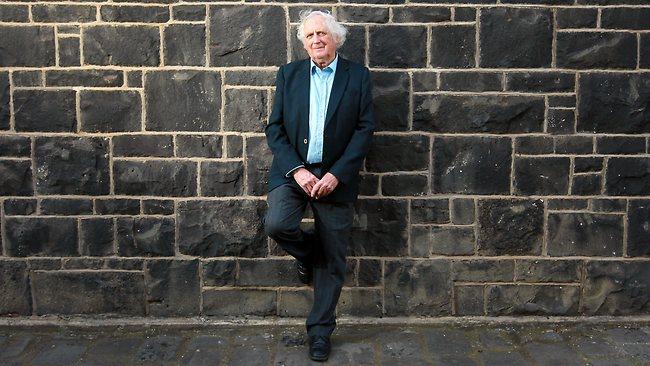

Gadfly Geoffrey Blainey comes to praise Christianity, not to bury it

THE historian finds many positives in the bedrock religion of Western civilisation.

AUSTRALIA'S most prolific historian, Geoffrey Blainey, is about to add another 170,000 words to his account of human history.

At 81, he has been a witness to more than one-third of the European settlement period and has been chronicling Australia's progressions and reversals since his first work, The Peaks of Lyell, was published in 1954. Some 36 books later (Blainey is not sure, it could be 37), he trespasses once again on contentious ground in A Short History of Christianity.

"I don't think I want any more controversy at my age," he tells Inquirer. "But when people started asking what I was writing I was astonished at the vehemence."

Arguably, the renewed antagonism towards religion stems in part from the events of September 11, 2001, the atrocities that drove Blainey to inquire more deeply into the history of a religion that "shaped and misshaped much in the modern world".

"When September 11 happened, people started to look at their own civilisations and rival civilisations," he says. "In some ways Christianity has been at the core of Western civilisation, but we know less and less about it. Including me."

Blainey applies the test of an empirical historian before concluding that, by the standards of the first century AD, the voluminous accounts of Jesus' life count as reasonable documentary evidence. Jesus did exist. He hedges his bets on the resurrection, giving ample voice to its sceptics, but notes that Christ's virtual presence in the minds of his disciples gave Christianity an edge over older, less dynamic competitors. Christianity gained added impetus from its two principal partners, Judaism and colonialism, as it leapt from synagogue to synagogue and was carried on the ships of imperial adventurers.

Compared to most of religion's contemporary critics, Blainey has the advantage of historical perspective that allows him to treat dogma as a passing phase rather than an impenetrable barrier to reason. He notes that science has been dancing with Christianity, at times as a partner and at others as rival, since the Reformation. Declarations of victory by secularist forces have, to date, been premature. He acknowledges, however, the territorial gains made by science and, more recently, by technology, "science's kid brother".

"The exploration of space is astonishing, but in a sense science is staking its own home ground," he says. "It's staking areas that are measurable . . . as difficult as it is, it is the easy ground. The difficult thing is when you're dealing with human beings, activities and beliefs that are not easily discoverable and that may not be scientifically measurable."

Blainey retains the rhetorical good manners of another, more courteous, age in which pluralism and debate were encouraged. In conversation, he qualifies his conclusions with phrases such as "in my opinion" and "others may disagree", granting his interlocutors licence to dispute. He acknowledges some things are unknown, others unknowable, and that some philosophical points are too complicated "for me or anybody" to understand. Yet he invites controversy by rejecting intellectual fashion, just as he has done since the early 1980s when his observations on large-scale Asian immigration earned him the disdain of the academic establishment. It mattered not that his warnings focused narrowly on middle Australia's cultural resistance to large-scale migration.

A decade later, his Stolen Generations scepticism again marked him as an intellectual troublemaker, despite his genuinely held doubts at the weakness of black-armband evidence. He had marched out of step with orthodoxy and was guilty of profanity.

"The Stolen Generation, as it's described, and a loose usage of the word genocide, seem to me to be using the imagination far more than you should," he says. "I think intellectual fashions have been more powerful in the last 20 or 30 years. Big sections of Australians who are in academic life have from time to time had something important to say and most of them don't say it. It's often that if they say something that's unfashionable, their career may not go as far as it should."

