being encouraged to work across departments as the rehang takes shape. Mitzevich argues that classifications exist to manage a collection, but those divisions shouldn’t necessarily be reflected on the walls since they “limit the audience’s appreciation” of the work as a whole. “Bringing curatorial groups together that have specialisations in particular areas and asking them to collaborate to tell the story of art history for me is a big step for the institution,” he says. “It’s important that we look at multiple points of view through history and art.”

An 1857 watercolour by Conrad Martens hangs beside a 2008 bark by Nyapanyapa Yunupingu. A few steps away Tom Roberts shares space with Anatjari Tjampitjinpa and other Papunya artists from the early 1970s. Arthur Streeton is paired up with Micky of Ulladulla, an Aboriginal artist whose work also dates back to the late 19th century.