Many of Blainey's quarrels with contemporary academe boil down to questions about the nature and jurisdiction of science. Blainey's instinct that science is a process of discovery rather than a body of consensual knowledge, true beyond question, would have been unremarkable 20 years ago. Yet in today's heated climate, he risks being pinned with the badge of the denier, or at very least the arrogant slur of youth that, perhaps, he is simply past it. The rigidity of modern thought struggles with the wisdom of experience, particularly in Blainey's case, where wisdom has been honed by more than a half-century of historical study.

"It seems to me," Blainey advances with customary caution, "It seems to me that science, in the eyes of its spokesmen, has reached an unusual stage. Sometimes in public debates you hear scientists saying this is simply a question for scientists, keep out. We have that in Australia on topics like global warming.

"I think maybe we've reached an unusual stage in the flow of ideas where the science is too much on top. The interesting thing to me about science is it's given the benefit of the doubt now in ways that Christianity used to be given the benefit of the doubt.

"In 1970 the overwhelming majority of scientists believed that there was not going to be global warming over the next 40 years. Suddenly they change their minds and say: this is wonderful, look what science has discovered. They never say, look how wrong science was 20 years ago when they were telling us a completely opposite version. I think science is riding more highly than at any previous moment.

"So few of us are scientists that we don't realise that it's just like any other intellectual discipline and it stumbles. And has great achievements, but waits for the achievements for too long."

His concern for the intellectual climate, however, does not drive him towards cultural pessimism or dissuade him from his view that modern life, particularly in Australia, is immeasurably better than it was in his youth. Blainey retains qualified faith in the Whiggish view that holds that innate creativity and our better instincts propel us ever higher on the eternal journey of progress.

"I'm Whiggish in the material sense, I think science and technology have transformed large parts of the world," he says. "We expect to live much longer, to have much better health, to have enough to eat, to be able to travel and see the world. I'm Whiggish in the sense that we've had astonishing changes materially over the last 200 years.

"But I think human nature has got in it wonderful potential, but also terrible potential. We saw that in Hitler, in Stalin in his worst days, and in Chairman Mao. What human nature is like, and how we erect a society where we cope with the bad in human nature and encourage the good, that really is a much more important issue than exploring in outer space."

Blainey, whose account of Australia's struggle against "the tyranny of distance" is an enduring part of the national narrative, is confident about the continent's future. He accuses historians of drinking from half-empty glasses.

"I myself think that Australia in many ways is one of the great success stories in human history," he says. "Terrible things have happened, there have been all kinds of faults. But the fact that in face of great difficulties 22 million people are living here, nearly all of them with a high standard of living, the standard of living that only the prosperous would have had in the Western world 100 years ago, I think that's a great achievement.

"I think that while we've done great damage to the environment, we haven't done as much damage as people say. And while relations with the Aboriginals in many ways were deplorable, you have to ask yourself what would you have done in 1788? Would you have said no, we must leave the Aborigines on their own, and no member of the outside world must come there?

"I just think the relations between Europeans and the Aborigines is one of the most difficult confrontations in all human history because their cultures are just so different and almost so un-meetable. That's the tragedy of human history. And we keep saying we must blame people for everything. A lot of things in history, you don't get very far by blaming people because the problems were there from the start."

Blainey's practised objectivism, maintained with admirable discipline for 550 pages, leaves the reader guessing about his personal faith. When asked, he talks about his Methodist childhood, and acknowledges that one of the book's indulgences might be an excessive enthusiasm for Methodism's founder, John Wesley, and his rousing hymns. He is not, however, a member of a congregation, nor does A Short History of Christianity read like an application for posthumous admission to the ranks of the heavenly choir.

"Part of me is religious, I suppose," he allows, in a moment of uncharacteristic public self-reflection. "When I go to church or go to a funeral or something I find the words and traditions of the civilisation I belong to moving, although I don't obey the precepts as much as we probably should."

His next project is a shorter version of the book, abridged for the benefit of translators, who insist on a volume half the size. His Short History of the World was a surprising hit in Portuguese, he tells Inquirer, where it made the nonfiction bestseller list.

In short or extended form, however, A Short History of Christianity is a story without an ending. It is not, as Blainey's cultural opponents might have hoped, Christianity's obituary.